iskanwaya ruins, the long way

Time and time again on this 39,000 km journey we’ve found the richest experiences in the areas we knew the least about: where we’ve had to plan our own route and logistics and pedal, to some extent, into the unknown. Once you’ve had a taste of this sort of bicycle travel a hunger for it remains. We sated ourselves with our Apolobamba adventure, but of course that ultimately only left us wanting more…

This post brings our Bolivian adventures so far up to date, continuing from Charazani, where we’d based ourselves for our Apolobamba loop through to Sorata, a small, sleepy mountain town near the foot of the Cordillera Real. Sorata’s the start/finish town (depending on direction) for both the Tres Cordilleras and Mama Coca bikepacking routes.

We discussed at length our possible options for our route to Sorata. One option was to rejoin the Tres Cordilleras immediately back up on the puna and follow that to its conclusion in Sorata, while another was to explore the mountains between Charazani and the Rio Llica canyon, and the canyon region itself. The Rio Llica is one of many east Andean tributaries that merge to form the great Amazon river, the Beni and is one of the biggest Bolivian canyons to sever the Andes between the puna and the Amazon. From the river we’d climb out and rejoin the Tres Cordilleras route near Sorata and the northern end of the Cordillera Real, where we planned to explore the range a little and pick up the Mama Coca route.

In the end we opted for the latter; we’d done our puna time riding down from Cusco and decided the Rio Llica canyon option would serve us up quite a bit more variety with its dramatic changes in elevation: from as high as 4700m right down to 1800m, and it was an area we knew nothing about, which to our novelty seeking tendencies, made it all the more tempting.

We hadn’t climbed far out of the Charazani valley before the views opened up and we could look back at the village of Curva, perched on its steep spur, and the full glory of the Cordillera Apolobamba. The view made up for the mist-swallowed final day and a half we had coming out of the range.

This region was colonised by smaller civilisations long before the Inca became top dogs and evidence of their occupation was widespread, in the form of stone terracing, the remains of round houses, pathways and retaining walls.

Our first stop out of Charazani was Amarete, which several people in Charazani had told us was ‘bigger’ and that it had a mobile data signal, which Charazani doesn’t. So we’d put in a relatively short day, planning to stop there and use the internet to catch up on some admin and planning. While Amarete might have been bigger, and indeed had 4G, we discovered that in Bolivia ‘bigger’ does not necessarily equal ‘more stuff to buy’.

In fact, remote little Amarete was like a window back in time 100 years, with its rammed earth and mud brick buildings, rumpled streets and its lack of motorised transport. The local people take advantage of the pre-Inca terracing and roads that lattice the surrounding mountainsides to cultivate potatoes and grain, and seemed to almost exclusively use traditional animal-means to do so.

Instead of motorbikes, tractors and trucks, the streets of Amarete were alive with the clopping of mule and donkey hooves and the soothing baaaaing of small flocks of sheep.

We’d arrived in town hoping to find a better range of restaurants than we’d seen in Charazani, but it turned out there was only one, and it was only open in the evening. Instead, we sat in the plaza and amid shy glances from the locals, ate crackers and tuna that we picked from the shelves of a spartan dirt-floored tienda. The elder menfolk all customarily shook our hands and went back to their soporific afternoon in the sun.

As we finished lunch another older man came and introduced himself as Teofilo, and asked if we needed somewhere to sleep. Teofilo was the custodian of the municipal building, which like most in this part of the world, had a couple of rooms devoted to housing town guests, for a small price. We were given a room, shown where the water was and a place to leave our bikes. A good host, Teofilo was also eager to hear all about our plans, to the extent that he wanted us to draw him a map of our intended route across to Sorata. He was a lovely guy and wanted to make sure we knew what was coming up and that we were prepared.

Teofilo alerted the woman who ran the village restaurant that there were a couple of gringos in town and that she should prepare us some dinner, and meanwhile we walked with Teofilo as he went to feed his pigs.

All of the men in the village wore hats similar to the one Teofilo has in the photo above, with different colours and designs denoting seniority or responsibility.

Later, back at the municipal building, Teofilo insisted on having his photo taken in his traditional dress. He was extremely proud to host us and make sure we were taken care of.

A long day of climbing followed the next day, first passing small villages until we reached the quieter heights of the puna.

Already Amarete was a pleasant memory, out of sight in the steep valley below, while the Apolobamba towered above.

Hard earned views, but we were glad of the route choice.

We rode two main passes that day, the first at 4758m and the second at 4605m, the latter of which we stopped at not long before dark to camp on. A solitary decaying ruin, probably hundreds of years old, gave us some shelter from the wind. Apart from a distant dog’s bark, we had the entire upper valley to ourselves.

The pass positioned us on the edge of the impressively deep Llica Canyon, with a perfect view across to our distant objective: the Cordillera Real. Somewhere in the shadowy folds just below the cloud lay the town of Sorata; proximate, but ever so far away all at the same time.

A temping dirt road snaked down the mountainside towards the canyon, but we’d chosen a more circuitous option, that would drop us into a different section before a long climb back out to join the Tres Cordilleras route on the puna.

An abandoned road led us up over a small saddle, with an amazing view across to the Cordillera Real and across the puna. We could even see the slightest blue sliver of the waters of Lake Titicaca on the horizon.

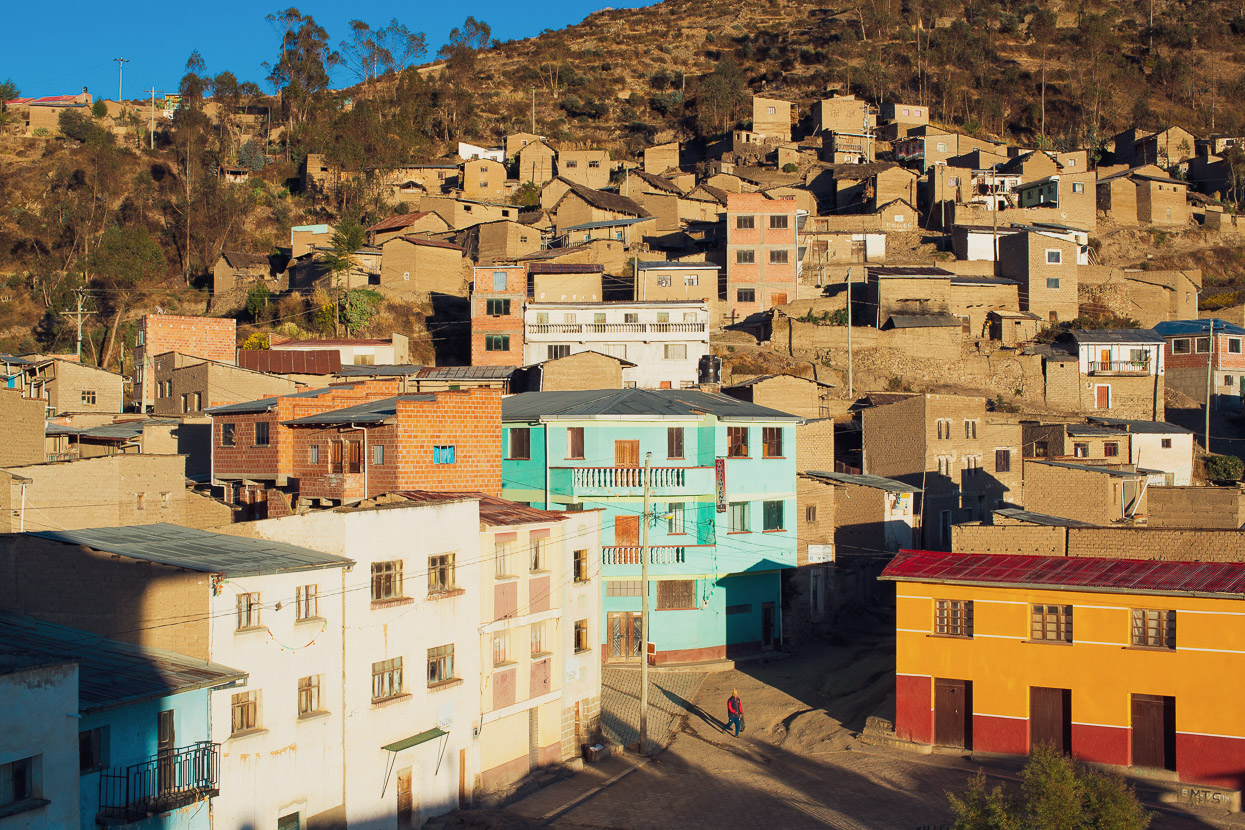

The road descended 2000 vertical metres, from the dry and rocky alpine basins and ridgetops down to much more fertile surroundings at Chuma, a reasonably big agricultural town. Of course the Sunday market was in full swing as we rattled over the cobbles into the plaza and literally the whole town stopped what they were doing and stared at us. It’s rare that we feel self conscious in other cultures territory these days, but this was definitely one of those moments. It was as if aliens had just landed. Eventually a couple of older men came and shook our hands, breaking the ice. We took refuge inside a quiet restaurant to eat lunch and then explored shop after shop, trying to resupply with half decent food.

As we repacked the bikes another older man, from out of town, came to talk with us. He knew the area very well, having been a guide in the past, and in the course of our rambling conversation he mentioned some interesting sounding pre-Inca ruins further down the canyon – away from our planned route, but of course sowing a seed of curiosity in our minds.

A steady afternoon of riding followed as we wound our way around the side of the canyon towards our final descent. In one small village we stopped for a soft drink, but were soon invited by the family who owned the tienda to eat maize, rice and eggs. They were a very nice family and several members of the extended family even came over to meet us too, hugging us warmly and pecking us on the cheeks. Such invites have been very rare in South America, so it was nice to have the contact, especially after the intensity of our stop in Chuma.

The seed the old man had planted sprang into a seedling in my mind that afternoon as we rode a final steep climb up to a junction on the sidle road. From there we planned to make a long descent to the canyon and back out to join the Tres Cordilleras route. Instead we sat in the sunshine of a warm afternoon at 3200m, gazing across at the shimmering massif of Illampu and the rest of the Cordillera Real and discussed our options. The detour to the ruins sounded worthwhile, but it would mean a longer route to Sorata and an even deeper plunge into the canyon – right down to 1100m, which would mean a monumental climb back out. But the will to explore this interesting region further was there so we decided to go for it.

We camped near the road that night, hidden by a field of scrub. This section of the canyon is relatively populated, with lots of small villages and hamlets that probably have roots back to pre-colonial times. They seemed to be having a Bolivian version of Battle of the Bands, but remotely, as we could hear rhythmic drum beats and trumpet blows emanating from at least three different pueblos, possibly the buildup to Bolivia’s independence day celebrations.

We picked up some food in Ayata and then followed a series of dirt roads and double tracks east along the canyon wall towards Aucapata, the closest town to the ruins. We discovered one road that was not on the maps yet (or satellite) which saved us a bit of climbing as we passed through Vitocota, Totorani and Sayhuani and then onto Aucapata.

We could hear distant drumming much of the day, and the school band was out for practise as we passed through Sayhuani. Brass bands are big part of the culture in this country and feature in virtually every important civic event.

The sun was just leaving Aucapata as we made the final descent into town after an incredible day of quiet, dirt road riding.

Aucapata’s a pleasant, sleepy little spot with a classic colonial-style plaza surrounded by two-story stone buildings, built with locally quarried rock. It’s a living museum in many ways. There were three or four basic cocinas to choose from, all serving a single-dish option for lunch or dinner and catering to gold miners from camps lower in the canyon, archaeology teams from Iskanwaya, and the (very) occasional tourist.

Like most towns we’ve visited in Bolivia so far, it seemed as if half of Aucapata’s population had left in hope of better opportunities for work and education in La Paz, so consequently it felt much like a ghost town.

We found a bed for the night in a hostal that, like so many buildings here, was still under construction. It was the sort of the place where the bedding is never changed and the single shared bathroom never cleaned. But we’re used to that now.

The following afternoon we made the 11km walk down to the Iskanwaya ruins, which lie about 250m above the canyon floor. The site is quite hidden and no doubt its location was chosen especially for this reason by its founders, the Mollo people. The walk down was interesting in itself as we descended into the ultra arid lower canyon slopes. Dominated by thorn bushes and cactus it was a stark contrast to the grassy alpine valleys above.

Jaguar worshippers, the Mollo people were a post Tiwanaku culture (roughly 1000–1500 AD) that pre-dated the Inca Empire. It’s theorised that the Iskanwaya were probably conquered by the Inca at some stage and the Mollo people, along with many other cultures of the time, were assimilated into the empire. The Kallawaya healers, whose culture has prevailed until modern times are thought to be direct descendants of the Mollo.

There are the remains of over 100 buildings at Iskanwaya and it’s thought that it supported a population of roughly 2500–3000 people. I think that’s an impressive achievement, considering the inhospitable environment in which they lived – with scarcity of water, agriculture and suitable land. But somehow they made it liveable by installing an intricate system of aqueducts to grow crops and sustain their population.

These days the site is an active archaeology project and much of it is undergoing new digs to broaden knowledge of the Mollo culture.

There’s a small museum in the town itself. It was extremely lacking in any sort of interpretation, but the storage rooms were very impressive, containing hundreds of items of complete pottery, grinding and cutting tools and pottery fragments. A huge amount of artefacts have been recovered in the region.

Seeing this stuff brought the ruins to life in our imaginations and made them less abstract by adding a much more human perspective.

It turned out we weren’t the only gringos in town when we caught sight of a big Unimog overlander vehicle in the plaza the following morning. The owners were Canadian Swiss couple Pierre and Theresa who have been travelling all over the world in their custom fitted Unimog for several years. What began as a quick hello turned into a whole afternoon spent in their company, drinking coffee and sharing travel stories. We must have had good stories because we were invited back for dinner, which was not only an absolute treat for the company, but Theresa is a very skilled cook, so we ate like kings. Pierre travelled solo through parts of South America as a young man back in 1977 and still has his original diaries so it was fun to hear some of his anecdotes from 42 years ago.

Thanks Pierre and Theresa if you read this and good luck for the rest of your time on the road.

After two days in Aucapata it was time to move on. The canyon was spectacular in the early morning light; ancient and mysterious. We followed an undulating road along its wall before making a huge descent down to Pallayunga on the canyon floor.

All of a sudden it was 27 degrees and a hot, dry wind blew dust off the road as we pedalled into town. Small stalls sold banana, papaya, mango and other treasures from the jungle, readily available here down at 1100m and so close to the Amazon. The town lies on a strategic trade route and it’s actually possible to ride out to the Amazon from here, turn south and join roads leading up to La Paz, back on the altiplano. We were headed there too, but via Sorata and ahead of us was a 2000m climb to get back out of the canyon. We ate lunch in the village cocina, loaded up with a few litres of water each and hit the climb.

The next few hours went by a haze of road dust and sweat and we stopped for the day just on dusk, having made a 1600m dent in the elevation difference. Not bad for an afternoon’s work.

We camped with a grandstand view of the canyon and in the morning continued upward. In places the road was crudely hewn into the cliffside and supported with retaining walls of quarried blocks. Safe on a bike, but a spooky drive no doubt.

It was the first day of celebrations for Bolivia’s independence day (officially August 6) and as we passed through one town their drum-beat led procession was in full swing, with everyone out in their best clothes and the kids dressed up as soldiers, nurses or in traditional dress. It was all quite entertaining and we had to resist several offers to join in as we wanted to get some more miles down.

The options for ride snacks haven’t improved, It’s hard to find anything other than cheap chocolate bars and heavily processed junk food. Even simple foods like bananas, peanuts and raisins are very hard (usually impossible) to find in the mountain villages.

In the afternoon we turned away from the main canyon and began climbing up a side valley towards Sorata. The landscape through this area is quite spectacular as we began to approach the shadow of the Cordillera Real.

And finally, after another half day of riding Sorata itself came into view, scattered over a mountain slope at a civilised altitude of 2700m. That’s the Cordillera Real in the background.

It was good to arrive in Sorata. Our biggest town in weeks. There was food in abundance: cake, pizza, classic Bolivian dishes and all the fruit we’d missed. The air was warm.

We found a room in a hostal right on the plaza with a room for NZ$15. That’s our room with the open door off the little balcony on the second floor. Great for kicking back and watching town life go by.

Of course it wasn’t peaceful for long. For some reason Sorata celebrates its independence day a couple of days later, and runs the fiesta over three days. So town came alive with the incessant beating of drums, parades, street parties and general rowdiness. Everyone participates, from the youngest school children through to the most senior of the town.

It was all quite entertaining and much of it based on very old rituals; for example in the evening men from the village would form two or three small circles in the plaza as they beat drums, and played flutes and trumpets standing around temporary shrines made from coca leaves and the odd cigarette offering. All the while getting through crate after crate of beer.

There’s some pretty good trail riding in Sorata. Better suited to suspension bikes, but definitely still enjoyable on our Otso Voyteks with their plump 3 inch tyres. These shots are from Loma Loma, a long single track ride with epic views of the cordillera the whole way down. We rode to the start of this one from town – a 1700-odd metre climb, so we must have been feeling quite fit!

Sorata was the end of the road for us for the time being. We have three family members in varying states of ill health and so after three and a half years on the road it was time to go back to NZ for a family visit to see our fathers who are both unwell (congestive heart failure and bladder cancer) as well as Hana’s sister who is undergoing treatment for breast cancer. There were also a new niece we had not met yet. So after four days in Sorata, we left the bikes in the care of the hostal and travelled to La Paz to fly out to Thailand and New Zealand for four weeks.

As I write this, we’re now back in La Paz, reacclimatising and today will be headed back to Sorata to resume riding on the Illampu trekking route and the Mama Coca which will bring us back to La Paz over about 8 days. It’s been amazing to see everyone, have a break and fatten up a bit, but we’re really looking forward to getting back on the road now!

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful?

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs. Every small donation helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Otso Cycles, Big Agnes, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow.

As far as interest, colour & photography, this has been the best blog ever ! We’re back to bun hats & big bottoms with brass bands thrown in. How wonderful. It is a privilege to travel through BOLIVIA on your handle bars ……I am loving every minute of it. Can’t wait for the next instalment. THank you for the armchair ride & for giving me such pleasure. You have my utmost admiration. GET WELL WISHES FOR YOUR FOLKS.

Thanks Madge, always nice to heard from you and so glad you enjoyed the post! Hope you enjoy the subsequent couple of posts to bring our Bolivia adventures up to date. Bolivia has been amazing so far, most notably the mountain scenery. The food is nothing to write home about though 😉

Hi Guys,

Looks like you did an amazing version of the Tres Cordilleras. Loved the photos around Sorata, it had me looking wistfully at the plaza & the familiar landmarks. It even looked like you stayed in the same Hostal as ourselves, though we later moved further out to Altai Oasis about 3 km out of town, for a bit of peace & quiet. Look forward to the next installment towards La Paz & more of the Cordillera Real.

Cheers

Safe Riding

Peter

Thanks Peter – glad you enjoyed the post. Yes Bolivia got off to a great start in terms of adventure and being off the beaten track. It’s been a lot of fun & a good challenge! I hear you re peace and quiet in Sorata – they sure love to party there. Amazing how much beer they can drink there. We’re now in La Paz and looking forward to more of Mama Coca once Hana heals up.

Cheers Mark + Hana.

Nothing like a good parade. Great story and photos.