It was in mid 2020, during the pandemic, when Brian Alder, creator of Tour Te Waipounamu first brought the concept of this unique race to my attention. Brian was seeking some feedback on course routing, as well as applications to participate in the inaugural 2021 edition of the race.

The concept captured both mine and Hana’s attention immediately. We’d been in the midst of a multi year bikepacking tour of the American Continents when Covid forced us to abandon South America and bolt for home in New Zealand. Tour Te Waipounamu (TTW) provided a focus and a goal for the two of us and was a big contributor to keeping our spirits alive after such a big disruption to the life we’d come to know on the road over three plus years.

Prior to TTW the only brevet/race I had done was the infamous Petit Brevet, which tackles over 8000m/26,000ft of elevation gain over 300km/186mi among the gravel and quiet paved roads of Canterbury’s Banks Peninsula. I was high in motivation, but short on racing experience.

Although the touring Hana and I had done overseas had been hard, with all-day Andean climbs, high altitude, massive hike-a-bikes and long back-to-back days, it’s not the same as bikepack racing. Typically, touring takes place at a lower average heart rate, you sleep normal length nights and stops are much more frequent. I had miles in my legs, but not racing miles, and developing that skill would take longer than I imagined.

→ Riding the Hogs Back Trail, Craigieburn. Day two, TTW 2024. Photo @antonmcgeachen

Prior to the first TTW, the e-book Touring with a Sense of Urgency was a useful resource, as I absorbed every gem of wisdom about race craft. The book spoke to me: the descriptions of 19 hour days and fast turn around sleep stops resonated strongly and I imagined myself doing this in detail. It didn’t sound that hard, it just sounded like you had to be disciplined, be prepared to ‘be the problem solver’ and ‘play the long game’ both of which were concepts that heavily informed my approach to TTW when it finally came around. But it was harder than I thought.

To be honest, there is not much in bikepacking that feels that hard after you have carried 18 days food and fuel over high passes on the sandy ‘roads’ of Northern Argentina’s Ruta de los Seis Miles, or pushed a heavily loaded bike up mule trails at altitude in Peru. Kurt Refsnider’s oft mentioned phrase ‘normalising difficult’ is referred to often in the context of preparation for TTW, but we’d ‘been there, done that’ in the Americas and learned to face difficulties with equanimity.

But the challenges that my first two completions of TTW threw at me were of a different nature: My body letting me down, not my mind. In preparation for the first TTW, my first attempt at ‘racing’ a bikepacking route didn’t begin well. The loosely organised Kahurangi 500 event of late 2020 provided a first opportunity for me to have a crack at very long racing days but on day one I developed pain and swelling in the back of my knee that turned the ride into a battle to finish. Two days later I limped into Murchison barely able to bend my leg to get on the bike.

In the first TTW I experienced distracting achilles tendon pain just halfway through the second day. When I reached Methven two and a half days later I struggled to walk, and spent 36 hours there waiting for the swelling and pain to reduce enough for me to continue (in last place). I finished that year, but it wasn’t pretty. The achilles issue was a problem to be solved and I was determined to finish within the time cut, doing many of the climbs pedalling with my heel.

I spent months rehabbing and strengthening both achilles during 2021 in preparation for the 2022 edition of the race, including having ultrasound guided saline injections into the site of the injury. But only two days into the 2022 race the now familiar pain of crepitus in the tendons was creeping back in. I made it to Methven and bought some plastic flat pedals, which took some getting used to, but allowed me to offload the tendon sufficiently that I could finish the race – and still remain within the top 10. That year gave me an insight into my potential for the race, as I realised I could cope ok with short (3hr or less) sleeps, and I seemed to get stronger in the final days of the event.

In preparation for 2024, I incorporated more core, glute and hip flexor strengthening and I decided to convert to flat pedals for the duration of my training (I’d used them in 2022/23 for five months back in South America too) and although I still experienced some achilles aches, they seemed a much more reliable option for me. Having done much the same training for 2024 as I did for 2022 (Kurt Refsnider’s Ultra MTB 4-month plan), I didn’t expect to be much fitter, but hoped to shave a few hours off my time by refining my efficiency at stops and taking slightly shorter sleeps.

This year I finally got a ‘clean’ race, with the serious achilles issues that plagued me in the past absent. Of course there was some pain, but no more so than I think affects the average competitor in TTW, along with moderately swollen knees, aching in the neck, a sore bum, and sore wrists on some of the rougher descents. Instead of managing a problem for most of the race, I was free to devote my energy to concentrating on riding the best ride I could, using my time well and weathering the typical mental and physical highs and lows that come with ultra endurance sport. Finally I became the racer that I’d visualised back in 2020; riding long and sleeping short with a cooperating body and an unburdened mind.

Bike choice & set up for TTW 2024

For 2024 I changed from the Otso Voytek I’d used in the first two editions of the race, to an Otso Fenrir Stainless 29er. My Voytek is set up with 27.5 wheels for adventuring on plus tyres so I’d used 2.6 inch tyres in the first two races, which was great for comfort and control on the race’s more technical or chunky sections, but a little heavier and slower on the road. I can’t run narrower than 2.6 on the 27.5 wheels, or the BB sits too low. But aside from that I had a lot of fun riding the Voytek on the TTW route.

The Fenrir’s geometry felt optimal for the diverse course, feeling stable and predictable on both low speed singletrack, steep climbing and also fast gravel downhills. It’s a great all rounder. The Fenrir is quite a short reach bike, set up with a flat bar, which suits my preference for an upright position (neck trouble) really well.

2.35 inch Vittoria Mezcals and 29 inch wheels probably gave me a bit more speed this year, but the larger wheels were noticeably more awkward when carrying the bike over fallen trees, streams and deep tussock – something that’s easier if you’re taller. I ran the Fenrir with a 28t chainring and Shimano XT 10-51 cassette; a SID Ultimate 12omm fork with lockout (excellent); Fox Transfer dropper post; Magura 2- and 4-pot brakes (160/180 rotors); and Wolftooth Waveform flat pedals.

There are more details in my video, linked at the end of the blog.

→ The Otso Fenrir Stainless, set up for TTW 2024.

→ Cape Farewell, the start line for Tour Te Waipounamu (2024).

Day 1: Cape Farewell to Murchison

268km | 3463m elevation gain | 15:00 elapsed time | 3 hrs sleep

Drafting is allowed for the first 30km to Collingwood, but this year the pace was mercifully much more reasonable than previous years, for the first half, at least. I was sitting about ten people back from the front and just a few kilometres into the ride when a dropped water bottle hit the road right in front of my bike. We were moving at probably 30km/h and my front wheel missed it by centimetres, while my back wheel went over it. My imagination plunged into what might have happened: a hard crash on the road, the end of my ride. Perhaps the near miss was a sign of good luck.

On the 800 metre Rameka singletrack climb a few of us came together and I climbed most of it with Andy Hovey, Lewis Ciddor and Matt Quirk close by, sometimes in conversation. The technical upper half was super greasy from rain which didn’t go well with tyres hard for the road, so I was on and off the bike a bit more than usual.

I was mostly on my own for the Motueka and Baton Valleys. I felt focussed and positive and I concentrated on drinking and eating frequently; getting food in the bank in anticipation of a diminished appetite later in the race.

162km in, at Tapawera, I stopped and resupplied for the following 225km through to our resupply boxes at Boyle Village (race participants post food parcels to this remote service on the Lewis Pass highway). I chomped down a steak and cheese pie while I packed food and filled my water, and slowly drank a coffee milk as I rode the first few kilometres out of town, but by the time I reached the bottom of the 400m pylon road climb a dull nausea had settled in. It was hot on the climb, but I rode most of it and then tried to take on more food and water riding through to the 550m climb up the Porika Track. I felt better than expected riding up the steep but beautiful road under a canopy of beech forest, surrounded by thick ferns, and for the first time made it down the super rough and loose descent in daylight.

Climbing the smaller Braeburn Saddle I caught Emma Bateup and a couple of others. Emma said she had cooked herself on the exposed pylon road after running out of water. Although it was only 9:50pm when I rolled into Murchison, I decided to stick to my plan and sleep for three hours in a cabin. Dinner was my premixed go-to of cold instant mashed potato mixed with chicken stock and milk powder, along with a packet of tuna. I was over an hour up on my 2022 time.

→ Joe Nation, 2024 winner and course record breaker on the beach section after Collingwood.

→ Me reaching the top of the Porika Track on day one. Photo @antonmcgeachen

→ About to drop into the steep, rutted and rocky descent off the Porika down to Lake Rotoroa, Day one. Photo @antonmcgeachen

Day 2: Murchison to Dampier Range (965m)

192km | 3219m elevation gain | 19:45 elapsed time | 5 hours sleep

I was away about 2.20am, feeling motivated and looking forward to getting the next 130km to Windy Point out of the way. Beyond there, TTW really gets going, as it hits the first technical singletrack, followed by the Dampier Range crossing.

As I headed up valley and into the climb up Maruia Saddle I passed a string of cyclists camped up. Richard Dunnett caught me about halfway up the Maruia Saddle climb and we yo-yoed in pace most of the rest of the way to Springs Junction as night gave way to day. Richard said he’d been sick the previous day and stopped to wait for the store to open. Next came Lewis Pass – the longest sealed road climb of TTW, which went by quite fast in the early morning calm and I rolled on down through the beech forest and river flats to Boyle Village.

I’d packed 4.6 kilos of food into my Boyle resupply box, to get me to Methven (and possibly further), over 250km and 5000m of elevation gain away, over some of the hardest terrain of the race: many hours of technical singletrack and hike-a-bike, and a massive push and carry over the only partially tracked Dampier Range, and beyond into the remote Esk Valley, then the Craigieburn singletracks and a long gravel and road bash out to the Canterbury Plains. This section had taken me 43 hours total time in 2022 (inc two ~4hr sleeps) and I’d estimated the same this time.

I dropped a no-doze to sharpen myself up for the singletrack as I battled towards the appropriately named Windy Point. This was my 6th time across the Hope Kiwi singletrack and I know it well enough to know what’s around the blind corners and what rolls for me and what doesn’t. Despite having some of the lines dialled in, there is still a lot of on and off; short steep pushes through stream gulches and steep, rocky and rooty sections of track. It’s a physical, full body workout. It took a while for me to warm into the different use of muscles and find some flow for the technical riding.

I passed Slo-mo (Evan Woolf) and Emma Flukes on the way to Hope Kiwi Lodge, and continued to the next stream crossing where I ducked down out of sight behind the bank to take on more food. I avoid places where riders might congregate as it can be distracting. I also avoid being the rabbit – being in sight is a motivator for racers behind you. By this time in TTW 2022, both my achilles had been quite sore, as well as the anterior tibialis tendons in the front of my ankles. It seems that a bendier flat pedal shoe (I was using Adidas/5.10 Trail Cross XTs) is much more forgiving for me on that sort of technical and HAB terrain.

Nevertheless, after my break Andy Hovey and Matt Dewes were in sight behind me as we crossed the open grassy meadow of the upper Kiwi Valley. Andy is a good mate and we talked as we rode and pushed up the singletrack to Kiwi Saddle before more technical riding and hike-a-bike through to Lake Sumner.

The Hurunui River (the biggest crossing of the race) was a straightforward wade and I was with Andy again as we tackled the steep farm track over to Lake Mason. The track around the side of Lake Mason is a confusing mess of scrub, windfall and intermittent technical singletrack and we caught up to Adam Rozsa as we zig zagged our way through, looking for the most rideable line.

Like most, we got confused at the crossing of the Hurunui South Branch and took a while to find our way down the steep bank to the river, by which time we became a loose group of four: me, Andy, Matt and Adam. We followed 4WD roads though a beautiful high country landscape, warm in evening light, towards Deep Creek. In the distance the treeless Dampier Range formed a foreboding wall across the horizon.

TTW’s hardest challenges have a way of prompting riders to coalesce – a human instinct for safety in numbers I think, and although I’d crossed the range twice before (once solo in stormy weather) it was more fun to have a posse as we worked our way up the initially ridiculously steep gradients until the ridge flattened out a little. In the distance we could see Emma Bateup silhouetted on the skyline, carrying her bike above us. We pushed on as darkness fell, and agreed to stop and bivvy at the last flat section (around 970m) before the goat track sidle. It was 10:00pm so we agreed to set alarms for 3:30am in order to knock out the rest of the climb in darkness and reach the high sidle and descent in daylight.

I hadn’t reached this location until the following day in the previous race, so I was now eight hours up on 2022.

→ Peter Marriott dropping off the Dampier Range towards Andersons Hut at dawn on day three.

Day 3: Dampier Range to Peel Forest

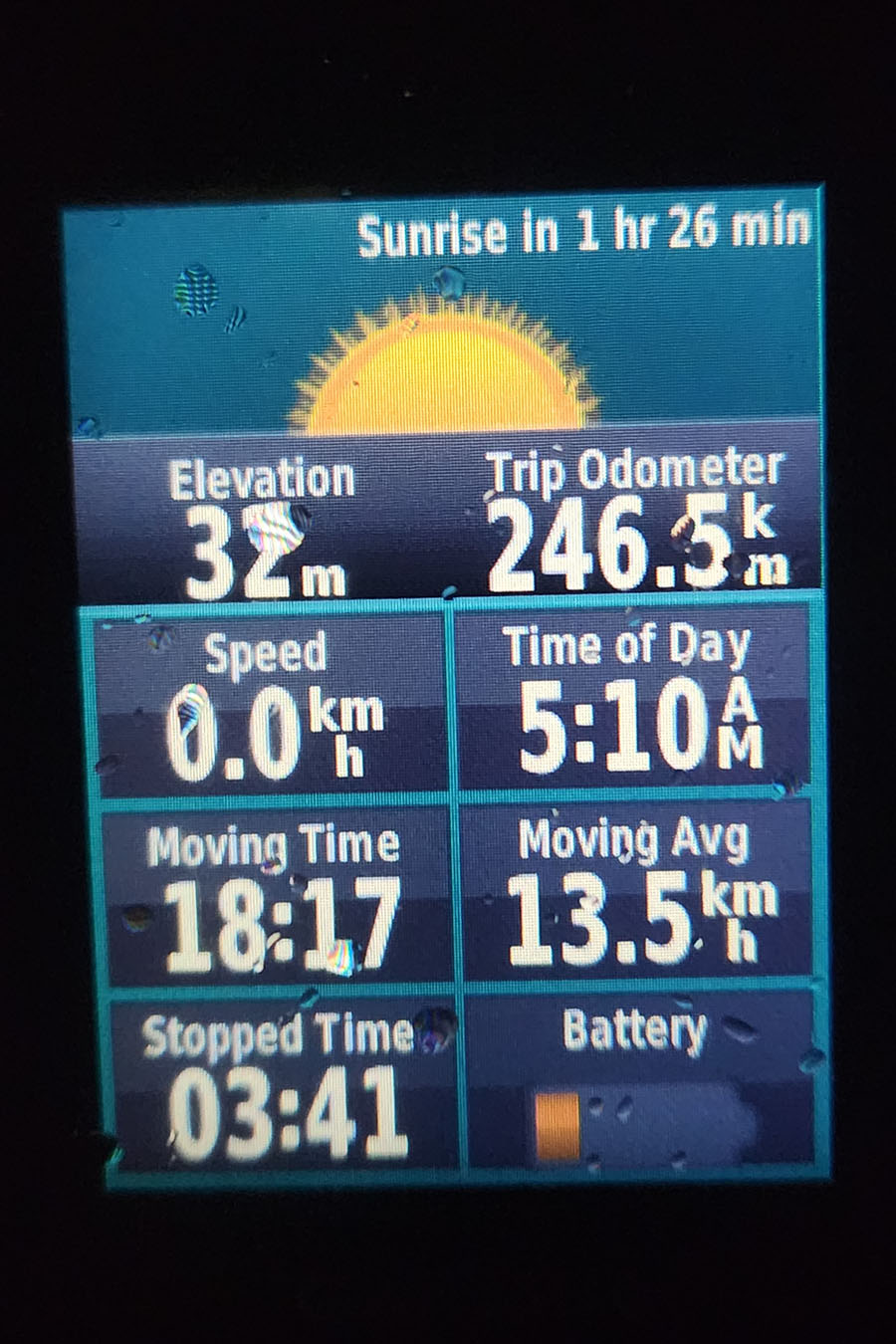

246km | 3423m elevation gain | 23:00 elapsed time | 3.25 hours sleep

Torchlight stirred me at about 3:15am as a tall figure pushed their bike past us. In the fog of waking I thought the person was race organiser Brian Alder (I didn’t know he’d already scratched). Two others had woken us as they passed shortly after we’d gone to sleep. I felt an urgency to get moving, plus Brian would be good company if I could catch him.

I told the others I was going and packed up quickly. Following the ridgeline in the dark I felt strong and motivated, ushered on by the torch beam 15 minutes ahead of me. The shadows of torchlight made finding the vague ground trail easier than I remembered it being in the daylight and I was on a good line all the way to the first sidle. I passed Slo-mo, packing up from his bivvy, and in the faint light of predawn reached the saddle where you drop into the difficult sidle. The person I caught up to there wasn’t Brian after all, but Peter Marriott, who I’d seen on and off the first two days.

Two sets of eyes were much better than one for route finding through the thick tussock of the sidle, and we reached the more defined track to the ridge efficiently. The all-mountain descent that followed is one of the best on the route as a rough singletrack cuts it way down the ridge to Andersons Hut.

Once past Andersons, the ride down the Esk Valley was stunning in the early morning light, with easy rolling on double track and dirt road, interrupted by a few short steep climbs and stream crossings. After a few kilometres Andy passed me and cruised into the distance looking strong. I saw Pete behind me from time to time. It got hotter during the 40km ride to Mt White station and beyond the Poulter River I hit my first big slump of the race. The power faded from my legs and my appetite shut down. I walked hills I’d normally easily ride and struggled onto Andrews Shelter where I pit stopped briefly to attend to a few things at once: my wrinkled and painful feet needed to dry, and as they did, I retaped my achilles, took care of my backside, put on sunblock, forced down some food and filled water.

Although I was looking forward to the 23km of Craigieburn singletracks, this section went badly as I felt powerless and sleepy and walked most of the hills, including the easy road climb to the start of the Dracophyllum Track. I thought I might crash if I continued so I stopped to sleep at the top. Matt rode past as I dropped a no-doze, set my alarm for 12 minutes, put my running vest under my head, and a glove over my eyes. I was out like a light.

Soon after waking I felt much more alert and after 20 minutes had some power back on the climbs. But once out on Highway 73 after Castle Hill Village there was a demoralising gusty headwind to contend with. On the gravel past Lake Lyndon the wind was better and when I stopped to phone ahead to order pizza in Methven (unsuccessfully), Pete Marriott caught up to me. We rode all the way into Methven together, pacing each other side by side into a block easterly as we headed out towards the Rakaia Gorge. Pete booked an Air B&B for the night, so he could resupply in the morning. I was in the fortunate position of having nearly enough food left from my Boyle box to make it to Tekapo, if I could supplement it with something from the pub, so I planned to continue into the night to Peel Forest.

I’d made it to Methven from Boyle Village eight hours faster than last time.

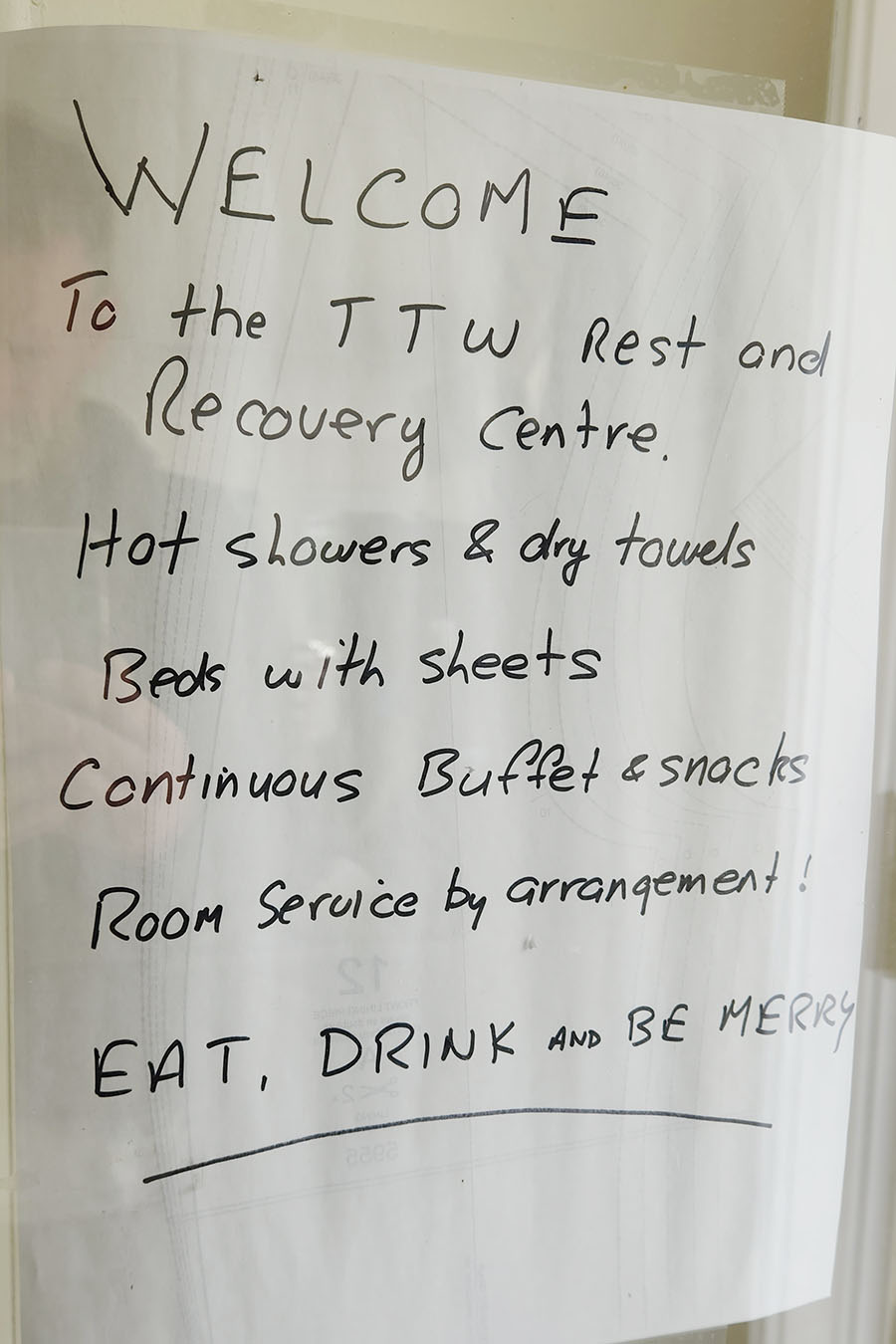

We stopped at the pub, but then a woman yelled to us from a car saying they had reopened the Four Square for riders, so I went there, and found Emma Bateup already eating, sitting on the concrete outside the front door. Pete rolled over too, Big Shaz (Seamus O’Donnell) and Matt Dewes turned up. I bought a little bit of food and had some fish and chips which made a world of difference to my body temperature, mood and energy levels.

Emma soon left, Pete and Big Shaz stayed in town, and Matt D and I rolled out a few minutes apart. The following 68km bash across the plains to Peel Forest passed by in a mesmerising buzz of tyres and the blurry glow of Matt’s lights nearby. After a couple of hours it began to rain. I turned off into the campground at Peel Forest just after 2:30am and parked up outside a locked kitchen block. Emma was already bivvied under the eave around the back, so I took the other end and slept for a bit over three hours.

→ Tarn on the Dampier Range sidle, morning of day three.

→ Lower third of the descent from Dampier Range sidle to Andersons Hut.

→ Hogs Back Trail, Craigieburn, day three. Photo @antonmcgeachen

→ Emma Bateup at the Methven Four Square, night of day three. Emma went on to win the womens’ race for the second time, and set a new womens’ record.

→ Andersons Hut, upper Esk Valley.

→ Esk Valley, early morning day three.

→ Hogs Back Trail, Craigieburn. Photo @antonmcgeachen

→ Seamus O’Donnell, Methven.

→ Looking back down from the Stag Saddle climb. Bullock Bow Saddle is at the red screes in the centre of the photo.

Day 4: Peel Forest to Lake Pukaki

161km | 3340m elevation gain | 19:45 elapsed time | 3.5 hours sleep

I woke, mixed a 3-in-1 instant coffee in my bottle to drink on the go, and hit the road at 6:30am, perhaps 10 minutes after Emma had left, eating a protein bar as I warmed up. The sun was just rising and it was a calm morning. I felt good. One of my reasons to push through to Peel Forest that night was to tackle the long NW ride up the Rangitata Valley before any headwind kicked in as the day warmed. Wind in this big mountain valley can bring your pace to a crawl. Instead it was a fast and pleasant ride and soon I was climbing the steep road into Mesopotamia Station, towards the Scour Stream crossing. This Two Thumb Range section is the Queen Stage of TTW – with its three hard back to back climbs of between 700-900m in elevation gain each, the final of which is the HAB crossing of Stag Saddle; the high point of the route. It’s a remote and beautiful section.

After a while I could see Emma Bateup in the distance, so I upped the tempo and caught her where the climb steepened. Emma and I talked our way up the remainder of the climb, while keeping a good pace on. Emma’s less than half my age, and I reflected on how – like climbing – age difference seems to matter less in bikepack racing and athletes of all ages get to mix it up on the course.

As we began the steep pushing up the relentless wall of Bullock Bow we could see Matt D and Slo-mo about 30 minutes ahead. With rabbits in our sights we steadily pushed up the rock strewn track. It was nice to top out in daylight for a change after my two previous crossings had been met by nightfall at the saddle.

This time I could enjoy the surreal and spectacular view over sprawling red-toned scree slopes, shimmering tussock, alpine lakes and layers of ridgelines. The trail down towards Royal Hut seems audacious at times and is an amazing ride, slicing across scree, down rock scattered singletrack and through the snowgrass – at times barely visible.

→ Emma Bateup on the long push up Bullock Bow Saddle, Two Thumb Range.

I think Emma had dropper post trouble, so by the time I reached the turnoff to Royal Hut I was on my own, and could see the other two ahead. Beyond Royal Hut one of the hardest sections of TTW begins as the ground trail becomes vague and complicated as it crisscrosses a stream heading up a narrow valley towards the main climb to Stag Saddle. Phill Davies, another good mate, caught me at this point. We walked together for a while, but he was moving like a gazelle with his lightly loaded singlespeed and continued at his own pace.

The route leaves the stream abruptly and ascends a steep tussock slope to a big bench, where I caught up to Matt and Slo-mo finally, before a final steep climb to the saddle.

I didn’t stop long on the 1925m saddle. Matt and Slo-mo were on their phones trying to arrange accommodation and food in Tekapo. But I still had just enough food to reach the resupply at Otematata the following morning, so I planned to push on towards Lake Pukaki. I also wanted to get as much of the long ride out to Tekapo done in daylight as possible.

Crossing Stag Saddle is the opening of the Mackenzie Basin stage of the ride and the view from Snake Ridge is remarkable. Tekapo looks tantalisingly close at the end of the turquoise lake, while the ice capped peaks of the Southern Alps lie to the west. All about are tan-toned ridgelines, rocky peaks and the vast expanse of the basin. Snake Ridge delivers you into this landscape as the singletrack twists and turns along its crown.

I stopped at Camp Stream Hut briefly to eat some more substantial food after snacking on bars all day. It was the first time I’d sat down since leaving Peel Forest 13 hours earlier. A few Te Araroa hikers were sitting outside the hut enjoying evening sunshine while they ate dinner. They looked relaxed as the chatter flowed. I imagined that they could smell me from where they were, and I did receive a few sideways glances as I smeared nutella onto broken tortillas and jammed them in my mouth. I was there less than 10 minutes, soon fighting my way through the thorny matagouri towards the brutally steep climb up to the Richmond Trail. Carrying my bike near the top of the steep goat track, my foot slipped and I spun around completely out of control, very nearly falling and dropping the bike which would have tumbled 60 metres down into the stream bed.

Although it’s singletrack, and in a beautiful place, the Richmond Trail never feels particularly fun, with its narrow tyre-grabbing track and staccato bumps. It was a relief to finally hit the gravel and spin the remaining 15km into Tekapo in the dark.

I reached Tekapo around 11:15pm. But there was little to be excited about. Although Tekapo is a tourist boom town, there is no food to be found there at that time of night – not even a vending machine. So I made for the next most useful facility; the toilet block, where I was welcomed by Phill’s surprised sounding declaration of ‘Mark!’

Like me Phill was pit stopping for a quick wash and a sort out after a gruelling day over the mountains. I did a quick food stocktake and was satisfied I had enough to reach Otematata sometime the following morning, so pedalled into the darkness of the canal roads with Phill’s lights in the distance until he stopped to bivvy. By the time I reached the shore of Lake Pukaki it was nearly 3am and raining lightly. I collected water from the lake and crawled with my bike under a fir tree to escape the rain, wriggled into my bivvy bag with my rain shell still on and ate a Radix breakfast that I’d been carrying since Boyle.

My phone had been on flight mode most of the time since the start and I had concentrated on riding my own race. Although I’d had some second hand information about my placing over the course of the race, at the lake I looked at the tracker and realised I was in fifth place, although that was unlikely to be for long with, Phill and Lewis sleeping not far away.

I was 13 hours up on last time now. I set my alarm for just over three hours time and lay down to a deep sleep.

→ Emma descending from Bullock Bow Saddle towards Bush Stream and Royal Hut, day four.

→ Approaching Walking Spur on the Hawkdun Range, day five.

Day 5: Lake Pukaki to Oliver Burn Hut

223km | 4273m elevation gain | 22:00 elapsed time | 90 minutes sleep + one 10 minute nap

It was daylight when I woke – much more pleasant than waking in pre-dawn cold and darkness. It felt more natural and better for my spirits. I was looking forward to reaching the shop in Otematata for a decent feed, and left feeling positive and energetic, as I warmed up along the A2O trail.

The 14km of babyhead river stones along Pukaki River Road didn’t seem so bad this time and I pulled into the toilet block at the eerie Haldon Arm Campground for a fill of water. There was some hand sanitiser in the toilet so I took a handful and smeared it on my chamois to kill anything that might be multiplying there after four very long days without being washed. It seemed to work because I had happy butt cheeks to the finish.

Putting some pressure back in my tyres after the river road I noticed the nipple had fallen off the end of one of my presta cores (never had that problem before), so I switched it out. I was looking forward to riding Black Forest Station in daylight for a change. This hilly section through to Benmore Dam is one of my favourites, with steep climbs and fast descents on a fine, compact gravel surface. The views are over stark, sun bleached ranges as you leave the basin behind.

Leaving Haldon Arm I’d put on my first music of the ride which boosted my positivity and energy. I got to Montys Saddle the top of the main climb, snapped a quick photo, and as I pedalled into the ripper of a descent a song came on that soon had tears pouring down my cheeks and shudders of emotion releasing from my body – a burst of pure joy for the moment, the place, the sunshine, bicycles, long days and the beauty of TTW. Endurance cycling can invoke a pretty amazing flow of emotion; from the feeling that everything is so perfect in that moment to be almost unbelievable, to some quite negative moments where nothing feels right and your problems compound. I tend to get some pretty big highs, but seldom go very low, although when I’m really tired I tend to flatline in my emotions and just try to get the job done without thinking much about anything except eating and drinking.

→ Lake Benmore from Montys Saddle, Black Forest Station. The massif on the horizon is the Hawkdun Range.

I pulled into the Otematata store to find Emma sitting on the footpath surrounded in gear and food. I ticked all my resupply boxes and before I left I dried my feet and elevated my swollen lower legs briefly, while eating a pie, a sandwich, a cream doughnut, and taking on liquids: an essential pit stop before the nine-hour crossing of the Hawkdun Range.

In that time Lewis rolled in and bought an armload of food. While he jammed supplies into pockets, he said he was feeling awesome after a seven hour sleep near the canal roads and was on a mission to push through to the finish. He was amped and focussed and left quickly.

After Lewis and Emma left I lost a few minutes to a malfunctioning e-Trex, which had accidentally been set to navigate to somewhere a long way away, which kept crashing it. Inevitably there was a heaviness to my legs when I did leave and as I climbed slowly up the rough road out of Otematata Station I could see Lewis romping off ahead up the steep climb.

With the burly climb over to Otematata station out of the way I dropped into the Otematata River where it was sizzling hot even at 4pm in the afternoon. I got really sleepy and my power began to fade so I lay down for a 10 minute nap under a rosehip bush. I felt more energetic as I started the hike-a-bike up the steep switch backed 4WD road away from the river. Below, I could see Myles Gibson and Matt Dewes approaching the base.

It seemed to take an eternity to reach Ida Railway Hut as the route wound ever upwards through jagged rock outcrops and treeless windswept tussock country. Shortly before the hut Myles powered past, but we both stopped to get water near the hut, had a brief chat and put more layers on for the cold wind. Myles told me that third placed Steve Halligan had crashed and broken his femur earlier that day, just a few kilometres beyond where we were. I felt really bad for him while I digested that bit of grim news.

As Myles made to leave he turned and said “Well, if I don’t see you beforehand, I’ll see you at the finish”.

I couldn’t resist a bit of black humour and as he rode off I quipped “Yeah, for sure. Break a leg!”

Matt caught and passed me on the way to Wire Yards Hut, but we eventually reached the top of Walking Spur close together and plunged into the big rock strewn descent, with Emma’s lights visible ahead.

At 11:10pm I stopped outside the closed store in Oturehua to get water and eat a burrito I’d carried over the Hawkduns. Matt and Emma rolled in behind me and paused there too, and then a few minutes later Kurt Standen arrived. Like Myles, Kurt had taken a long break in Tekapo and was now picking his way back through the field. We could see from the tracker that Phill Davies was asleep nearby.

Emma left first, but stopped to sleep somewhere on the monotonous 38km rail trail and road section to Moa Creek. I could see Matt’s lights behind me until Moa Creek where I stopped again quickly to eat a pie. Matt passed me there and that was the last I saw of him except for his lights ahead of me for the next hour or so on the gradual 400m climb up to Poolburn Reservoir. My lights were fading and I thought I had two batteries in reserve, but they inexplicably turned out to be flat. I continued with a weak pool of light for the remaining 14km of gradual climbing up to Oliver Burn Hut which I reached at 5am. Beyond the hut the riding is much faster, and continuing with my weak light would have been a waste of time. I also needed to sleep.

I ate some muesli and protein powder that was still left over from my Boyle supply, pulled out my sleep quilt and lay down still fully clothed for a 90 minute sleep. I’d only been asleep for 10 minutes when Phill D noisily stumbled into the hut for a sleep, not realising anyone else was there because I’d dragged my bike inside the tiny two bunk building.

→ The view from Lammerlaw Top on a fine day, looking back towards Lake Onslow, TTW 2022.

Day 6: Oliver Burn Hut to Slope Point

248km | 2750m elevation gain | 22:10 elapsed time | one ten minute nap

An hour later, at 6:40am, Phill left. I slept a few more minutes and left at 7am. By now it was daylight and a moody sunrise was winding down. There was 248km to go with nearly 3000m of climbing and I was on a mission to finish within 6 days. I’d checked the tracker as I left: Emma B was about 2km behind me, and I wondered if I could catch Phill if I kept my effort steady. To the south an ominous wall of layered grey cloud filled the horizon.

I had good legs as I rode on past Lake Onslow, riding the steep climbs up towards the Teviot junction. By now it was raining and I was in full waterproofs and gloves with my hood on. As I turned off towards the Lammerlaws the rain stopped and I wondered if I might get lucky. But it soon came back, more heavily, accompanied with strong wind as the front arrived properly.

Phill’s tracks looked fresh in the mud, so I kept my head down and my legs turning over as I battled on through cold rain, picking lines around and sometimes straight through water filled bogs, through tangled saturated tussock and across paddocks thick with sheep shit, hefting my bike over innumerable gates. The ruts in the road were running with muddy water. I pushed as hard as I could on the steep climbing up towards the Lammerlaws summit, trying to raise my body temperature before the 10km undulating section before the descent. I should have stopped and put on my buff and windproof hat, at least, but instead rode on and got colder as I finally descended in the cold, gusty wind towards Lawrence.

Interestingly, I realised as I descended, that although I clearly recognised the greasy track that dives down a distinctive corridor of fir forest, before dropping to Castle Dent, I didn’t have a memory of this section from 2022 that I’d been conscious of and returned to in the two years since that race. It seems that memories formed in a state of exhaustion are not reliable! I’d also remembered Ida Railway Hut as coming shortly after the top of the steep zigzags out of Chimney Creek, and completely blanked the 13km section between.

The nearly five hours of exposure to the weather on the exposed ridge tops between the Teviot junction and the shelter of the valley into Lawrence, while already in a depleted state, took quite a lot out of me. I hadn’t been eating well. By the time I stopped at the Night & Day store I was shivering and spaced out and probably mildly hypothermic. I got a large hot chocolate, a cup of hot water and a plate of wedges and sat on a bar stool dripping muddy water over the floor while I tried to warm up. Another customer looked me up and down slowly and said I looked like I had been in a mud fight. I called Hana briefly, for the first time in the race, which helped snap me out of my daze.

I put my batteries on to charge in the store, ordered a coffee, because I was still shivering and needed another hot thing, and then fell asleep for a couple of minutes while sitting on the stool at the counter. When I woke I started getting my shit together as quickly as I could.

My drivetrain sounded like a concrete mixer, so I got that sorted, rearranged my clothing (the rain had stopped) and filled water. By now I’d lost some time to those closest behind me: Emma, Myles (who had slept at Moa Creek) and Pete Marriott who I hadn’t seen since Methven. The 57km ride to Clinton is a tedious, undulating series of country roads and I could not find any flow. My core still felt cold and my brain wanted to sleep, but I was determined to reach Clinton first. In my daze in Lawrence I’d failed to buy much food and the finish was still over 100km and 1000m of climbing away

I arrived in Clinton at 10:00pm, well after the shop had shut, and made for the hotel, hoping I could get some more calories. Hot food and a quick nap would snap me out of my lull, and it was worth losing time to those behind me to get some focus back for the final push. They could do pizza, so while I waited I put my batteries on to top up some more. While I ate, the hotel owner sat down at my table and inquisitively commented that I “Looked like I’d been on a long ride”. She was brave, I thought. I was filthy and I stank. But that didn’t deter her generosity after I explained what I was up to and that I was keen for a quick nap. She turned the heater on in a quiet room and offered me her ‘hangover beanbag’ to sleep in. Amazing.

The 10 minute nap did the trick and I wheeled my bike out of the hotel into what felt like a different realm. It felt much warmer. I felt more positive – ready to smash it out to the end. As I rode into the long climb out of Clinton I could feel heat emanating from my core as the food returned some equilibrium to my body.

The restoration from the hotel lasted about 45km and then the wheels began to fall off again after I passed Mokoreta. My sleep at Oliver Burn had been so short and broken that my big push from Lake Pukaki to here was beginning to bite. The flickers of light and shadow alongside the road created mild hallucinations. I was falling asleep for a second or two while riding and weaving around on the road. I had strange moments of dream state fill my consciousness even though I thought I was awake. I stopped and squirted water in my face to snap out of it.

I thought I could see another cyclist’s lights behind me, and the adrenaline helped me hasten my effort and I began to pick up speed, not wanting to be passed by anyone so close to the finish. The flatter roads through the Waikawa Valley couldn’t come soon enough. I hit the coast and knew it would soon be over. I smashed out the next 20km. Cruising up the final short climb before the finish I tried to allow it all to sink in, but I was an emotionless zombie. My primate brain had taken full control: all I knew was to keep moving forward – don’t think, just ride.

And then there I was, standing in the dark, beside a lonely signpost on a windswept cliff edge above the Southern Ocean.

I finished in 5d, 22hr, 10 min, shaving 16 hours off my 2022 time and coming in 8th place. I’m the only person to have finished all three TTWs, although Steve Halligan had been well on track too until he sadly crashed and broke his femur crossing the Hawkdun Range, while sitting in third place.

Although I felt no surge of joy hitting the finish line on that cold, windy morning at 5:10 am, a deep satisfaction soon settled in. I trained hard. I’d tried to learn from past mistakes. I’d done my best in the race and made few errors. I’m very happy with that.

Epilogue

Riding from my house in Lyttelton, it takes just 20 minutes to reach the summit road of Christchurch’s Port Hills. The road traverses the ridgeline – a former volcanic crater – and makes a great ride, but it’s also the conduit which makes accessible a network of singletracks, both for riding and walking. It’s my ‘backyard’ and the place where I did the majority of my training for three Tours Te Waipounamu.

From the summit road, the view of the western horizon – far across the Canterbury Plains – is filled with the layered ranges of the foothills of the Southern Alps. They have many moods; from the smothering cloud of a raging norwester, to the crisp relief of a winter’s day with a sharp snowline, when every detail of the mountains can be picked out from afar. On a clear day, I can see a large swath of Te Waipounamu’s mountains from the summit road: from the Kaikoura Ranges in the north, right down towards the Rangitata River and the peaks that merge into the distant haze.

Sometimes, I imagine myself as a dot amongst that vast landscape, stroke by stroke or step by step inching along valleys and ridge tops deep in the hills, by light or dark, whatever the weather – following the line on my GPS and thinking of little else but moving forward. It’s a journey that seems preposterous in some ways, when visualised from so close to home, with a hot shower and a comfy couch not far away.

Four years ago I hadn’t cycled more than 170 km in a day, and not for more than 12 hours at a time, although I’d had a few big days in the mountains over the years. The last time I raced or engaged in structured training for cycling was in the mid 1990s, when I pursued racing cross country in NZ’s national series and classic races for three years.

New Zealand cycling legend Simon Kennett’s 2008 ride to fourth place in the early days of the USA’s Tour Divide, Olly Whalley’s 2012 win, and Brian Alder’s 2016 fifth place, were all doses of inspiration that contributed to me starting to think about taking on one of the big ultras after I finished cycling from Alaska to Patagonia, and then the pandemic started and Tour Te Waipounamu was created. You could call it a perfect storm.

My experiences preparing for and racing Tour Te Waipounamu have added an immense amount to my life: leaving indelible memories that have been forged from what is, at its base, a very simple activity: moving through the countryside as efficiently as possible, without support and against a clock that never stops. As many before me have explained, this challenge extracts from us some of the essence of what it is to be human; to have extraordinary endurance, a capacity for optimism, a drive to keep moving forward, and a subconscious desire to continue to correct our errors and to improve.

One of the biggest rewards for me from racing Tour Te Waipounamu has been the window into my own physical and mental capabilities and capacity for endurance. I’ve been active in the outdoors all my life, but learning how to ride for 20 hours with minimal stops, to sleep briefly and get up and do it again is a new paradigm. It permits so much insight into oneself; how your body behaves, the mental highs and lows and how you react to challenges. It’s one of the most wonderful tests you can impose on yourself. Perhaps, like a psychedelic experience, it has the capacity to access underutilised corners of our minds and add another layer to our consciousness. That’s how these experiences feel to me; even after the afterglow has subsided, there’s a newfound confidence and trust in one’s physical and mental abilities. Lessons for life.

There’s a thirst for more, but not too soon.

More about Tour Te Waipounamu

Video: Unpacking Mark’s Tour Te Waipounamu Bike

Tour Te Waipounamu Packing List

bikepacking e-book

Bikes, gear, planning, navigation and living on the road

Bikepacking & Off-road Cycle Touring Guide

Our e-book provides a tool kit of skills and knowledge for cyclists who want to get off the beaten track and undertake extended bikepacking tours, with a focus on travelling light. While the information is designed for cyclists planning long distance off-road tours, it contains many tips that are applicable in any bikepacking scenario, long or short. US$19.99

bikepacking e-book

Bikes, gear, planning, navigation and living on the road

Our e-book provides a tool kit of skills and knowledge for cyclists who want to get off the beaten track and undertake extended bikepacking tours, with a focus on travelling light. While the information is designed for cyclists planning long distance off-road oriented tours, it contains many tips that are applicable in any bikepacking scenario, long or short. US$19.99.

Thanks for the read Mark. Incredible, emotional, inspiring to say the least. Enjoy your recovery.

Thanks Helen!

A very interesting and inspiring read. Thanks for both the blog and photos Mark.

Congratulations on finishing your third TTW

As always Mark, an amazing account of your journey with fantastic images. Thank you so much for sharing.

I am on your email list as tim@centrallakesphotography.co.nz

This email will end in March and I have a new one phototim76@gmail.com

Please could you update this on your data base, I would hate to miss out on your adventures and knowledge.

Many thanks

Tim

Thank you Tim! Yes I’ll update your email, no problem 🙂

Wow. That’s an epic adventure brought vividly to life. Thanks for sharing it in such riveting detail. And well done for persevering on so many fronts.

Thanks Gavin. It has been a journey!

Fantastic account and amazing images of an epic adventure that is Tour Te Waipounamu captured beautifully.

Excellent race report Mark, you capture the essence of the race incredibly well.

It was fantastic sharing some time riding and recovering with you!

Until next time..