| Crossing the Central Darran Mountains |

In mid March of this year I had a window of opportunity for a week-long trip to one of my favourite regions on earth; Fiordland, and in particular, the Darran Mountains. There was a time, a few years back, when I used to venture to these remote mountains relatively frequently, but with work and life commitments and the pursuit of other interests, my adventures there have become fewer. While I never felt homesick as such during our nearly four years cycling in the Americas (2016–2020), I did think of ‘the Darrans’ often and how trips there have become an enriching and important part of my life. So returning there this summer was one of my main priorities since we arrived back in Aotearoa last year.

It’s been a while since I’ve published a blog post about climbing on here, and I know many of the more recent visitors to this blog read it for the cycling content, so if this doesn’t interest you, please hang in there! We have a few content ideas to get people excited about bikepacking overseas again, once the Covid constraints relax, as well as more equipment and route info in the pipeline. So stay tuned.

The northern Fiordland mountains have qualities that make them unique in New Zealand and the world. The Darrans are a narrow range of steep, rocky, partially glaciated peaks jutting up boldly between the Cleddau and Hollyford Valleys of Fiordland. They’re the dripping walls of vegetated granitic rock, complicated craggy ridges and cloud swallowed apexes that thousands of tourists drive past daily during peak season on the Milford Road, but few actually see much of. Their sheer vertical relief and close proximity to the Tasman Sea means rainfall in this region is among the highest on the planet. High precipitation means an abundance of vegetation which clings somehow to the steep lower slopes of the ranges. Thick beech forest, deep moss, flax and alpine scrub sprawl over the lower mountainsides. As you gain height this gives way to perplexingly steep snow grass slopes and finally the glacier plucked and rainfall buffed upper pyramids of the peaks, which yield some incredibly good rock climbing and scrambling and see few visitors.

The combination of fiords, glaciers, herbage festooned cliffs and slender waterfalls that pour from the glacier carved valley sides lend the region a unique aura that some describe as primal. It’s the sort of complex alpine environment that you can gape at in awe for hours, as you try to pick out the details and dimensions of a place in which you feel very small. It’s a place that climbers can both revere and fear at the same time, partly because information about the region is spartan. The guidebook only gives so much away, and many of the region’s secrets are locked up in the minds of those few who frequent the range. Just approaching climbs here can be as much of an adventure as the climb itself, and it can take time to find your ‘Darrans feet’ and to learn to read the terrain.

The plan for this journey, along with companions Tom Riley and Ruari Macfarlane, was to access the Central Darrans from the Lower Hollyford Valley via Glacier Creek, the Donne Glacier Lake and Turners Pass. We’d then traverse over Mt Tarewai, down to Lake Turner, up to Turner’s Eyrie (rock bivouac) and then exit the range via Pakihaukea Pass and Tutoko Valley out to the Cleddau Valley/Milford Road.

While a few parties get into the Central Darrans each summer, Glacier Creek is very infrequently visited (I suspect only every few years) and we could only find one written account from a Tararua Tramping Club expedition there in the 1950s. It was used as an access route for early ascents of Mount Tutoko (Fiordland’s highest peak) and Mount Madeline, back when the glaciers would have been significantly deeper and more widespread, making travel easier. We happened to talk to Dr Dick Price the evening we arrived at Homer Hut (the climber’s base lodge) and he told us of venturing in there in the 70s and 80s, but made it no further than the bushline. The Darrans guidebook reports that Dave Hiddlestone and Anna Gillooly visited in to the Donne Glacier Lake in January 2001, discovering a good bivvy rock there. Richard Thompson descended (solo) from Turners Pass via Glacier Creek earlier this year, and it was him who suggested to us to go in this way on this trip.

We hoped to make efficient time of the mountain travel so that we’d have time for some climbing too and hoped to bag a summit or two.

We set out with six days food from the Lower Hollyford Valley, following the road and track for 12km down to Hidden Falls Hut, where we’d deal with challenge number one, crossing the Hollyford River. The above view is looking up towards Mounts Tuhawaiki and Revelation above Moraine Creek, from the Lower Hollyford.

The Lower Hollyford was seriously affected by heavy rain, floods and landslides last year, which in places have inundated the valley with rocks and gravel, killing a lot of forest. The road is still under repair.

We were lucky to have arrived in the middle of a huge high pressure system that looked as if it was going to hang around a few more days. So most days the skies looked like this. Temps were mild and the wind light the entire time.

With no rainfall in past days, the rivers were also very low, which simplified crossing the Hollyford. Often this broad and swift river requires a swim, but after sussing out a line, we were able to cross with the three of us linked together comfortably enough. We crossed immediately west of Hidden Falls Hut, after a late lunch there.

We then bush bashed, sometimes following deer trails, a bit over 3km NW to join Glacier Creek ~1km upstream of its confluence with the Hollyford. That was relatively fast and straightforward travel through reasonably open bush. Once we reached Glacier Creek we travelled up the bed until it became too bouldery and then spent most of our time in the bush on the true left (TL).

Just before a side stream enters Glacier Creek on the TL we left the creek and climbed up an old bush covered boulder fan. This merges into a steep spur (marked in the guidebook) which we generally followed the apex of up towards the bush line. Travel through here was generally pretty good and quite fast without much forest understory, but very physical with 6-day packs on.

As with much Darrans bush travel to the bush line, the ridge eventually bluffed out and we were forced to zig zag around a bit on very steep scrub and thickly bush covered terrain to find the weakness that would provide access to the upper slopes. Some vigorous flax and tree pulling ensued to get up short rock walls between ledges until the angle eased off.

We broke out on to the tops just before dark and camped in the tussock on a small spur. A perfect site with water from a small stream not far away. Ruari slept under a fly and Tom and I in our bivvy bags.

We were away early the next morning in warm sunshine. The nature of the terrain, with cliffs and deep stream clefts forced constant route finding as we picked our way up a spur and across a gully to the slopes below Pt 1744. That’s the Hollyford Valley down below Tom. Our camp was in the tussock just before the edge of the bush.

At about the 1400m contour we climbed steeply up to the ‘rocky peak’ described in the Darrans guidebook. It’s a tiny outlier knob ~1km SE of Pt 1744, not much more than a rocky bump on the ridge.

Reaching that ridge was the point of the big reveal though, as a stunning view of the Donne Glacier Lake and the NE aspects of Tutoko and Madeline came in to view. It’s an amazing place; remote, peaceful and untouched. For a sense of scale, it’s over 1400 vertical metres from the lake to the summit of Mount Tutoko (2723m) in the centre of the photo. Turners Pass is just behind the rock ridge on the extreme left. Turner apparently describes in his account of descending the pass, that his party descended a straightforward snow couloir right onto the glacier. That’s very hard to imagine now.

We descended to the glacier polished slabs of the lake outlet and lunched in the sun, absorbing the amazing views and figuring out how to attack the next section to reach Turners Pass on the north flank of Mt Madeline.

Looking back at the ‘rocky peak’ and our route down to the outlet.

After lunch we pushed on, eager to get as close to the pass as we could, and knowing that the route finding would not be straightforward.

While we were on the rocky knob we’d picked out a line to reach a possible camp site on rock slabs below Madeline. The challenge with this sort of travel is to pick the weaknesses and least steep sections between rock slabs, cliffs and vertiginous belts of snow grass. It worked out well and we stopped to camp near the base of a prominent rock spur (red dot), sheltered from ice avalanches from the glacier above.

Looking back at the lake outlet…

…and above as we neared the end of the westward sidle beneath the glacier. The following morning we followed the leftward-rising ramp in this photo that passes beneath the prominent pyramid on the left to gain rock ribs and then the glacier.

It was another calm and mild evening under a clear sky. That’s Alice Peak (2155m). The wall on its left becomes Tutoko Knob (out of frame).

As with the previous morning we had an early start – waking in the dark and using our head torches for the first half hour or so of mountain travel. We had to pass beneath the threatening ice cliffs, so both going early and moving very quickly were key for safety. In this photo Tom’s on the leftward rising ramp I mentioned earlier.

Once out of danger we slowed down and absorbed our surroundings more. Early light was creeping into the Donne and revealing detail and colour in the landscape. Again the day was calm and warm.

We crossed the rising ramp and then scrambled and soloed up steep but featured rock ribs to gain the unnamed (on the topomap at least) glacier that wraps around the NE slopes of Madeline.

Looking up towards the summit ridge of Madeline (on left). We crossed the glacier from left to right.

The glacier was split with a deep and wide series of crevasses that ran right to the cliff line.

So we gained a rock ledge which we traversed along and then down climbed from for a few metres to find an abseil anchor.

A 60m rappel got us downslope of the crevasses and back on easy snow slopes and scree which we could sidle to Turners Pass. Ruari had a nifty device called a Beal Escaper that lets you abseil the full length of a single rope and still retrieve the rope. Just eight big tugs or so and down tumbles your rope!

Looking from the ledge down onto the glacier we’d traversed and beyond to the Hollyford Valley and Lake Alabaster.

The classic South East Ridge of Mount Tutoko was looking pretty good too.

We had lunch at Turners Pass and then impulsively decided to nip up to the summit of Madeline (neither Rory nor I had been up there before). We’d started the journey at 100m above sea level and only a bit over 400m remained to the 2536m summit, so it seemed silly to miss the opportunity.

In a place as steep and complicated as the Darrans, just a couple of hundred vertical metres can make a massive difference when it comes to views. I really enjoyed this perspective looking down on Lake Turner (one of our destinations), with Karetai to the left and Patuki to the right. The next layer of mountains beyond those are the Moraine Creek faces of Sabre and Marian Peaks, Barrier Peak and Barrier Knob. And then behind those, Crosscut and Christina. The dark peak above Barrier Knob might be Pyramid Peak.

And in the other direction the Donne Glacier Lake and Lakes McKerrow and Alabaster.

And beyond Mt Tutoko, the shimmering Tasman Sea.

We could not have had a better day to be up there. The North West Buttress route to the summit from Turners Pass followed steep snow, a rock ridge (scrambling) and then the snowy summit ridge and took roughly 3 hrs return. It was first climbed in 1958.

Back at Turners Pass we sidled around onto the upper Madeline Glacier and descended towards rock slabs above Turners Bivouac.

Looking back the way we’d come. It was a beautiful time of day to be on the glacier.

We stopped and camped on rock slabs once again, just on the edge of the glacier approximately 300 vertical metres above Turners Biv. That’s the summit of Madeline top right of the photo. Our route to the summit followed the left skyline, from the upper glacial shelf that’s level with the Moon.

Once again we sat on the rock slabs, drinking tea, cooking and discussing the day past and plans ahead. When it came time to sleep we rolled out our bivvy bags and slept under the stars again. I woke occasionally to the sound of ice avalanches tumbling and cascading off Tutoko’s heavily glaciated south face.

In the morning we were again already moving before it was light, sidling our way through the numerous whalebacks of glacier polished rock and across patches of névé towards the Milne – Tarewai Col. The plan for the day was to reach Turners Eyrie via Mt Tarewai, Pikipari Pass and Lake Turner.

Climbing over Mt Tarewai from the Milne – Tarewai col is one of the standard access routes to reach Lake Turner and Turners Eyrie, and one of the fastest. Turners Bivouac is one of only two places in the Darrans that helicopter landings are permissible, so by flying in there early in the morning, it’s possible to reach Turners Eyrie the same day.

Most parties will put in a pitch or two from the col to get started and then scramble the rest to the summit. Because we were carrying one 60m rope, we did two ~30m pitches and then scrambled. The Milne – Tarewai Col is an amazing place. For first time visitors, their first glimpse of the Cleft Creek catchment will be through the narrow defile between the two peaks. This feature (the Cleft) continues sharply down slashing through the upper cirque towards its confluence with the creek draining Lake Turner.

Note that the topo map for this part of the range has several mistakes: What’s marked as Tarewai is actually Milne, Mahere is Tarewai and Pakihaukea Pass is Pikipari Pass. The actual Pakihaukea Pass is immediately south of Pt 1927. Waitiri is actually known as Makere (although Mahere is possibly the correct spelling). Pt 1976 is the correct location for Waitiri.

From the summit of Tarewai the view gets even better. That’s Mt Te Wera on the left, the Karetai Col, Karetai Peak, Karetai – Patuki Col and Mt Patuki far right with a broad snowfield and narrow snow couloir leading towards the summit. We descended that couloir after climbing a new route on the mountain the next day.

The descent to Pikipari Pass is a mixture of walking and scrambling, with a couple of very exposed steps, but it’s straightforward. That’s Mt Patuki and Mt Underwood in the background.

From the col we picked our way down rock slabs and then snowgrass, passing under the toe of Makere and sidling around to the Lake Turner outlet. By that time the mist had pushed its way into the upper cirque.

From the outlet we pushed on, sidling above the lake on the route shown here. The route then climbs steep talus towards the Karetai Col and base of Lindsays Ledges before cutting out diagonally right (SW) in the general direction of the Karetai – Patuki Col. That’s Mt Te Wera (north ridge and west ridge) in this photo with Karetai Peak and Karetai – Patuki Col on right.

And finally the Eyrie. This was my second visit and Tom’s second or third. It’s a sensational spot; like an eagle’s nest on the edge of a cliff. To reach it from the talus slopes on Karetai’s west ridge you’re forced to make a committing few steps above a big void before reaching the relative safety of the ledge. It’s no place to be a sleepwalker!

As I mentioned, we’d come in with only one 60m rope and about five pieces of gear. That equipment was solely for access/egress. Our friends Rich Thomson and Rich Turner (who discovered and developed the Eyrie) had a rack and two ropes stored there which we used to climb with the next day.

Water can be collected about 50m east along the ledge, where it trickles down from a patch of névé. By late March there was not much left of the snow patch (and it probably won’t survive long term) so we had to wait a while to fill bottles. Earlier in the season it’s more reliable.

This shot from my 2012 visit with Tom, John and Alan gives a better impression of this amazing location. That’s Patuki in the background with the east ridge descending down towards the viewer. Here’s some photos from that 2012 trip.

The now classic Eyrie view of Tutoko, Madeline, Lake Turner (beneath the cloud) and Te Wera.

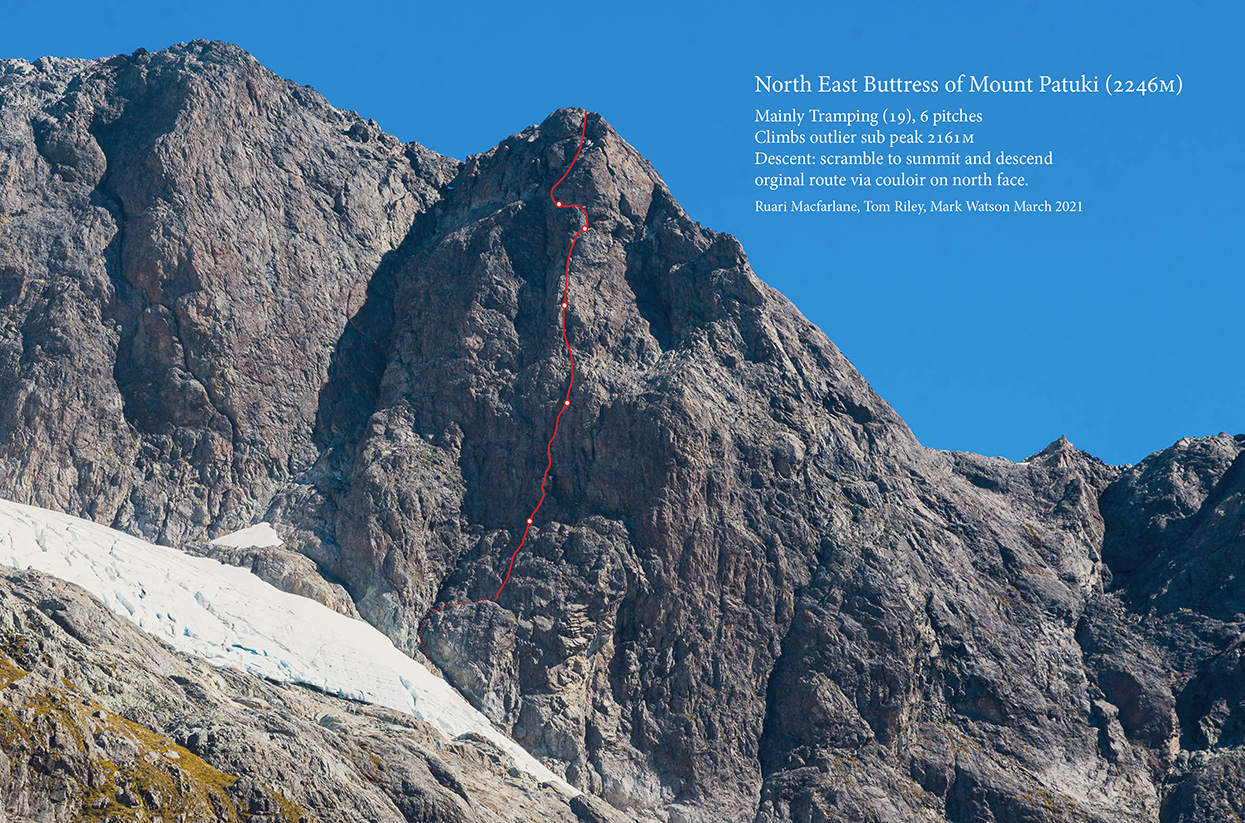

We left early the next day on a day trip to look at an outlier buttress (Pt 2161) on Mt Patuki. This feature has a broad east to north east facing butress and we’d spent some time looking at it on the climb up from Lake Turner.

The approach over convoluted rock slabs (the snow is much faster) took longer than we expected, and then we deliberated for a while over which line to try. But eventually at about 11am got started, soloing up to a good ledge to rope up on and belay from.

We put in six pitches (mostly 50-55m) of good climbing with each pitch having an interesting crux. The hardest of which was 19ish on pitch 5, to clear some steep overlaps. The easier climbing was typically run-out but on the cruxes there was always plenty of good gear.

From the summit of Pt 2161 we scrambled to the summit of Patuki and took in the amazing view before descending the prominent couloir on the NE Face (the first ascent route). We mostly down climbed this unroped on the TL until the rock blanked out and then descended the snow. A 60m rappel was required to clear the bergschrund. From below it looked as if you could also downclimb the rock on the TR of the couloir to a much lower point and possibly avoid the rappel. Rich Thomson told me he’s down climbed the diagonal gully between the Patuki summit and Pt 2161m.

We made it back to the Eyrie just on dark and ate most of the rest of our already low rations in preparation for a big exit day the next day.

Our plan was to exit via a variation on Pakihaukea Pass, which none of us had done before. Several years prior I’d taken a photo of some dotted lines on Rich Turner’s topo map and these were our cue. The idea was to try to nip over the ridge about 500m south of the pass itself (just south of the summit of Waitiri) and then descend immediately joining the south end of the snowfield that’s marked on the topo map (the snowfield no longer exists). We’d then meet the Pakihaukea Pass descent which is sparsely but sufficiently described in the Darrans guide.

So we left very early and crossed back over the snowfields beneath the east face of Patuki as the sun rose.

We down climbed the rock rib we’d used the previous day to access our new route (to bypass a steep and broken section of the névé) and rejoined the snow.

This was our route up onto the ridge just south of Waitiri’s summit.

Looking back at the snowfields we’d crossed beneath Patuki, and the buttress we’d climbed the previous day.

From the ridge we descended carefully down steep scree, between islands of bedrock and patches of snowgrass, until we got onto solid rock slabs which we down climbed until it was possible to walk again. We made it down without an abseil and it was a quick and efficient descent that I’d use again. This is looking back up at the west (Tutoko Valley) side.

We stopped on the sunny slabs and ate most of what was left of our food: in my case two slices of cheese and some chip crumbs. I saved a muesli bar for later because we still had a long way to go.

We wove our way down steep snowgrass, through a short section of scrub and picked up the bush just below the 1000m contour. After a short bush bash we joined a creek bed (which flows north for a while on the map), and then committed to the bush again as the creek turns west and drops away. We bashed though this (relatively quick travel) aiming for the final waterfall that’s mentioned in the guidebook. We got within about 80m of that watercourse before committing to the very steep descent towards the Tutoko. A series of bluffs complicate the descent, but by weaving back and forth we always found a way to keep going down without getting out the rope. Conditions were very dry, meaning the often wet, mossy slabs and gullies were crossable, which gave us more options. The final third involved a few committing bridging moves down between trees and the cliff, or jumping down overhangs onto ledges. I can see why this route has never been popular for access!

Eventually, covered in scratches, sticks and dirt, we popped out in the bed of the creek which curves down to meet the Tutoko River.

The lower part of the watercourse described in the guide book. We descended through the bush to the right.

And finally, the massive Tutoko Valley. You can just see the watercourse and the bush we descended on the far right of the photo.

With the Pakihaukea descent out of the way we relaxed and our thoughts turned to the road, only a couple of hours away, and the promise of hot food and beer at Milford Lodge.

Spectaculaer !

What a place, what a trip! I think I was there just before you! I went from the Tutoko, over Pakihaukea Pass, stayed at the Eyrie on 18th March I think. I was planning to go to Moraine Creek via Lake Adelaide, but saw from Karetai that the Te Puoho Glacier was very crevassed, so went back the way I came. I wasn’t sad to have to repeat that day around the shelves above Lake Turner, pretty awesome views! I camped where that second-to-last creek that you followed South-North on the shelf above the Tutoko went off the edge.

Thanks for the message Joel. Well done doing Pakihaukea twice. Coming up that would have been a good challenge. I had considered going in that way originally too. That’s a shame you could not continue to Moraine Creek, but sounds wise. It’s a section I’d like to do sometime too. And, the ‘position’ of that sidle above the lake is amazing. Such a special place. Good luck with your future trips.

Sorry, via Rainbow Lake.

Fantastic trip Mark, and great photography as always. Can’t quite believe the weather window you caught!

Thanks Richard. Yes, we were very lucky, that’s for sure. And that was only the second half of the window! Wish I’d been down there a bit earlier 😉

The Darrans are amazing. We pack rafted the Hollyford-Pyke this summer and looked up at the first parts of your route. I was awed by the gorgeous and rugged mountains. Your photos and story are brilliant. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks Chris, yes I see you & family have been up to some great adventures! Love it.

Sacrificing kai to bring along the SLR was so worth it….for all of us at least. Clearly TWP was good fitness for a heavy pack in steep terrain. Stunning phots of perhaps the most beautiful mountains on Earth, very inspiring as always Mark. And thanks for fantastic beta on routes mate. Tino pai bro

Haha, thank you Justin. Classic last-second rethink of food saw a couple of items turfed! Regretted that. I think I underestimated how many calories your brain burns when you’re constantly micro navigating in that terrain! But yes, so glad to have my camera.

Wow! Wow! Wow!

Thanks for sharing; blog & stunning photos. Shame that the glacial retreats are occuring so quickly

Thanks Alastair! Yes they’re disappearing devastatingly fast. Peru and Bolivia were in a very sorry state too.

Hi Mark,

Glad to read your blog, this is an extraordinary mountain trip. I can see it is very challenging for climbing and hiking along the way. I still remember that you and I went to the Darrans in 2015 together. Thanks for helping me to have such unforgettable experience. Hope someday we can go to the Darrans together again. All the best!

Yan

Hi Yan, thank you. Glad you enjoyed the read. Yes I have great memories of the trip with you. Maybe now with the Trans-Tasman bubble we can plan another one! I hope your photography and projects are going well.

Cheers,

Mark.

brings it all back and makes me smile. stunning photographs. Thanks Mark

Glad you enjoyed them Ruari. Thanks for an amazing trip!

Two slices of cheese and some chip crumbs 😀 Always the connoisseur. Awesome adventure and great photos!

Haha, you know the story Felix! It would be great to show you this place someday. I hope all is going ok for you guys.

Fantastic Mark! Love your writing style too. Such cool shots, stunning places and an inspired route. You guys got the trifecta with the weather as well.

Jealous!!

Cheers, Geoff

Nice one guys, great adventure. Looks like you weren’t too far from the ok bivvy rock we found and named ‘Hip’s Hollow’ on the way up from the Hollyford, near the top lake. Yours in adventure, Anna G

Thanks Anna,

Back when I was editing The Climber I remember publishing a news item about your trip in there, or perhaps just the guidebook, I don’t recall exactly, but I was aware of it. We were feeling some pressure that day to keep moving so we didn’t explore the biv, but it looks like a great spot. I think Richard Thomson might have checked it out. Anyway – fantastic area!

Tremendous trip, wonderful photography!

Thanks – it was a good one!

Holy f*ck