Across the Cordillera Blanca.

The story picks up as we leave Tarica, the grubby highway town we’d reached after coming off our high traverse along the Acuán Range. Arriving at Tarica and the narrow paved highway that’s etched into the steep foothills bordering the northern end of the Cordillera Blanca connected us with the Northern Cordillera Blanca bikepacking route.

This route, consisting almost entirely of dirt roads, carried us around the eastern side of the Cordillera. This side of the mountains is much more remote than the west, which is more easily connected to the capital of Lima. The eastern Cordillera was in fact virtually inaccessible to tourists during the years of the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) communist guerrilla group, who controlled the region. But even though this region’s steep valleys are free of the ‘troubles’ of the eighties and early nineties, there is still very much a sense of isolation – and I think a fair measure of poverty – as we follow rough dirt roads, hewn into rocky hillsides, that connect the smallest of villages.

Considering it’s the dry season, the weather has been anything but settled, and a cold rain blew across the open hillsides as we made the long (1000m+) paved climb to the pass of Abra Cahuacona – our first crossing of the Cordillera Blanca divide.

We were quickly chilled on the fast descent and stopped in Pasacancha for lunch and a warm up before continuing on a dirt road that eased its way in and out of the ridges and gullies of the cordillera foothills.

We stopped to chat to this couple who were building a new mud brick home by the side of the road. Just a few days and it would be ready to move into they reckoned. We’ve seen a lot of new looking mudbrick homes throughout this region of Peru. As if there is some rapid population expansion happening, even here in these remote villages.

The bricks are made from a mixture of mud and straw and take three days to cure in the hot sun. There’s a flurry of brick making going on due to the dry season conditions.

People are almost invariably chatty and happy to help out when we ask questions.

It was only mid afternoon when we got to Andaymayo, a village so small there’s not even a street grid shown on the map. But the reception was welcoming and feeling tired from the past few days we decided to stop early. We were soon mobbed by the village’s kids, who told us we were welcome to pitch our tent in the village plaza, just down from the main street.

An entertaining couple of hours followed as the kids asked us every question imaginable. They kept wanting to see the bottom of our shoes to see if they had cleats that clipped to the pedals (they’d obviously seen them on other cyclists). We were told that they’d seen two Brazilian cyclists the day before but no one else had stayed in the village for a year before us.

Soon our tent was filled with several laughing children, while a few other curious folk dropped by to chat with us. We ended the afternoon with a walking tour of the village, the children all fighting to hold our hands while we walked around looking at burros, cows, sheep, various plants and a tepid hot spring that served as the village’s public washing area.

We left friendly Andaymayo early the next morning continuing along the traffic free dirt roads that encircle the east side of the Cordillera. The only traffic we do see is the odd motorbike and occasionally a collectivo (taxi). There’s very little private car ownership.

If there’s an iconic memory I’ll be left with from this part of the ride, it’s mudbrick homes and the sight of maize – the universal food staple of rural latin america – drying on porches.

About 10km before Pomabamba we stopped for a snack and were soon sampling some of the 400 bread rolls that the village was baking for its weekend fiesta.

A furious production line was underway.

And each board-full of dough was walked over the road to the baker, who thrust them into a clay oven. We left with another half dozen, still warm, in a bag for later.

We were due for a rest day and the small town of Pomabamba made a perfect place for it. We found a hotel right on the plaza (this photo is from our third floor room’s window) and settled into some quality resting and eating (ice cream and chicken and chips mostly!). This town seems to have been spared the devastation wrought by earthquakes on the western side of the mountains and has a pleasant plaza surrounded by older, more characterful buildings.

With us both suffering from bad stomachs, or ‘Atahualpa’s Revenge’ as it’s dubbed here, along with mild colds we decided to take a second day.

I think I’ll just sit on the footpath and eat icecream when I retire.

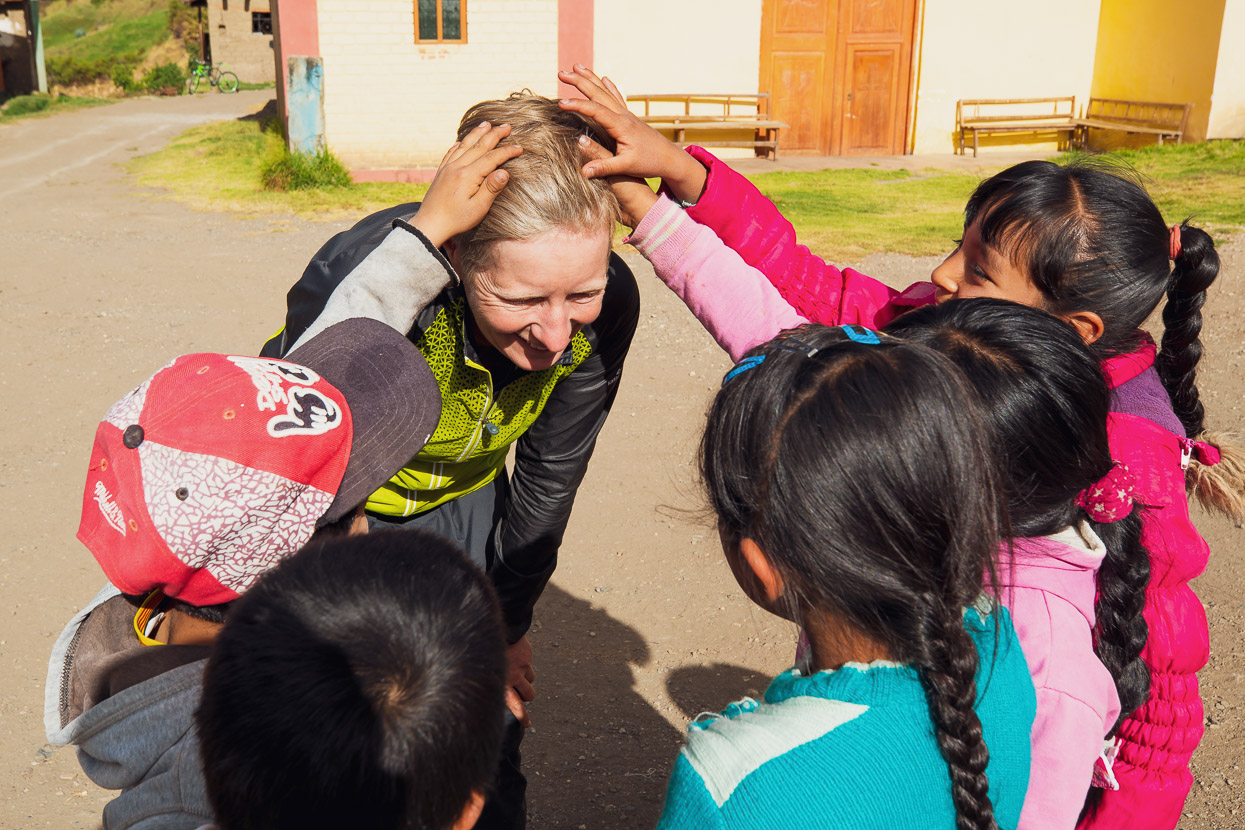

Hana holds court with a group of school kids in Pomabamba. Kids are always full of questions and it’s always a good opportunity to practise our Spanish as kids tend to be easier to understand that rapid-talking adults. They sometimes know a few words of English too that they are eager to try. It’s hilarious how often someone will shout out at us ‘Good Morning’ at the top of their lungs, when it’s the middle of the afternoon.

The ever-quiet roads beyond Pomabamba led us further south along the edge of the Cordillera towards Llumpa, from where we’d begin the long climb towards our crossing of the divide of the Cordillera Blanca. I’d resorted that morning to finally taking an antibiotic to rid myself of the runs for good, but the side effects left me grovelling and resorting to walking my bike on the steepest climbs.

We arrived in Llumpa, checked into a very basic guesthouse, and I was asleep in moments.

We left at 7am the following morning, warm light already bathing the town and hillsides and dropped down into the Rio Yurma canyon.

We wound our way down the dusty road and into an arid land of cactus and thorny shrubs. The geology ever impressive. From the low point of 2400 metres a 2300 metre climb back out to the Portachuelo de Llanganuco pass awaited us. We aimed to tackle 2000 metres of it that day to a high camp on the east side of the pass.

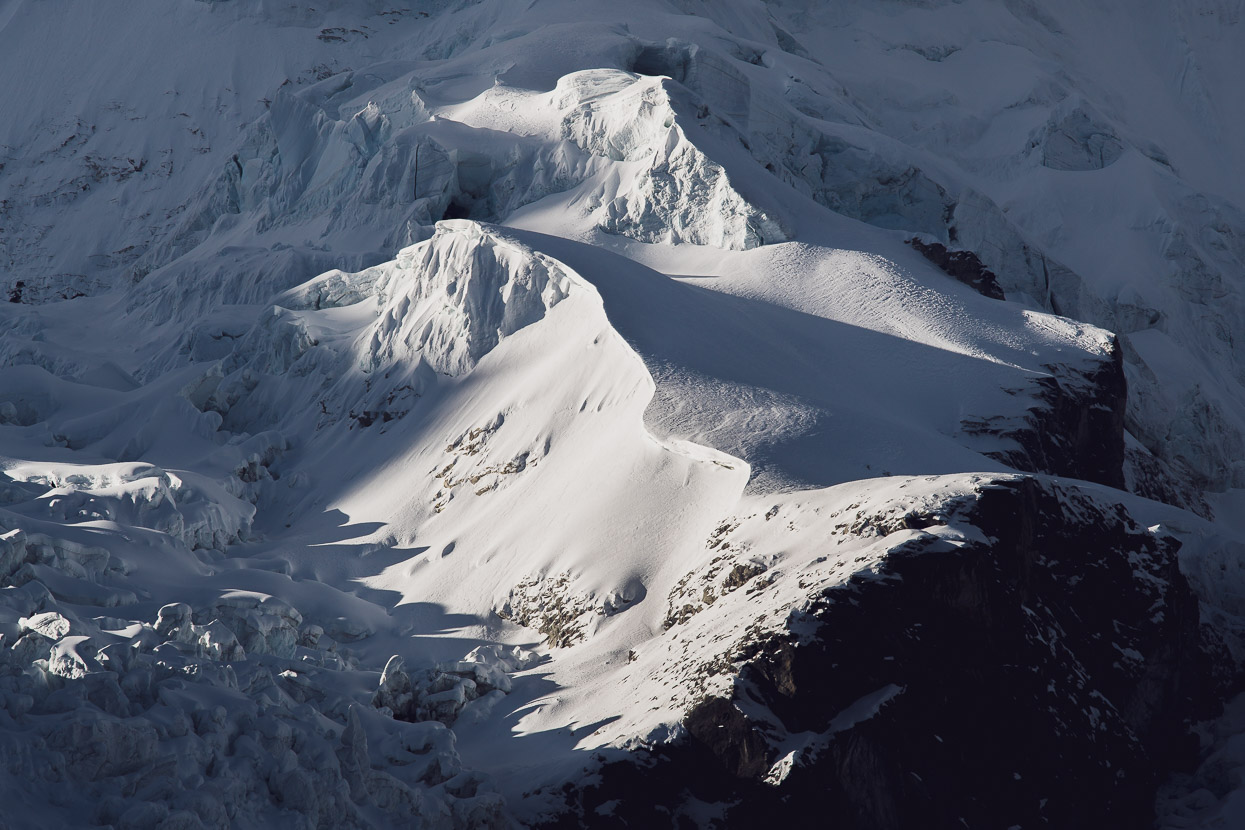

After a few bends in the road we finally caught sight of one of the Cordillera’s most famous icy giants towering over the foothills: Chacrarahu (6108m).

Some six riding-hours later, after passing through Yanama for lunch and resupply, we were into the alpine again. The valley had fallen into the shade and the air had a bite to it.

We made camp on the shore of a laguna, almost able to fill the billy without leaving the tent, while the icefields of Chopicalqui, above us, caught the last glow of sun.

Dawn broke cold and colourful.

Revealing a landscape photographer’s paradise.

I followed the shrinking shadows onto a roche moutonnee, a perfect vantage point to take in the colours, textures and details of the land.

It even had a little lake on top of it. Another crisp reflection…

But more awaited us. So we packed camp and hit the road, struggling at first in the thin air of 4400 metres and feeling yesterday’s long climb in our legs.

The road wound its way up another 300 metres, past more gorgeous lakes.

Until finally we passed through the narrow rock notch of the Portachuelo de Llanganuco to the western side of the Cordillera, and a view to die for.

We lifted our jaws back up from the road and headed slowly down. Chopicalqui seeming to loom above as we left the pass.

While 1000 metres lower the glacier-fed Lagunas de Llanganuco added some brillant colour to a dun landscape.

And down we zig zagged, with northern views of the Huandoy group of peaks and Pisco to the right.

Around a switch back, and the view changes to Chopicalqui and the north and south peaks of Huascarán, Peru’s tallest at 6768 metres – a veritable beast of a mountain.

Huandoy Sur’s 800 metre-high south face (in shade) of icy granite.

We dropped to the valley floor, had some lunch, and left most of our gear at the park ranger’s building that’s at the upstream end of the eastern Llanganuco lake (the first one you arrive at). Our mission for the afternoon was to take the popular walk to Laguna 69, below the south face Chacraraju.

We rode the bikes the first four kilometres from the base building and left them locked and hidden in bushes to the side of the track.

Huascarán framed by the Quebrada Demanda as the afternoon shadows crept across the valley.

The sun had just dipped below the ridge of Pisco as we reached the lake at 4700 metres and already the cirque felt like a giant fridge. With the crowds of the day long gone the lake had a peaceful – silent – ambience as cloud swirled around the ridges high above us.

After about 20 minutes we headed back down to the hanging valley and meadow below the lake to photograph Huascarán Norte as it caught the light of the setting sun.

Darkness was falling and the moon rising as we backtracked further to the small lake at the lip of the last big descent of the walk. As we arrived the south face of Chacraraju (6108m) was starting to illuminate with the moon light. A stunning sight and well worth a noctural walk/ride out for.

We got back to camp at about 9pm. In the morning we woke late, the sun just moments from breaking over the valley. We waited until the warmth of its rays hit us before we emerged from the tent and breakfasted in the sun; enjoying a very relaxed morning (for a change).

Although we have full cold-weather gear with us now we’re still using very lightweight (+5 deg C ) sleeping bags and so high camps have us sleeping in all our clothes and still barely staying warm enough as the nighttime temps regularly drop below freezing. We’re looking forward to our warm bags waiting for us in Huaraz.

Packed up we slowly meandered down valley, passing the stunning western lake, and finally through the steep and narrow granite valley, carved eons ago by a giant glacier.

We emerged onto the hot and dry slopes of the Callejon de Huaylas, the huge valley that forms a western corridor along the Cordillera. Above us the western faces of Huascarán glistened in the sun, a massive backdrop to the fields and pastures of the farming communities that surround the mountain.

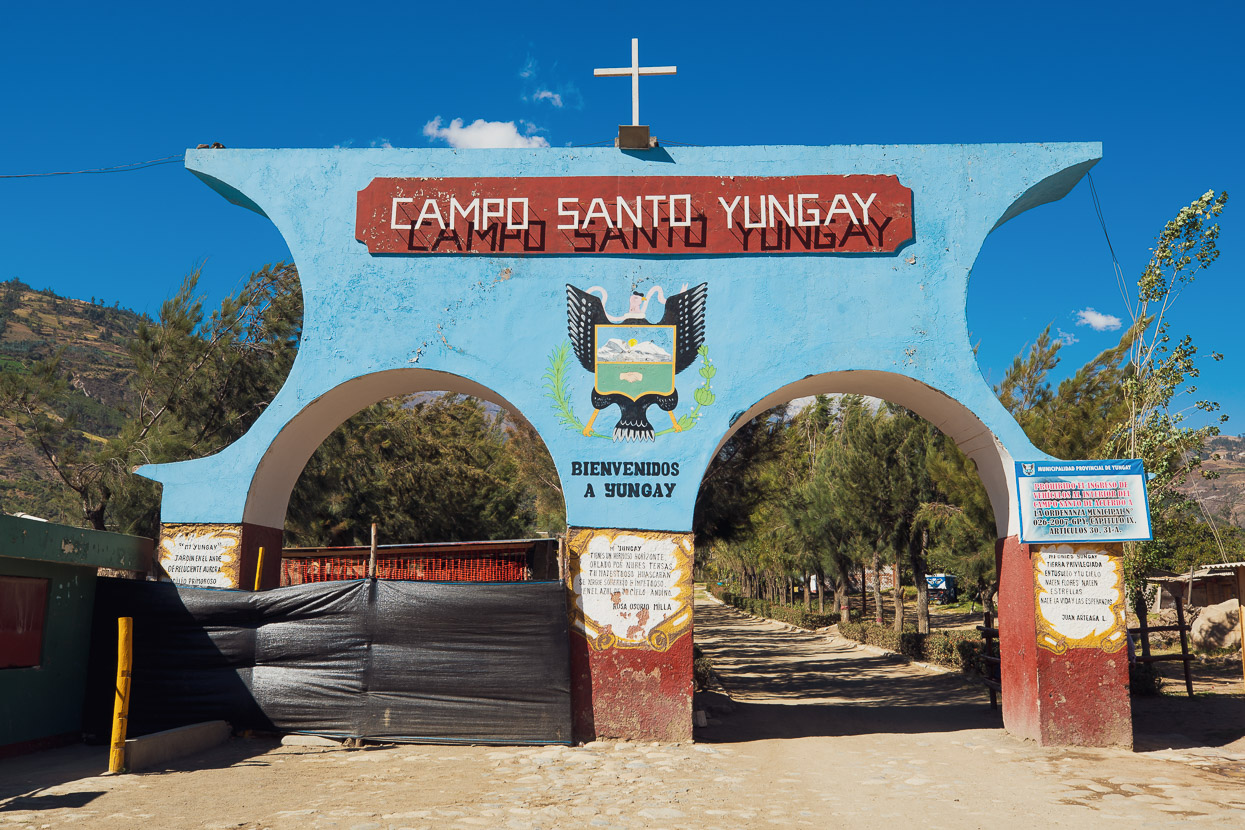

This post ends with the sobering story of Yungay, the town that was buried by a landslide in 1970.

Yungay was recognised as one of the most beautiful towns of the valley, when in May 1970 a 45 second, 7.9 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Peru caused widespread damage throughout the western cordillera, destroying Huaraz and a number of other towns. The violence of the earthquake dislodged an 800 metre-wide section of ice cliffs from the summit of Huascarán, as well as a huge quantity of unstable rock. The falling debris propagated into a colossal, liquefied, landslide that travelled 15 kilometres down valley at speeds up to 500kph.

By the time it reached Yungay – where many of the town’s residents had rushed to the church to pray, following the earthquake – the avalanche was nearly a kilometre wide. The town was completely engulfed and over 20,000 residents buried beneath mud, rocks and ice several metres deep. The only survivors were a handful of residents lucky to coincidentally be on nearby high ground.

An eye-witness account: “We were on our way from Yungay to Caraz when the earthquake struck,” survivor Mateo Casaverde recalls.

“When we stepped out of the car, the earthquake was almost over. Then we heard a deep, low rumble, something distinct from the noise an earthquake makes, but not too different. It came from Huascarán. Then we saw, half-way between Yungay and the mountain, a giant cloud of dust. Part of Huascarán was coming toward us. It was approximately 3:24. Where we were, the only place that offered us relative security, was the cemetery, built upon an artificial hill, like a pre-Incan tomb. We ran approximately 100 meters before we got to the cemetery. Once I reached the top, I turned to see Yungay. I could clearly see a giant wave of gray mud, about 60 meters high. Moments later, the landslide hit the cemetery, about five meters below our feet. The sky went dark because of all the dust, mostly from all of the destroyed homes. We turned to look, and Yungay, as well as its thousands of inhabitants, had completely disappeared.”

Excavation at Yungay is banned and the site has become a huge memorial park, with roses planted atop much of the town’s original centre.

The wind rustled the palms and the air was warm and dry as we walked slowly through the site; attempting to imagine the town that was and the 22,000 people entombed beneath our feet. The ground is hard, like set concrete and it’s chilling to imagine how instantaneous and final the destruction of the town must have been.

Like an accusing finger a crumpled intercity bus juts out of the earth, one of only a handful of visible remains. House- and car-sized boulders dot the flat ground, along with a chunk of the brick church, which is the only building to be partly visible.

Ricardo Peñaranda was one of roughly 300 children who survived the landslide because they had been taken to a circus on the outskirts of town. He was 13 at the time. I can’t begin to imagine the trauma this guy must have been through, but these days he contributes to his income by selling souvenir booklets at a stall inside the memorial grounds.

And us? We pedalled on down to the next sizeable town along the valley, Carhuaz, where we took a day off and prepared for crossings number three and four of the Cordillera Blanca divide.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: Andes gear lists and equipment reviews.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Loving the armchair travel. Despite the snowy alps & fantastic scenery, love to see the personal side of life; the mud brick houses & the womenfolk in their colourful skirts & the ever changing varieties of hats. Do the children learn English in the schools ? Or are you becoming very proficient in Spanish ?? Hope your “skittery days Are few & far between ! Must be hard to handle on a bike ! Really enjoying the ride. BRAVO.