| Traversing the Chilean/Argentine Puna, Part I |

The Ruta de los Seis Miles is a 1300km-long remote bikepacking route that traverses the length of the Central Andean Dry Puna region of Chile and Argentina. With an average elevation over 4000m the puna region is defined by a long chain of volcanoes and the barren high altitude Atacama Desert.

Water is scarce, human habitation is even scarcer and often the roads are no more than two tyre tracks through sandy volcanic soil. Combined with savage afternoon winds and exposed country this can make for very difficult riding conditions. The ‘Seis Miles’ (Six Thousanders) represents the several volcanoes over 6000m in elevation that the route weaves its way between, which are among the highest mountains in the western hemisphere and the highest volcanoes in the world.

The legendary Lagunas Route, the Volcan Ticsani region of Camino del Puma and the Ruta de la Vicuñas all feature aspects of the Seis Miles experience, but even these notable bikepacking routes do not come close to matching the sense of isolation, physical and mental challenge, or astonishing beauty of the large swathe of Argentine/Chilean high puna traversed by Seis Miles. It’s a place where you feel incredibly small and exposed to the indifference of nature. A handful of cyclists have made expeditions into this region, but it wasn’t until 2018 that Finnish bikepacker Taneli Roininen ventured onto the sandy roads and high passes of this immense landscape and wrote up his journey as a route contribution for bikepacking.com

For us it was a route that we had been anticipating and building up to for a long time. Many other sections of our ride during the past few months have felt like small preludes and I have often found myself thinking ‘how would this riding feel if I had 13 litres of water on my bike and two weeks food?’

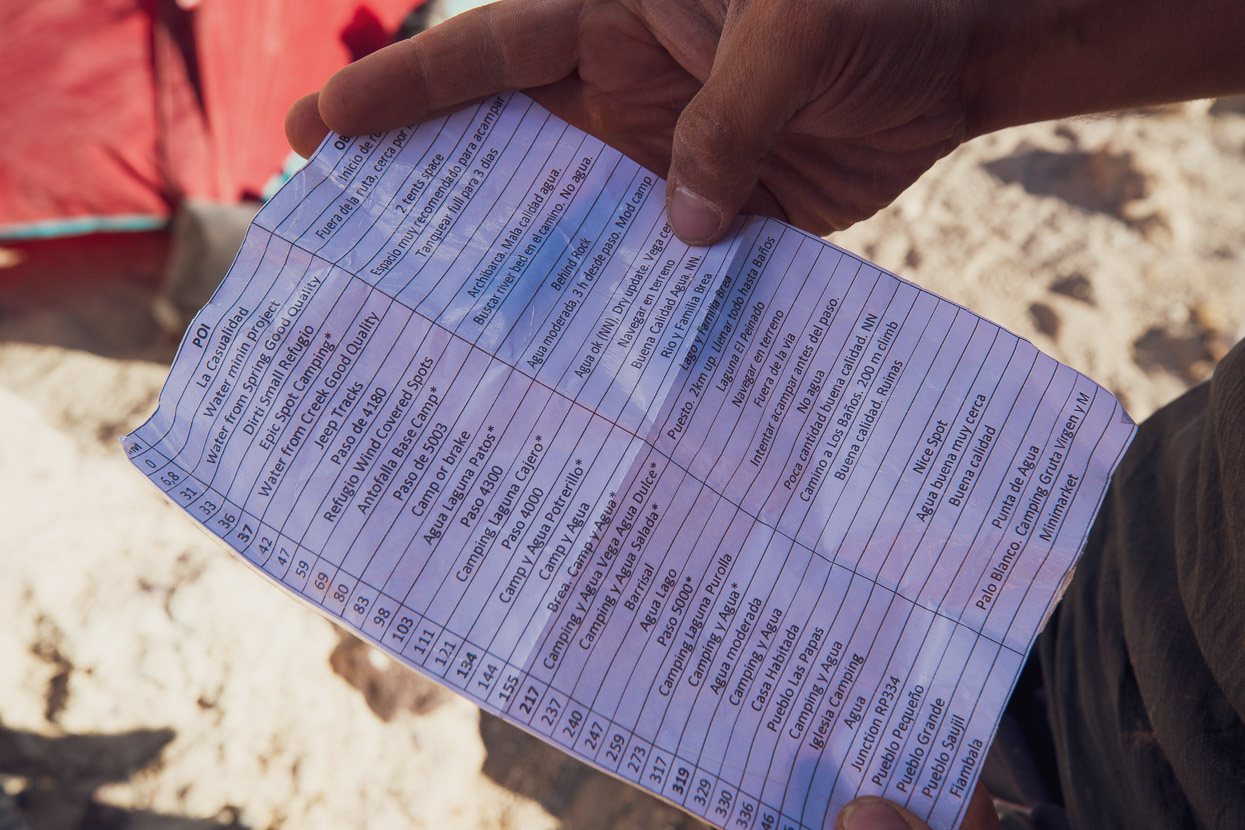

The Seis Miles route is split into two sections; the Norte, from San Pedro de Atacama, Chile to Fiambalá, Argentina and the Sur, from Fiambalá to Guandacol. The northern section is the remotest and hardest, requiring 16-20 days food for its 784km length. There are no opportunities for resupply. The southern section is slightly shorter at 526km and is slightly less remote, requiring 8-12 days food.

We left San Pedro de Atacama to begin the northern section on the 2nd December 2019 with 18 days food. We were in the company of German bikepacker Felix Blaß, with whom we’d cycled/climbed Volcan Uturuncu and completed the final part of the Lagunas Route with in the prior fortnight.

This blog post is a departure from our usual style and is more of a trip report, with detail intended for other cyclists venturing into the region. My apologies if this bores some of you, but the photos alone of this enigmatic landscape will hold your attention I hope.

There is a summary of our thoughts about equipment and planning at the end of the post.

Days 1–3, San Pedro de Atacama to Monturaqui Meteorite Crater

We took it very easy the first two days on the road, just riding half days on the mostly paved route that leads along the edge of the Salar de Atacama towards the beginning of the dirt proper and the long gradual climb towards Paso Socompa. We spent the first night in Tocanao, where there are a couple of basic hospedajes and restaurants. There is no organised camping here, although there are pools above the town you can visit during the day.

The second day was an easy spin on pavement to Peine, which is smaller than Tocanao. But you can get basic meals and there is good camping and shade at the pools (small entry fee). Peine was the last opportunity to buy anything until we reached Punta de Agua some 700km and 15 days away, so we picked up some last minute items, such as cheese and salami from the tiendas there.

Early on the third day we left the paved road on the edge of the Salar de Atacama finally, climbing gently, at first, onto the edge of the volcanic steppe. An endless cordillera of volcanoes formed the skyline to the east. After 37km we cached most of our food under some rocks and detoured off the route roughly 12km (400 vertical metres) to visit the Monturaqui Meteorite Crater, which is a prominent 450m wide impact crater, clearly visible in satellite photos. It’s thought to be roughly 1 million years old and created by an iron meteorite. We camped comfortably inside the crater, but it’s still exposed to afternoon winds. There are great views of the volcanic chain and Salar de Atacama from the site, which is well worth visiting in itself.

Days 4–5, Monturaqui Meteorite Crater to Vega Socompa

We rejoined the main route by backtracking (mostly downhill) and then reached the waypoint labelled ‘Water from Leaking Pipe’ and ‘Camping behind House’. We weren’t expecting much at this location except to restock water but it’s actually an estacion de bomberos (fire & medical) to support a nearby mining operation. The staff were extremely generous and gave us handfuls of fresh fruit, large bottles of water, fruit juice, instant soups and yoghurt and invited us to eat lunch in their station, supplying us coffee and as much bread as we wanted.

Back on the route we rode a long afternoon, joined the railway tracks finally (generally really good riding with amazing views) and then bivvied inside the abandoned railway car at the ruins of Estacion Negrillar. This is a stunning site, with an unforgettable view towards the volcanoes and over the lower puna.

More railway followed in the morning until we turned off and reached the good water supply at Monturaqui and then made the long, but gradual, climb up to Paso Socompa and the border. The Chilean exit took about 30 minutes to process the three of us. Only 56 other people had crossed in the past year. The Argentine entry was more relaxed and we were offered a refugio to eat lunch in and given hot water while they spend about an hour processing our passports. The Argentinians offered us the refugio for the night, but we wanted to carry on down to the iglesia at the abandoned estancia at Vega Socompa, which was well worth it.

Socompa Pass is the gateway to a region that can only be described as otherworldly, a dry, barren and rugged landscape of grey, red, orange and yellow streaked mountains. A place formed of volcanic eruptions and hewn by the relentless action of glaciers. Where there is vegetation, it’s hardy, thorny and unfriendly, resistant to the appetites of the small herds of roaming vicuñas. How it survives is a mystery to me, but I guess it’s the same way we will; by conserving water. Even the rock is not resistant to the ravages of the wind. It’s pitted and wind worn and in many places ventifacts litter the ground.

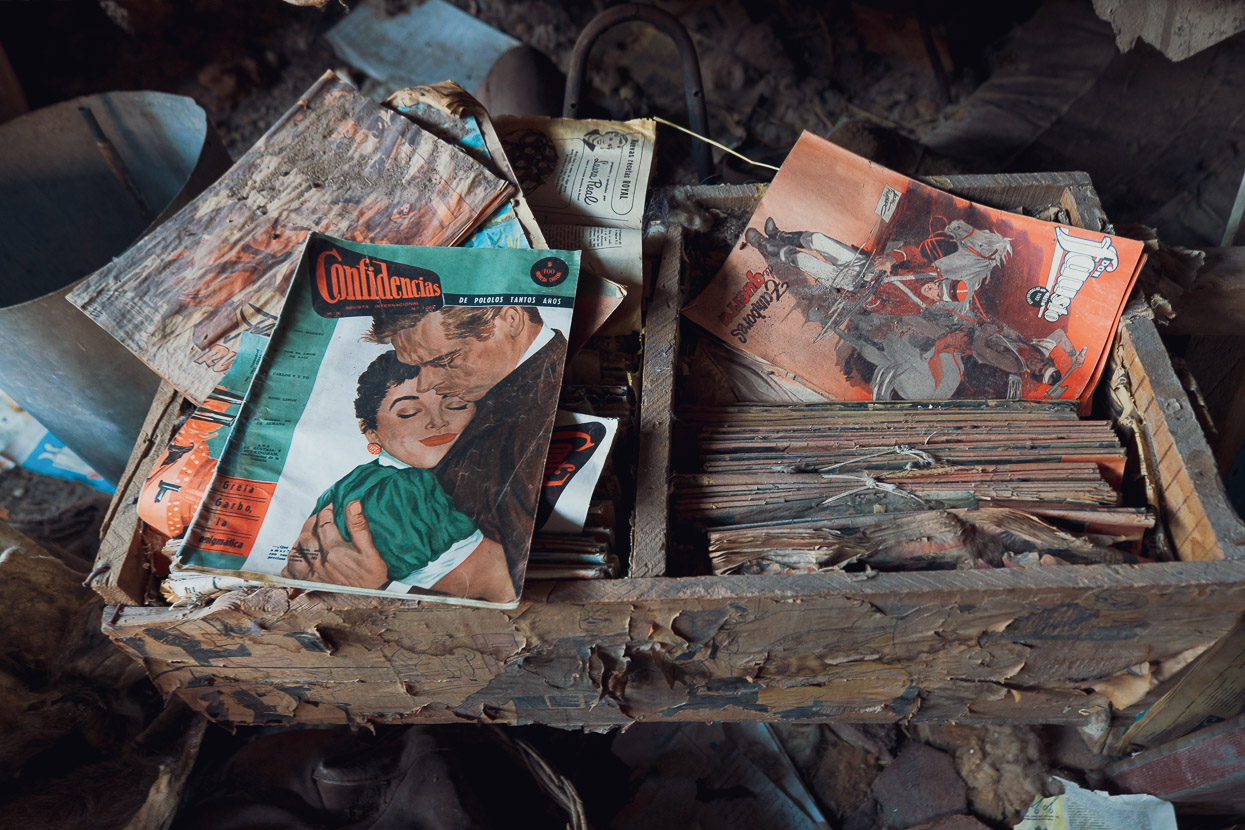

The iglesia at Vega Socompa is a very pleasant spot (if not a bit dusty) to spend the night in out of the wind, and the spring water is good quality. Behind the iglesia is a mud brick compound that must have been a family estancia for many years. When it was abandoned I don’t know, but inside there are still family photos on the walls, books on the shelves and clothes in the drawers. The place is an incredible time capsule, with magazines from the 1940s and old newspapers stored away, along with all manner of household goods, furniture and tools.

Now that we were finally over Socompa Pass it felt as if Seis Miles was really beginning as we left the iglesia with 13 litres of water each (2.5 days worth). With nearly all our food still on board the bikes were the heaviest they would ever be at this point and it was reassuring that from here they could only get lighter.

Days 6–8, Vega Socompa to Mina La Casualidad

By midday on the first day out of Vega Socompa the much feared wind that we had read such bad reports about made itself known and we battled strong head and side winds from about 11am as we climbed the first big pass. The landscape throughout the day was stunning. Both the climb and the descent, albeit sometimes rough, were 100% rideable. Because we had in mind to make a detour to explore Mina Julia (above Mina La Casualidad), we took the waypointed shortcut down to Salar de Llullaillaco, which avoids the second pass, allowing us sufficient water and energy for the 690m climb up to Mina Julia the next day. This proved a worthwhile strategy and we felt we gained more from seeing the amazing landscape at Mina Julia than the pass we skipped.

Note that the route waypoint ‘Shortcut Avoiding the Climb’ is in the wrong place and should be at salar-level at an altitude of 3760m. The route to the salar was 99% rideable for us on 3-inch tyres, although it is very sandy and in some places rock-littered. We chose to take a direct cross-country line to the salar as the route is nearly all descending, but we did cross a sandy doubletrack at one point. We weren’t sure where it led so stuck to a direct bearing for the salar. There is a very good doubletrack right along the salar edge, that sometimes climbs steeply over small headlands.

That night we struggled to find any wind protection for camping and ended up with partial cover behind a slope on the edge of salar after riding for an extra hour looking for a suitable place. But reliably the wind had all but abated by about 10pm (this was the pattern most days with the wind starting between 11am-2pm and ceasing almost totally around 10-11pm).

There is not much to report from the next day as we rode the last of the salar-edge, rejoined the route, followed fun rolling roads for a time and then made the steady but not steep climb on a good surface to the pass above Mina La Casualidad. We camped with partial shelter from a small embankment near the old mining cableway (about a kilometre up the Mina Julia road) after spending nearly two hours exploring volcanic outcrops for a better camp site. It’s an interesting place as the ground between the wind eroded ignimbrite outcrops is littered with many thousands of small ventifacts.

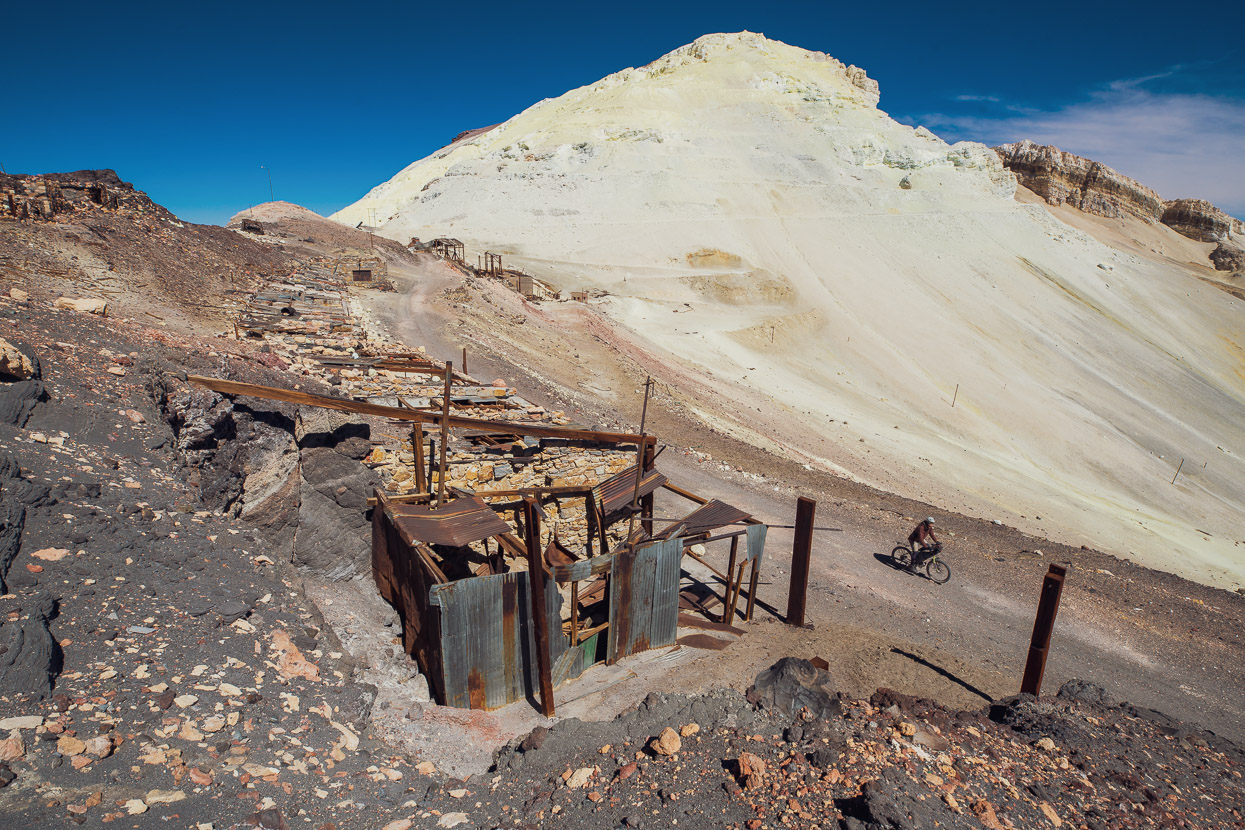

The following morning Felix and I (Mark) left just before 7am to make the 13.5km/690m climb up to Mina Julia. A steady breeze still blew and it was -8c when we started riding. The road is good, with little sand. The detour was absolutely worthwhile, with incredible views from the pass at the top across very remote and colourful puna into Chile, and the scenery on the climb alone was spectacular. Mina Julia (abandoned) was the sulphur source for a refining operation at Mina La Casualidad (some 1200 vertical metres below) and like La Casualidad was shut down in 1979. These days the site is littered with abandoned structures, workers quarters and rusting machinery. Sulphur was carried by cableway 15km down to Mina La Casualidad.

Back at camp around 11am we packed up and rode the downhill to Mina La Casualidad. The iglesia at this ghost town has become a de facto refugio over the years and we were glad to have shelter from the wind and space to spread out our gear and do a food stocktake. The guest book in the iglesia records a few visits from cyclists as well as a few other tourists and former workers and their families from the mine who return each year for reunions. Later in the afternoon we walked around the old town and explored the decaying machinery, towers and tanks where the sulphur was processed and refined, as well as the homes and offices of the up to 3000 former workers that the town supported. Virtually anything of value has been stripped from the town now, including floor and wall tiles and most of the fittings. We saw the two stray dogs we’d heard about from other cyclists, but they were not interested in us or our food.

Days 9–12, Mina La Casualidad to Brea Summer Farm

From Mina La Casualidad we dropped down to the salar, which was easy riding with stunning views, and then entered a broad and sandy valley filled with rock mesas and cliffs. This led past a spring (good water) and a stream (even better water) to one of the best campsites of the route: a mostly wind sheltered ‘ledge’ among boulders under a cliff which provides shade in the heat of the day (POI Epic Spot to Camp). The camp gets early sun too. It was about one hour after we arrived here that our five Colombian friends (see previous posts) also turned up, having skipped the northern part of the route and joined at Mina La Casualidad via Tolar Grande.

It was really good to see the Colombians (José x2, Sergio, Diego & Mario) and hard to believe that on such a remote route there were now eight cyclists in the same place. We ended up sharing campsites for the rest of the ride, except for one night, which made what was expected to be a very solitary experience a pleasantly social one as we shared stories from the road each night and helped each other repair gear failures and punctures.

From the cliffside campsite the Ruta de los Seis Miles starts to get harder, because the roads become considerably more sandy and there are two high passes. The harder riding is compounded by the need to once again carry 2.5 days of water to get you through to the oasis at Potrerillo Creek.

Shortly after leaving the cliffside camp the route passes a small salar on its right and then the route goes about 200 vertical metres up a very steep and sandy unrideable track. This is recommended only as a northbound line. Shortly before that route steepens, there is a sandy, but 100% rideable track that cuts off sharply to the right and then cuts back left, rejoining the route about 200m higher. This was a very good choice.

The rest of the climb to the pass was tough, but nearly all rideable with low pressures. The descent from the pass was all rideable and a lot of fun as it ‘rollercoasters’ down towards the salar. Following a tip from our friends Guillaume & Donia who rode the route the previous December, we rode the hard bed of the shallow arroyo that parallels the road, rather than the sandy road for most (about 6km) of the climb towards Antofalla Basecamp.

The ‘basecamp’ was a disappointment. We were hoping for shelter from the strong afternoon wind but there is only partial cover from some rock outcrops. There are no stonewalls or oft-used tent sites (in fact when we arrived there was only evidence of a small spot for one tent ever being used). If you go a little further along the lee (south side) of the ridge past the waypoint there is a reasonable space for two tents & good cooking shelter at the base of a 2m outcrop.

From Antofalla Basecamp it’s a steady and hard climb on a very sandy road to the first 5000m pass of the route. It’s not steep until the top, but the surface and altitude makes it very draining work. With low pressures it’s possible to ride it all but I put my foot down many times to rest and a couple of times pushed across to a different set of tyre tracks in hope of better traction. We noted that even if you are totally maxed, concentrating hard to ride the surface and stopping often, you still use less energy than pushing. With less experience on sandy roads, most of the Colombians walked a lot of the climb.

Early that morning one of the mounting stays on my aluminium rack broke (rack-seat collar stay) but we were able to repair it with two small hose clamps and a splint made from a section of stove windshield.

The descent from the pass was 100% rideable for us, but once again it was vital to drop our tyre pressures really low when the sand got bad lower down, closer to the salar. We took a short detour off the route, sidling above the salar on a good double track, which saved a bit of climbing. The main climb to the saddle between the salar and the abandoned refugio is relatively short but the surface is very soft and stony so with tired legs we all walked some of it. The descent to the abandoned refugio and laguna is fun and very fast. We had a surplus of water so did not bother to get any from the vega, but it did not look easy to collect as the water is extremely shallow and had a lot of algae in it. Our rule of thumb was generally to carry enough water not for the next water source, but the one after that if there was any doubt as to the water source’s quality/reliability. The small refugio building (full of animal poo) provides good shelter from the westerly wind and we camped outside it.

As far as world class riding and views go, the next section as far as Las Chacra (Brea winter farm) is hard to beat. There is a small climb up to the ‘Dune of Doom’ which we sidled down for a while, riding a vague single track, and then plunged down towards its base. This monster would be a formidable challenge going in the other direction! After that the route descends through a remarkable landscape that reminded us of mountain biking in Moab, USA. It’s a short detour to visit Las Chacra, near the entrance to a narrow canyon. We visited out of interest, not necessity, but appreciated the shady trees and running water of this amazing spot for a lunch break. The Brea Family have farmed the region in total isolation for decades and use this spot as a sheltered winter farm, while their summer base is a little further down the road.

We arrived at the summer farm to find the Colombians had been well received by the Breas and were tucking into the remains of a freshly cooked sheep. We were given the same treatment and sat down to the last of the animal, including its head and other gory looking leftovers. The Breas also gave us a some cans of beer to share and some soft drink. Generously they opened their small home to us totally, so we finally got a chance to wash bodies and clothes, and relax sitting around their kitchen table. Their 4WD is a recent acquisition and previously the family travelled by mule to the nearest village about 18 hours away. We offered them a small donation for their hospitality when we left which was gratefully accepted.

Also enjoying some Brea Family care was a young llama which had been rescued after a puma killed its mother. We’d seen what we had assumed to be puma tracks earlier in the day so they were very interested to know where.

Overall we’d planned to include two half days of rest into our Seis Miles Norte ride and we spent them at Mina La Casualidad and that afternoon with the Brea Family.

Days 13–16, Brea Farm to Termas Los Baños

Shortly after leaving the Brea Farm the road kicks up into a tough 400m climb that is both sandy and steep in places (but rideable), followed by an incredible fast descent to the Boulevard of Broken Culo as the Salar de Antofalla has been affectionately dubbed by Seis Miles rider Kai Larsen. This arse-beating marathon is the Paris-Roubaix stage of the Seis Miles Norte and for us it was heads down, pedalling hard for many hours as we tried to find the smoothest line along the rough road of lumpy, crushed salt and deep huecos (which can take you out if you’re not constantly watchful). The road improves from time to time but is generally bad and slow for 33km until it climbs away from the salar just before the lava field. Along with the bad surface, the second half of the ride was into a gusty headwind.

We noted that the lava field had really good sheltered camping as we passed through it, but wanted to camp closer to the turnoff for the hike up to the crucial spring at the abandoned estancia at Agua Dulce. So we skipped the good sites and in the end we picked a small embayment just before the road crosses saline streams at the southern end of the salar. It seemed relatively sheltered for the first few moments after we stopped, but as we tried to pitch the tents the wind seemed to change and strengthen. With that and the extremely hard salar surface Felix could not pitch his tarp tent. We all huddled behind mine and Hana’s tent to cook dinner and then at 1945hrs left to walk up to Agua Dulce to collect water.

While this strategic move did save us time and energy for the following morning, it was more of a mission than we expected and took two and a half hours return. The wind was almost blowing us off our feet on the exposed walk up to the valley where the spring is located and then we had to walk about 15 minutes further up the valley than the marked waypoint to actually find running water. It was a grovel in the dark and we were thankful for the GPS for the return walk (still in a gale) on the moonless night. We all filled to capacity at the spring to cover a further 2.5 days riding. By the time we got back down to the lava-edge the wind had dropped and Felix could get his tent pitched.

The late night and extra exercise compounded our tiredness the following morning. We’d been riding for two weeks now without a day off and were starting to feel it. For the first time in my life I started to appreciate how those Grand Tour riders must feel two thirds of the way into the Tour de France.

A feared obstacle on the way to Volcan Peinado is a sometimes steep grovel up and over a ‘sandy funnel’ between the lava field and steep slopes to the west. Again, with aggressively soft tyres this was nearly all rideable, but we felt exhausted and slow the whole morning. Once the funnel is over the vista down to Laguna del Peinado with the mountain behind is one of the best views of the route.

We ate a long lunch at the small undisturbed thermal pool (please don’t swim in it) by the laguna and brewed coffee in hope of eking some more energy out of our bodies. The afternoon went better after that and we rode a pleasant, sometimes sandy, two hours further past more lava and amazing mountainsides to reach the edge of the lava flow 1km before the road turns sharply east to climb the 4990m pass. We found sheltered camping in an arroyo right by the edge of the lava and it was a fantastic place to spend the night, with nice light morning and evening.

Day 15 was to be our last hard day on the route, and although our legs felt as if gravity had doubled overnight, we were blessed with a vigorous tailwind all morning which made the 1000m climb from the lava field to the pass easier. About 50% of the climb is on soft sand, but we managed to ride it all. The Colombians had camped two hours behind us the previous evening and as we neared the pass a very fast moving ‘Superman’ José (Colombian climbers!) caught us. We were reunited with the rest of the Colombians later that afternoon after the 1000m descent to the amazing salar and pumice-field at Laguna Purolla, where we bivvied behind some rock walls (waypointed) on the edge of yet another massive lava flow. We’d finished the day relatively early, but were still very tired, so enjoyed a bit of extra rest despite a gale wind all afternoon.

The next day was slower going than we expected, but made for a stunning ride on generally good surfaces all the way to the Termas Los Baños (2km off route). The route crosses a gigantic pumice field and a volcanic crater before gradually starting to drop off the puna back into a land of grasses, flowers and scrubland. Arriving at the termas and hanging out with our Colombian friends in the hot pool was a fantastic conclusion to the hardest part of the route and the pools are an incredible treat to look forward to.

Days 17–18, Termas Los Baños to Fiambalá

A long and rocky descent (I cut my tyre and plugged it successfully with a tyre plug) led down to our first village in two and a half weeks at Las Papas. There’s little to buy here, but a family prepared coffee and bread for us when we asked and it was nice to see people again. From there out to the next village at Punta de Agua the road follows the canyon downstream and crosses the river 80 times. The crossings are all ridable and for the first hour it was a lot of fun, but it’s a long way down the valley and we were all very grateful to hit the smoother road just before Punta de Agua. This village has tiendas so we were quick to rip into bottles of beer, tinned peaches, pan dulce and watermelon before the last leg into Palo Blanco. In Palo Blanco we hit the tienda again for fresh bread, cheese and olives, beer and lemonade before finding a restaurant for a big meal. We camped that night by some ruins on the edge of the football field. In the morning a nearby household sent their two youngest boys out to gift us a big loaf of bread.

Day 18 was a pleasant formality with an easy ride on pavement into Fiambalá 48km away, where once again we raided the tienda for ice creams and soft drink before moving onto a restaurant for a late lunch. It was the 19th December so we settled into the San Pedro Hostel (highly recommended) to rest, do a bunch of gear maintenance, resupply for the southern leg and prepare for a Christmas feast with the hostel’s staff and friends.

Some further thoughts

The Ruta de los Seis Miles Norte was for us a thoroughly enjoyable, if not very challenging at times, ride through a region that is like nothing we had witnessed before. It’s an extremely special experience. We were blessed with good weather, with not a single storm during our time on the route, and generally quite mild nights, for the altitude. There were perhaps only 4-5 nights where the temperature fell below zero C, and during the day we often rode in t-shirts or singlets until strong afternoon winds brought a bit of wind chill. Overall the wind was annoying at times in the afternoon but we only had three camps that were unpleasantly exposed and generally the wind was not as madness-inducing as we were expecting. Sometimes it was even to our benefit with strong tailwinds on climbs.

I think our formula led to it being a good experience, in part due to the following factors:

• We were generous with our food allowance. The riding is not hard enough that a spartan diet is crucial to make progress easier, and I think in the end a minimal food regime might just mean less energy and wishing the route was over as soon as possible. We all finished with about a day’s food left. A bit of ‘fat in the system’ is a sensible move in case you fall sick on the route or are delayed for whatever reason and have to stay put for a day or more. On mine and Hana’s part freeze dried dinners helped keep our weight lower and minimised fuel requirements.

• We were realistic with our daily goals. Our MO was to wake early (around 0540) and ride days of between 4-7 hours moving time. 4 hours might sound short, but when the roads are sandy and at high altitude and any forward progress is a big effort, it can be enough to leave you pretty tired. We preferred to start early and finish early because this gave us the calmest part of the day to make the majority of our progress (usually).

• We had enough food to take two half days of rest. These were crucial to recover a bit of energy and also to give us time to appreciate where we were. It’s not a place you want to rush through.

• We did not make a daily plan before starting. As they say in the military, ‘no plan lasts the first five minutes of combat’ so we didn’t want to waste time with a plan that might fall apart after two days due to something unforseen such as a mechanical or a bad storm. Instead we structured the route in blocks (as we went), based around the best water sources. It makes sense to try and camp at the main water sources where you will be filling for 2-3 days to save carrying extra weight.

• We all had 3-inch tyres, and I would not want to ride the route on anything less. Even with these, as mentioned above, we rode very low pressures at times to cope with the sand and the difference this makes cannot be overstated. Just riding a wide tyre is not enough. Even with these the sandiest roads were still really hard work. Notably Hana and I both use 40mm (ext) rims while Felix was using 35mm (ext), and although we all had 3-inch tyres, Felix struggled more in the worst sand. Other factors that make sand riding easier are an evenly balanced bike (if it’s extra heavy in back or front it will be harder) and shifting your weight forward on the saddle, while climbing, and back on the descents. We also actively adjusted our loads when we were carrying extra water; i.e. moving luggage from front to back or vice versa to keep bikes balanced.

• Gearing: All of us have very easy climbing gears on the bikes and we considered this an essential for still being able to pedal most of the hardest riding/climbing on the route. Sandy roads, 2-3 days water and food/fuel weight make the riding very demanding at times. Hana and I were riding 12 speed 1x, with a 10-50 cassette and 28t chainring. Felix rode 2x with 11-40 cassette and 22t smallest chainring.

• Camping: Because the afternoon winds are so strong and continuous, making the effort to get the best wind shelter possible is important, so you get better rest when you stop riding. Where we could we used Taneli’s best recommended sites, but sometimes we also made our own decisions. A couple of times we regretted not trying harder to find the best shelter we could, because sometimes the wind strengthens unexpectedly or changes direction.

• Overall, we tried to make the best decisions we could each day based on the information we had: water sources, wind shelter, energy levels and achieving milestones were all factored into our day-by-day plan. In general our spirit was ‘cautiously relaxed’ about the whole ride and looking back on it we were all quite unstressed considering our remote location, distance between water and vulnerability to a serious mechanical or bad weather. Being strongly self reliant and also in a team of three helped to make it a more relaxed experience. For comms/rescue we carried an InReach, which Hana and I have used for the past three and a half years on the road.

Thanks to Taneli Roininen for writing up this amazing route for Bikepacking.com and his brave solo exploration in the region.

Download the text for this post.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful?

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs. Every small donation helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Otso Cycles, Big Agnes, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow.

It is never boring . Just leaves me breathless, that you find such excruciating riding to be so exciting !! After the tragedy of our NE W ZEALAND volcanos, when so many people were killed (or burnt) I’d be inclined to give all volcanos a very wide berth. Looking forward to you reaching the green green grass of ARGENTINA ! Shouldn’t Hannah be wearing a WIDE BRIMMED HAT ? I admire your enthusiasm & energy. May it last until the end. Googled one of your previous blogs on death road, & decided I’d rather be on a bike than in a car ! Travel safely. Keep well. Keep up your wonderfully inspiring blogs ! An appreciative fan !

Fantastic trip, very remote and committing, well done!

Thanks Richard!

The two of you are mentors, that in my next life, I want to be exactly like you. Your drive to reach your 4 year goal must be leading most of the noteworthy explorers of the past; Lewis & Clark would be proud of your skill set and ability to tackle the kinds of problems that come up most every day. Good luck with the rest of the trip.

That is simply some superb riding and photography. Well done!