Part one of the ‘Oh Boyaca’.

From San Gil we joined the Oh Boyaca bike packing route which forms a 600 kilometre semi-circle as it curves its way through the highest country of the Boyacá department.

The route was first written up by Filipino bike packing duo Dean and Dang and sounded like a perfect fit for our Colombian biking ambitions; taking in some of Colombia’s unique páramo (alpine plant zone), as it traverses passes over 4000 metres, winding and climbing its way past the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, one of the country’s few glaciated ranges. The route winds its way through many colonial mountain villages and, as we have come to discover, some amazingly diverse country which can seem desert-like in the morning, jungle-like in the afternoon and alpine by evening.

In the best Colombian cycling traditions, the Oh Boyaca is all about mountain riding, and we were right into it on a backroad out of San Gil, climbing through bamboo forests, the bergamot scent of flowering coffee plantations and higher, pine forest.

We joined pavement for a while, passing through a rural town, and then back to dirt as we hit the first really big climb of the circuit.

A long and winding 1000m climb through lush hill country, topping out at 2570 metres. At a mellow gradient it was a chance to find our climbing legs again after the slow build up we’d had coming through the foothills.

We ended the day in Onzaga, a pretty colonial town nestled in a deep valley with 4000 metre ranges towering behind it. We’d met the mayor of this town back in Mompox and he’d said at the time we should look him up when we arrived. We’d put in a big day to get there from San Gil, climbing over 3330 metres of elevation (possibly our biggest ever climbing day) and rolled into town shortly before dusk. We caught up with Hernan, the mayor, in the morning – sharing a coffee and updating him about our ride, but our conversation was interrupted by the arrival of an army officer who looked like he had more important business than a couple of Kiwi cyclists.

We decided to take the rest of the day off and see more of town – hiking up the steep hill in the background of the photo to the Mirador Señor de los Milagros (God of Miracles), where a giant concrete crucifix scupture stands, decorated with prayer offerings. Many of them were dog-tags from Colombian soldiers.

Perfect weather the next morning as we ride deeper into the hills on quiet roads; seeing only the odd collectivo (taxi/bus) and milk truck.

It was a two-climb day; the second taking us over 3000m for the first time and following a little used double-track through a remote valley, making a really nice section of riding.

Below, Colombian power-bar: Bocadillo, a cheap and sugary snack made from guava that keeps us going on the big hills.

On the top of the pass at 3000 metres the air was cool and we were surrounded by alpine plants and patches of cloud forest. By the time we dropped to Soatá at 1970 metres our surroundings were dry, cactus-dotted and stark. Steep, eroded mountainsides surround the town which sits on a small plateau and it felt as if we’d ridden into a different country.

Dropping further to the canyon floor the next morning I cut my front tyre sidewall on a sharp rock. The tyre went flat immediately with a 15mm cut, but we stitched it in-situ without breaking the bead/rim seal and successfully reinflated it, added more sealant and were back riding in about 25 minutes.

Essentials: Leyzene Micro Floor Drive. We adjust our tyre pressure often for different road conditions (i.e. pavement, dirt, super rough) sometimes a couple of times a day, and this pump makes short work of getting them back to pressure. Its high air volume helps with seating/sealing tubeless tyres in a pinch too (but not always – it depends how tight the bead is).

We use the small syringe for adding sealant through the valve hole after unscrewing the valve with the Leatherman Juice S2. We carry one of these small 2oz bottles of sealant each for essential top ups such as this. Superglue (the flexible gel-types are best) is good for sealing up needle holes and creating an airtight ‘scab’. You can also use patch glue.

A mercifully gently-graded, but long paved climb and descent led to San Mateo where we spent the night.

A lonely chapel high on a ridge above town. Lofty worship sites such as this are quite common in Colombia. Closer to God and Heaven I suppose… The indigenous people of the Americas made their temples high for the same reason.

After another long climb out of San Mateo we finally got a view of the glaciated peaks of the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, the highpoint of the Cordillera Oriental of the Colombian Andes at around 5200 metres. From here the road dipped down for a long plunge to the valley and a final climb up the village of El Cocuy.

A couple of empanadas and a coke sufficed for lunch as we passed through the small town of Panqueba, where rich – hallucinogenic even – murals decorated the town’s bare walls.

After four riding days from San Gil we arrived in quaint and quiet El Cocuy.

As we’ve gradually climbed into the Andes – valley after valley – pass after pass – the towns have become slightly higher each day. El Cocuy sits at 2700 metres and has a more unique feel than the others with its terracotta tiles and uniformly painted white and green buildings dominated by a bright yellow church.

Arrive in town between midday and 3pm and you’d swear it was a ghost town; the businesses – what few there are – all close for lunch and siesta. But by 4pm the town bubbles to life again. Campesinos (farmers) chat on street corners, distinctive in their brown wool ponchos, while the women often have tightly plaited hair and felt hats. Sheep and cattle graze nearby paddocks and horses trot the cobbled streets through town.

While the sun is hot during the day, the wind can be cold and evening brings temps around 8-10 deg C. The town’s raison d’etre is farming, but on a much more low key scale to the lowlands. Here people seem to run just a few head of sheep, cattle or goats. Each day several ‘milk trucks’ do their run, driving the windy dirt roads beyond town, collecting milk from small aluminium urns left outside the fincas, hand milked from the cows of course.

In the shops you can buy cheap locally made cheese and yoghurt made from the very same milk that’s collected from roadside urns.

El Cocuy is the gateway to the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy; a still-glaciated (but shrinking) range of angular rocky peaks and sweeping white snow aretes reminiscent of New Zealand’s Mount Aspiring National Park.

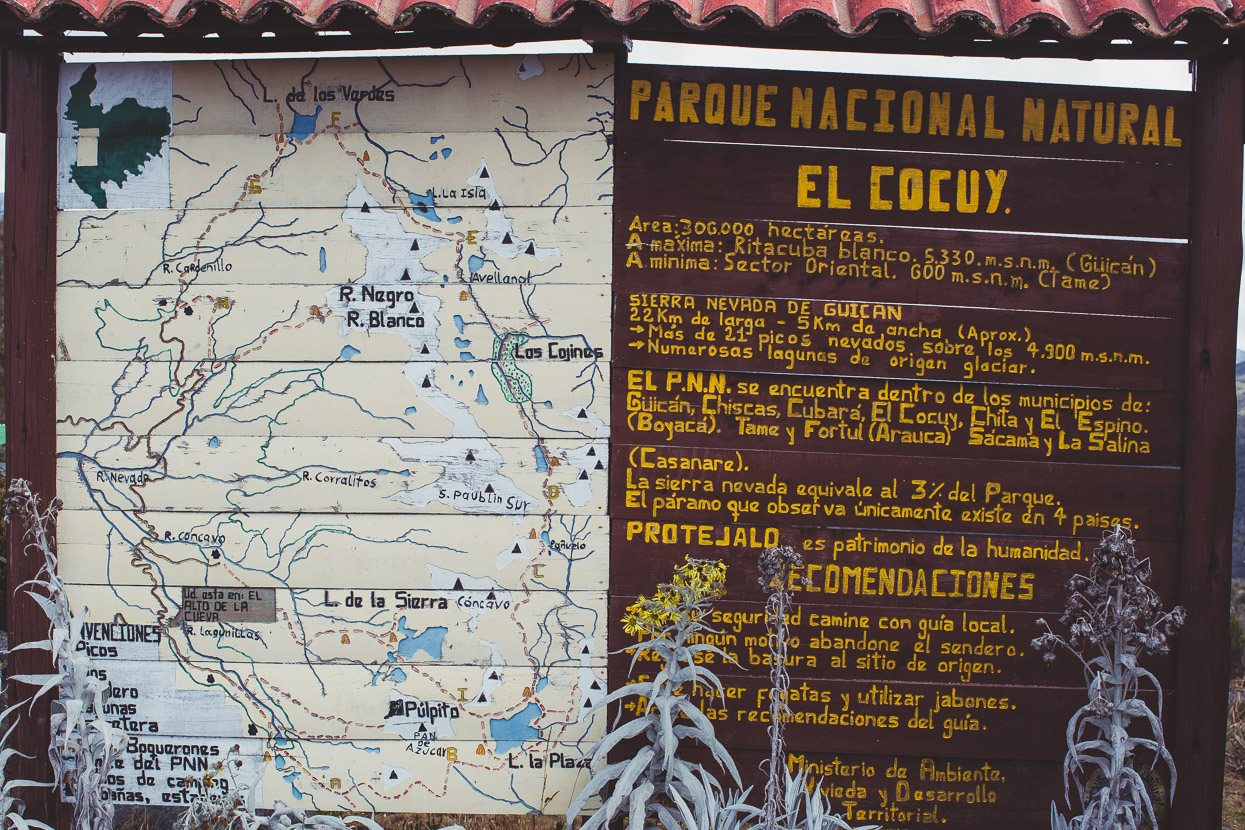

Sadly disputes between the government, the indigenous people and the threat of mining has led to near draconian access restrictions and you can now only enter the Parque Nacional Natural del Cocuy via three different day hikes, to the snowline only and a guide is mandatory. The cost of park access, plus a guide was prohibitive for us so we rode to one of the trailheads and camped nearby on land owned by a contact we’d made in the village. This meant we could still enjoy Colombia’s distinctive páramo (subalpine plant zone) and soak up views of this complex range from the craggy viewpoint near the park entry at Valle de Lagunillas.

We spent two nights camping there at 4022 metres after the 1300 metre dirt road climb from town. Temperatures dropped to -4 deg C overnight, leaving the land and our tent coated in a lick of frost. Through Central America we have not carried any cold weather clothing at all and we are awaiting a parcel of Andes-appropriate wear from sponsor Kathmandu, so between Giron, San Gil and Cocuy we’d assembled a set of cheap cold weather clothing each from bargains found in the market and local stores. Fleece, thermals, gloves and synthetic-fill jackets. Heavy – but good for now.

By night the afternoon cloud clears away, revealing the densest and brightest display of stars we’ve seen in a long time.

We rose early for sunrise and spent the rest of the day just observing the landscape, relaxing and reading amongst the swirling cloud and the ever changing mountain light.

As the sun rises over the range it reveals previously unseen details and textures. It’s a landscape of incredible scale and depth. One we’d love to see more of.

We wandered along a ridge parallel to the entry road (as far as we were permitted) checking out the plants of the páramo, many of which bear similarities to New Zealand alpine plants. But the iconic plant of both Colombian and Ecuadorian páramos is the magical frailejon – a friendly furry triffid-like plant that can grow over five metres tall.

With tall, thick leaves like the ears of a hare, they come in 130 varieties, and are a keystone species for the fact that they harness atmospheric moisture from cloud and mist. That moisture subsequently feeds into the ground which supports the smaller ground-covering species and also releases into waterways. These plants grow a fraction a year and the oldest reach several hundred years in age.

After two nights camping on the edge of the park we returned to El Cocuy via Güicán, making a complete loop through some stunning formerly glaciated country and saying goodbye to the highest country temporarily. We still had nearly 400 kilometres remaining of the Oh Boyaca and a few more visits to the páramo coming up.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.