After the wide and relatively busy Alaska Highway from Whitehorse to Watson Lake, we were looking forward to the Stewart – Cassiar Highway, a much quieter road that would be our route through northern British Columbia. A string of small settlements provided the occasional hot meal and chance for resupply and added a good dose of First Nations and European history to our experience of Canada. Our wildlife sightings took a step up too: we’d been warned of plentiful bears on the highway, so made sure we bought a second cannister of bear spray at Watson Lake, just in case.

From Watson Lake we backtracked 20 kilometres of the Alaska Highway to the junction marking the start of our route south down the Stewart – Cassiar Highway. This character church opposite a roadhouse at Upper Liard had caught my eye on the ride in.

14km from Watson Lake we spotted a very slow moving, stooped form on a bicycle, and Hana recognised it to be a fellow she’d seen walking his bike through town about 4pm the previous afternoon.

Alfred told us he’d been on the move all night – mostly slowly scooting his heavily draped bike, with only one shoe – due to two nearly flat tyres. We chatted for a while and learned that he was aiming for Whitehorse, several hundred kilometres NW, where he hoped to ‘sort his bike out’. Alfred was very chatty and full of ambitious and somewhat eccentric ideas that he shared with us, but it was hard not to feel sorry for this old man attempting to make an existence from trash and found objects from the roadside. After 15 minutes of chatter we gave him some food and water and rode on our way, turning occasionally to see him shrink into the distance.

Once on the Stewart Cassiar the road narrowed significantly and traffic became no more than occasional – about as good as sealed highway touring gets. The forest remained predominantly spruce, as it has done for most of our ride south from the Arctic Circle, but for much of the way to Boya Lake it was scorched by forest fires. If causes for such fires are natural, they are monitored (for public and infrastructure safety) rather than fought, as fires are integral to the natural cycle of these forests: seeds are released by heat, and the forest thins, preventing larger fires in the future.

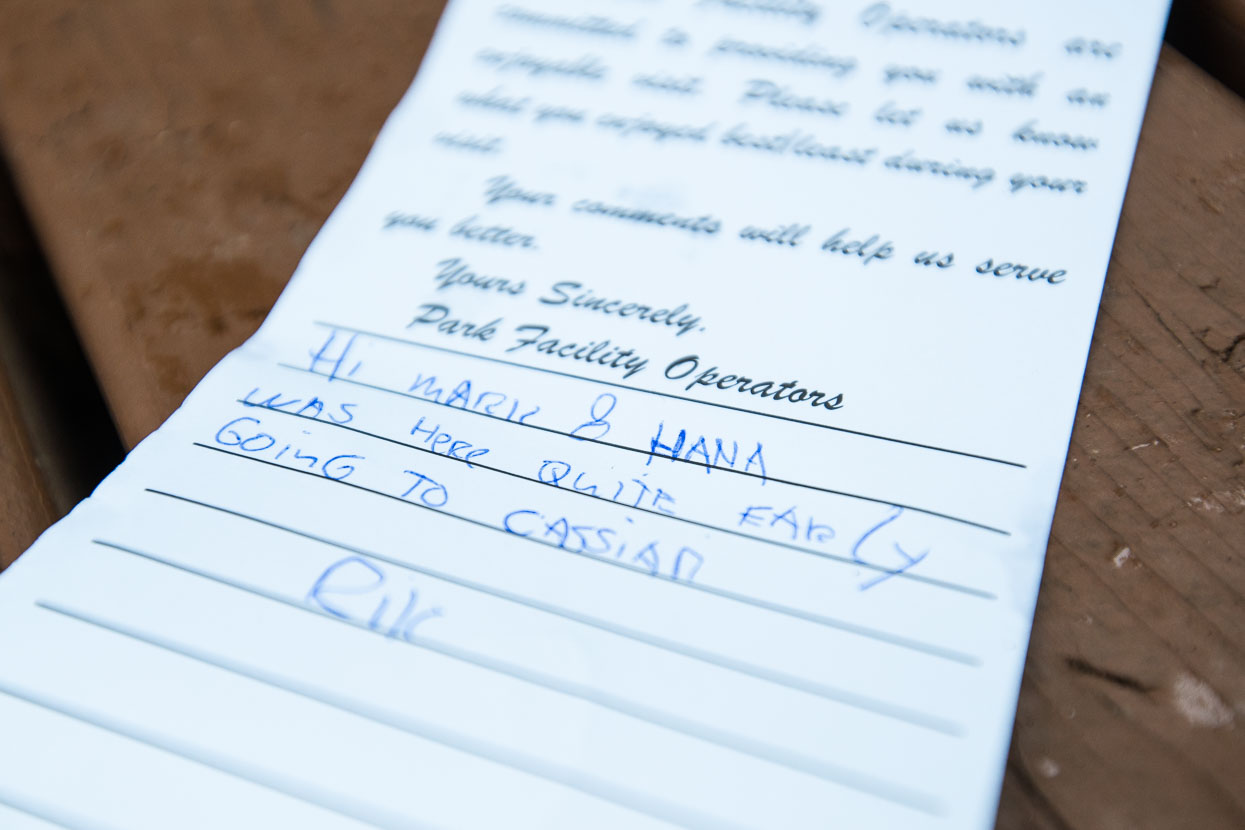

We arrived at Boya Lake to find a note from Rik, who we had ridden on and off with much of the way from Deadhorse, but had agreed to part ways with at Watson Lake, for a bit more time on our own. We caught up at a cafe at Bell II a few days later and had a chance to share bear stories.

The Boya Lake campground, our first overnight stop on the Stewart Cassiar, made a great stop. The lake’s shallow water – fed from streams draining limestone ranges – was incredibly clear and a beautiful colour, even under the grey skies that were forecast for the following days.

Boya Lake.

From Boya onwards the road climbed gradually towards Cassiar, an area with a long history of Jade mining.

The irresistable offer of free coffee drew us into the local jade store, where the staff kindly let us eat our lunch inside, out of the cold headwind that had picked up.

Lakes are a constant feature of the Stewart – Cassiar route – offering many moods and making sites for camping, townships and recreation.

As the road wound its way south the mountains drew closer and taller. After weeks of either distant ranges, or benign rolling country it was nice to be among steep country and fast moving rivers again.

About half of our nights on the road are spent at official campsites; sometimes commercial, but more often state run of some kind – the most basic being free, but offering pit toilets and picnic tables, like this one at Sawmill Point, Dease Lake. Paid state camp grounds usually have a potable water supply as well and bear lockers for food storage. Most of the rest of the time we free camp at rest areas, gravel laybys or wherever we can find a relatively quiet spot.

Crossing the Stikine River Bridge. From Sawmill Point on Dease Lake through to Iskut we had a day of persistent rain and lots of up and down through some scenic country, unfortunately the camera stayed in the bag for much of it.

The rain stopped late in the day shortly before Iskut, where we found a commercial campground for the night.

Consulting the map and guidebook for camping beta alongside the Burrage River. We’re still using Milepost for info about possible campsites, water collection and food stops, and run both Back Country Navigator and OSMand for navigation on our Samsung S5 phones.

On this evening we’d collected water from a river for the evening camp, but struggled to find a decent site. Eventually we turned off down a clearly private road to try and poach a campsite in the forest. There had been no dwellings for hours and we were sure there was nobody about. A short distance into the forest we found the remains of a First Nations ‘replica’ camp and settled in for the night.

Dinner along the Stewart Cassiar were a mixture of freeze-dri and food we could forage from the limited selection in local shops.

We’d been warned off camping in this general area as it’s known for being a gigantic blueberry patch, so we remained on high alert for bears and ate and hung food well away from camp.

Crossing a stream on the edge of the Ningunsaw Ecological Reserve.

Beyond Bob Quinn Lake the mountains steepened further and we passed many avalanche warnings.

It’s along this section of highway that we started to have regular bear sightings. We’d seen a mother and cub back on the Alaska Highway, but that had been our sole encounter until the Stewart Cassiar, the southern section of which has a repuation for bears. We spotted one grizzly (I’d nearly ridden too close while scoping for a camp spot in a rest area), and then began to see black bears fairly often – totalling about 10 by the time we completed this section. This particular bear was persistent and unafraid of us, or vehicles and we had to wait some time for a chance to pass, hiding behind a truck, while the bear lingered on the road verge.

We found some lunch in Meziadin before turning off down the mountain road towards Stewart. On a road like the Stewart Cassiar, and like much of the rest of our travels through Alaska and Canada so far, any kind of sit down meal is a much anticipated treat.

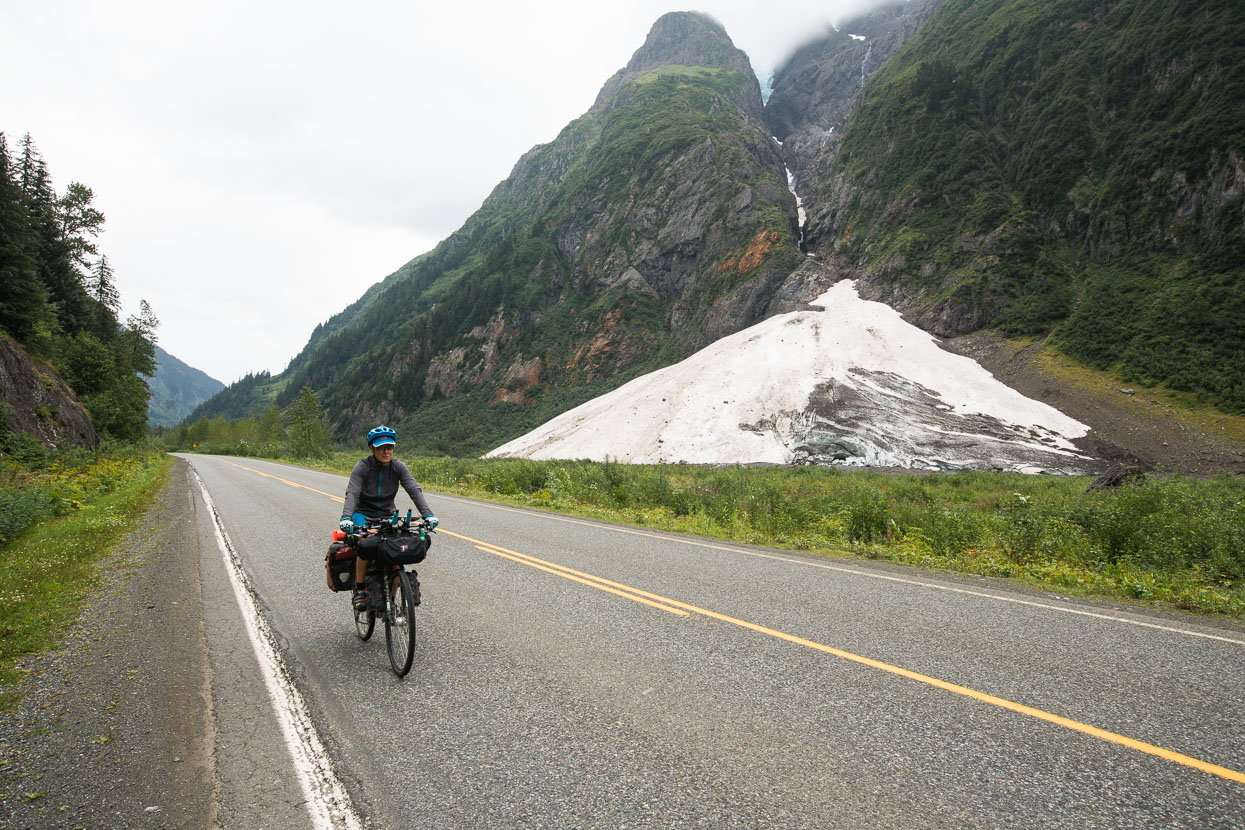

At Meziadin we departed from the Stewart Cassiar highway to make a detour to the townships of Stewart and Hyder, at sea level. It would be the first time we’d been back to sea level in two months – since departing from the Arctic Ocean at Deadhorse. A mountain road, squeezed deep between peaks of BC’s Coast Range wound its way between glaciers and down ever thickening forest towards the coast.

The snouts of glaciers – fed by out-of-sight neves – come close to the highway.

The Bear Glacier is the most well known of those passed en-route to Stewart. Up until the 1940s the glacier reached the road, where Hana stands.

Avalanche debris from distant slopes lasts well into the summer.

Looking upstream along the Bear River. During the ride down valley we saw the biggest change in forest type we’d experienced on the ride, as the drier, high elevation spruce changed to taller, denser coastal forest with thick undergrowth – an indicator of the high levels of rainfall this mountainous coastal environment receives.

At the end of the road, just a stones throw from the estuarine waters of the Portland Canal (actually a fiord), lay the township of Stewart. We instantly liked this quirky, remote town. Dated buildings, a frontier flavour and mountain atmosphere give the place a unique feel. High above the town fingers of the massive Cambria Icefield are visible, hanging between the peaks.

We spent three nights in the municipal campground, pretty much right in town and made good use of the restaurant and wifi at the King Edward Hotel. The endless coffee refills kept us going too!

A couple of small grocery stores sorted us for resupply.

Stewart and the Portland Canal form the most northern ice-free port in Alaska. Essential for the shipping of ore from nearby mines in Hyder and the transport of logs.

The deep fiord and steep mountainsides remind us of Fiordland back home in NZ. The ride in and general location has many parallels with New Zealand’s Milford Highway.

Stewart lies at the head of the Portland Canal, a deep fiord that penetrates 210 kilometres in to North America’s Coast Mountains. The canal forms the border between Canada and Alaska, to the north.

Looking back from the port at Hyder, towards Stewart and the Bear River valley.

Just a few kilometres round the harbour from Stewart it’s possible to enter the township of Hyder, in Alaska. There is a Canada controlled border post here, but entry into Hyder is unmonitored and casual. You do need your passport to come back though. We biked through Hyder twice, while heading up valley in hope of seeing bears fishing for salmon.

Hyder’s population is tiny and most of the buildings on the main street seemed to be abandoned.

View from the road up valley behind Hyder, along the way to Fish Creek.

In this part of the world it’s salmon spawning season. Mature fish head upstream from the ocean to the shallows of Fish Creek to spawn and then die. Many of them also become bear food. This particular site is a US Forest Service observation site, where the public can watch grizzlies and black bears catch and eat salmon. Bear activity is closely monitored and charted through the season.

We visited twice in the evenings and got lucky the second visit. Watching this grizzly bear saunter casually through this pond in the drizzle, and then swim towards Fish Creek as the water deepened was a truly primal sight.

The large grizzly (a regular visitor) then entered the creek and began fishing. Panicked salmon churned the water into a splashing froth but somehow not all could escape the massive claws and fast swipe of this beast.

A second bear entered the creek after the first disappeared into the forest.

Claws at the ready…

… to dismember his catch.

Returning along the coast from Hyder to Stewart; the lichen draped trees an indicator of this damp coastal enviroment. The humidity here took a bit of getting used to after the high and dry country we’d been experiencing.

Satisfied with our bear viewings we hit the road again for a final couple of days on the Stewart Cassiar Highway, en route to the Yellowhead Highway.

First night out of Stewart we camped at Bonus Lake.

First Nations communities feature often along the Stewart Cassiar, but not more so than at Kitwancool and Kitwanga where native totems are on display.

At Kitwanga an old fortified site can be visited.

A run down church at Kitwanga, the second totem site we visited.

Village of Kitwanga.

The Nuts & Bolts

⊕ The Stewart – Cassiar Highway (connecting the Alaska and Yellowhead Highways)

⊕ 874 kilometres

⊕ A highly recommended touring route: traffic is light and mostly tourist traffic. There are enough small towns for comfortable resupply and occasional dining treats. The terrain is changable, diverse and pretty much continually interesting. Biking the highway you witness changing forest types as the northern spruce gives way to a wider range of species.

⊕ The detour to Stewart/Hyder is well worthwhile. We rode in and tried to hitch out, but gave up after 2 hours and then rode 30km, getting a ride further up valley by asking a driver.

⊕ Refer to The Milepost for more information.

Thanks to Biomaxa and Revelate Designs for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Fantastic post!

Thanks!

Nice Bear Pics (Y)

cheers Rik – we got lucky! Have seen none in USA – despite riding through the area that has the biggest concentration of grizzlies in North America …

Have seen some skunks though, and hundreds of deer.