Late January 2023.

Continuing south within Argentina from Bariloche, long distance cyclists are faced with two main choices: the Ruta 40 to El Bolson, or the Patagonian Beer Trail.

The former is entirely paved, while the latter is a relatively remote off-road journey that ventures off into the sparsely populated and barren pampa of the Patagonian Steepe, crossing a couple of high-ish passes. You can probably guess which way we planned to go. Had we not already cycled south from approximately this latitude on the Chilean side of the border (before crossing to Argentina via Paso Puelo/Bolson) in March 2020 we may well have crossed over to Chile, but it made more sense to see something new. In my previous post we’d already followed the northern section of the Beer Trail from San Martin to Dina Huapi, outside Bariloche.

As good as the route is, Beer Trail is something of a misnomer; there’s no daily rewards at cervecerias, I’m sorry to inform you. There is excellent craft beer, but it can only be encountered at three points along the route: the start, Meliquina, and the finish, and also in Bariloche, which is technically off route. There’s nothing to stop you from picking up a couple of six packs of course, to make the trail more flavoursome, but it will make your bike heavy for the route’s steep climbs. That said, if you’re desperate you can probably find a couple of Quilmes in Ñorquinco, and you’ll most certainly find fun doubletrack.

But, back to the story. The Beer Trail finishes in El Bolson, Argentina where the logical continuation would normally be to ride through the beautiful Parque Nacional Alerces to Trevelin. However, we’d already been to that national park in March 2020 too, after crossing Paso Puelo/Bolson, so we decided to retain the pampa theme for as long as we could before heading west to Esquel and Trevelin. Our longer term plan was to cross Paso Rio Encuentro, which is just south of Trevelin, to Chile and join the Carretera Austral.

A detailed look at the maps on Ride With GPS revealed a viable looking route through pampa country towards Esquel, so we planned to deviate from the Beer Trail at Ñorquinco and make our own way south. Map here, and at end of post.

It was mid-morning by the time we got going from Miguel’s place in Bariloche, with a 8km ride back into town, but soon after that we followed back roads past the airport and picked up the Beer Trail where it joins the RP80. In this photo we’re climbing away from the plain that lies between Bariloche and Dina Haupi.

Before long we were back in the Argentina we’re more familiar with; heat, dusty roads, spiny plants and encounters with gauchos driving their stock.

We rode at quite a high pace for a few hours – the urgency coming from a latish start and the excitement of riding south again – but stopping at the Rio Pichileufu we realised we were hot and tired and decided to lie down for a 10 minute break before continuing to another small stream 12km up the road to camp. Our hiking mission up to Laguna Toncek must have taken more out of us than we thought, because within moments we both passed out for about half an hour.

When we woke we were dizzy and unmotivated so we decided to call it a day there and ride in cooler conditions in the morning (it was about 30C, even in the late afternoon). We set up camp on an inviting patch of grass but as the evening cooled camp became overrun with hundreds of biting ants, so halfway through cooking dinner we had to abandon camp and move to another site.

The next morning began with a wade across the river.

Early mornings out here are stunning, with no wind and warm light. With the landscape relatively unchanging, the sky becomes my focus, with so much of it visible and impressive clouds streaking across above us.

The few farms and dwellings we pass by seem to be abandoned, if not completely derelict. This rusting carcass of a car from a bygone era.

Speaking of bygone eras, much deeper into the ride, far from any good roads we were surprised to see this 1980’s Renault carefully negotiating the double track as it came down a long descent towards us. I think the driver was just as surprised to see us. We didn’t quite catch where they were headed, but they knew the name of our destination for the day and we stood and watched for a moment as the car bumped precariously down the hill. Further on I noticed that some of the road’s ruts and pot holes had been filled in recently by spade – no doubt by these guys as they nursed the car through the mountains.

Near the top of a long climb we saw only the fifth and sixth cycle tourists we’ve seen on the road since we left Mendoza about eight weeks ago. Bart and Tess were heading north from Ushuaia right through South America. We chatted for a little while before wishing them well for the incredibly diverse journey they have ahead of them.

Aside from a couple of really steep sections the day’s ride was a lot of fun. We had tailwinds all day, and the ride feels increasingly remote as you cross the highpoint at 1478m. From there, there is a final climb and then a long descent towards Fitalancao.

But as we rode on, hurried along by a strong wind, the sky began to darken. We could see distant rainfall and the cloud thickened above.

It looked like it was going to be a race for the shelter of the abandoned railway station at Fitalancao before the thunderstorm hit, but we took it carefully on this rocky descent for fear of cutting a tyre at a bad time.

Thunder rumbled and fat rain drops began to hit our backs as we sped along the flatter part of the valley, feeling the urgency to make it to shelter.

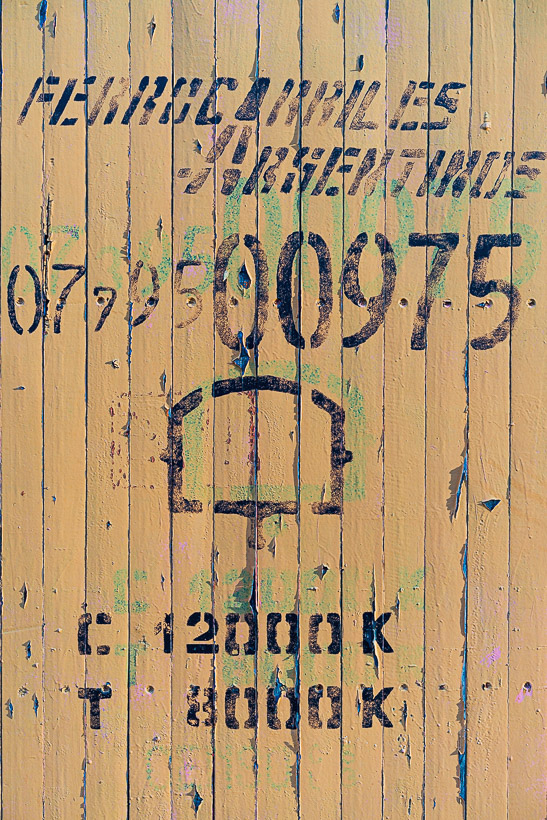

A sanctuary of sorts lay at the abandoned Estacion Fitalancao and we took shelter in the only usable room there, the others having no roofs or destroyed floors.

This room’s provided shelter for many a cyclist before us, as well as local visitors. A hook hanging from the door lintel with blood spattered below it, a discarded sheepskin and a fire in the corner of the room told a story. As did the the writing scrawled on the walls, with one person writing that the nearly derelict room had once been their classroom. So isolated is this place that the school was part of the rail utilities.

After a couple of hours the rain stopped and the gale wind eased and we wandered outside into beautiful golden light that snuck under the storm clouds. The only sound was the wind swooshing through the poplar trees. We were totally alone out there.

The railway is a remnant of the Viejo Expreso Patagonico (Old Patagonian Express) or La Trochita, colloquially. The nickname comes from the narrow gauge tracks the rail system used; trocha meaning gauge and the ‘ita’ being the diminutive (little/small). It was part of a broader network that was meant to unite southern Argentina with the main Argentine Railway Network. The network was planned in 1908, but was fraught with obstacles almost right from the start. Some sections were never connected to others and the disruption of the First World War caused further problems. But the line from Esquel to Ingeniero Jacobacci, which includes Fitalancao and Ñorquinco, was completed in the 1940s, despite much of the work being destroyed by floods. Wikipedia reports that travel on the train, when operational, was so uncomfortable and slow that passengers would disembark and walk alongside the train at some points on its journey. When onboard, stoves in each carriage were used to heat water for maté.

By the 1960s improvements in highways and vehicle speeds, as well as difficulty maintaining the remote railway began to lead to its abandonment. I can’t work out when exactly the section including Fitalancao was closed completely, but it appears to be the early 1990s. These days two very short sections of this once 400km long railway operate for tourism further south, one from Esquel and one from El Maiten. But once essential stations such as Fitalancao are gradually returning to nature. We didn’t realise it at the time, but La Trochita’s forgotten stations would be the theme of our ride for the next couple of days.

The storm’s tail end lingered into the next morning, and we rode in rain showers through more empty pampa until we joined a busier road that led to Ñorquinco, a small town, and another abandoned stop on the railway line. We resupplied there and then continued on the alternative we’d mapped out.

Ñorquinco is just like rural Argentine towns you see further north, but without the brain melting heat: there were very few people around and the place was in state of general disrepair with many abandoned looking buildings. The one open food shop was well stocked enough for us to buy supplies for three days.

I guess it must get hot some days…

We rode on past Ñorquinco’s railway station and down an arid valley. This estancia looked to be abandoned and judging by the state of the poplar trees its water supply had ceased.

When planning the route we’d spotted a 4WD track on the map that would connect us between two dirt highways. It looked temping as a ‘shortcut’ and for the empty stretch of steppe that it crossed. As we rode up the track from the valley below we encountered a truck coming our way. The occupants were an older man and his son, both dressed in traditional farming clothes, with the older man wearing well polished knee high leather riding boots. Essentially we were riding up their driveway, so they tried to tell us we were lost, but when we explained we wanted to cross the empty pampa (which was part of their station) beyond their farm buildings they actually got it – and said we could go for it – explaining that we’d have to climb over a locked gate. Before leaving, they told us to help ourselves to water from the house, as that would be the last we’d see for a few hours.

The buildings in the photo above were at the main farm.

A steep and rough road climbed away from the farm, and then we rode across a high, exposed mesa-like section, with views of empty steppe in every direction.

Once we rejoined the main road (RP4) we rode west into a strong headwind until we’d had enough and stopped at a farm to ask if we could camp out of the wind behind their galpon (shed) which was our new word for the day.

Chorizo and red pepper stew with instant mashed potato was dinner that night. We’ve stepped up our cooking game with heavier and fresher ingredients lately with the riding being generally easier.

In the morning we followed the RP4 for a while and then turned off onto a gem of a 4WD track we’d checked out with the satellite map. This contoured around the hills for a while before dropping steeply down to cross the Rio Chubut.

Some clever gate closing methods are employed out here.

A narrow bridge crossed the Chubut, and entertainingly a stray herd of goats thought we were the bosses and followed us across, until the goat herd spotted them and came running over to redirect them.

Freedom defends itself. We are seeds in the wind that flourish in the fight.

We joined the Ruta 40 briefly and then turned off to Leleque, which is not a town, but a solitary museum just a few kilometres off the Ruta 40, and a little further down the road, a large estancia. The museum’s quite interesting and focusses on the culture of the Telhueche, who were the dominant indigenous people established on the Patagonian Steppe at the time of the European conquest of South America. Patagones (meaning ‘savages’) was the name that the Spanish gave to the Telhueche they encountered on the steppe.

Beyond Leleque the route we had plotted followed a road designated as the Ruta Nacional 2S40 for 60km to the paved RN12. It’s possibly the original route for the modern Ruta 40, and roughly paralleled the La Trochita rail line for most of that distance, although sometimes separated by a kilometre or two.

8km past the museum, alongside Estacion Leleque, there was a locked gate, but no private properly or no trespassing sign, and no-one around to ask, so we removed our bags and climbed over it. Locked gates on land where public passage on foot or by bike is not prohibited are not unusual in Argentina – they’re generally to keep vehicles out.

For the next 48 kilometres we didn’t see a soul, and the road had obviously not been used in some time. The only tyre marks on it were our own. A line of long abandoned utility poles crossed the pampa beside us.

Although we saw no humans, we saw quite a few guanaco and even a few suri, which are a large flightless emu-like bird native to Argentina.

There were two more abandoned stations enroute, Lepa the first.

Where a line of rolling stock lay silently, slowly being ravaged by this harsh environment. A manufacturing badge I spotted on one carriage showed it was Belgian in origin.

We rode on, crossing a couple of arroyos, where we saw a few cattle until we were in sight of Estacion Mayoco, where we planned to camp for the night. This bridge to nowhere almost shut down that plan, but it was still just connected to terra firma. This partly explains why the road appeared unused.

Estacion Mayoco was the most intriguing of the stations we visited, because it felt like a ghost town and had been a small community of railway workers. There were several huts in a row beside the tracks and they were built from wooden railway sleepers. Winters here are savage so it must have been a bleak place to live.

We walked right around, exploring every inch.

And made camp out of the wind in the shelter of one of the huts.

In the morning we walked up the hill above town to a cross on the horizon, where community’s cemetery lay.

And a final look back at Mayoco from the cemetery. Later, where the road joined the RP12 there was another locked gate. We joined the Ruta 40 shortly later and battled on into a strong headwind to reach Esquel for a luxurious Sunday cafe lunch, before continuing to Trevelin for the night.

In Trevelin we Googled for more information about this strange section of road, that appears to be public, but is behind locked gates. Not to mention the historic railway stations that are inaccessible. The land is actually owned by Benetton (the famous Italian fashion brand) who own 2.2 million acres of land in Argentina and they appear to have non-negotiably shut the public out of this area, and anecdotally many other formerly accessible areas too. We got lucky with this section and met no-one who might deny us access by bicycle, but if you’re interested in following it, it’s probably best to try asking at the estancia at Leleque. We don’t know what the actual status is.

As we rode into Esquel we saw on display one of the original engines, tidily restored, which made quite a nice post script to this chapter.

Trevelin marked an important moment in this journey. Aside from the first day’s ride out of Mendoza, many weeks back, this was the first place we’d be visiting a second time, and we’d briefly be repeating some of the same road we covered in our March 2020 ride south through this region. Within a day and a half’s ride we’d be back in Chile.

More soon…

Say thanks with a one-off donation, or check out our Bikepacking guide.

If you enjoy our content and find it informative or inspirational, you’re welcome to show us some love with a donation or a book purchase (US$19.99). The services we use to create our Bikepacking routes and host the website cost money, funds that we’d rather be spending on the road, creating bikepacking routes and content to share with you. Thanks for reading!

Wow, you guys really got out into the good stuff! I haven’t looked at the map in detail, but I imagine ensuring you had enough sources took some planning. After a couple weeks in Chaltén, I’m in Calafate and heading south again. Hopefully I’ll find a bit of remoteness and adventure on my way between tourist destinations.

“… WATER sources…”, I meant to write. Always read before hitting “submit”!