on the shoulders of giants

We’re a long way south since our last report was filed from the dusty Bolivian desert town of Uyuni on the edge of the salars. December 23rd, 2019 finds us in the Argentinian town of Fiambalá down at an oxygen rich and balmy elevation of 14oo metres. It’s a refreshing change from the stunningly beautiful, but harsh, high Atacama desert which has been the theme of our journey for the past nearly 1500km of riding.

We’ve covered this section of the journey in two major legs: from Uyuni to San Pedro de Atacama via the well known ‘Lagunas Route’ and the second leg via the much less explored Ruta de los Seis Miles, Norte. This long post covers the first leg, which also included an ascent of 6022m Vulcan Uturuncu along the way and in the company of fellow bikepacker Felix Blaß from Germany.

We had a good week in Uyuni, resting at the Casa Pingüi (casa de ciclistas) with our Colombian friends and several other cyclists from all over Latin America and Europe who passed through during our time. Uyuni would be the last big town we’d see for the 700-odd kilometres of remote riding to San Pedro in Chile, although we knew we would pass some small villages en route allowing resupply of some basics. Nevertheless, we left Uyuni with about 8 days food, reliant on the villages to buy a further 4 days worth as we travelled.

A farewell breakfast for the Colombian Monteadentro crew of five, who we rode with briefly near Sajama and on the Ruta de las Vicuñas. These guys are the vanguard of Colombian bikepacking, on a long trip from Cusco, Peru to Ushuaia by some of the most adventurous routes.

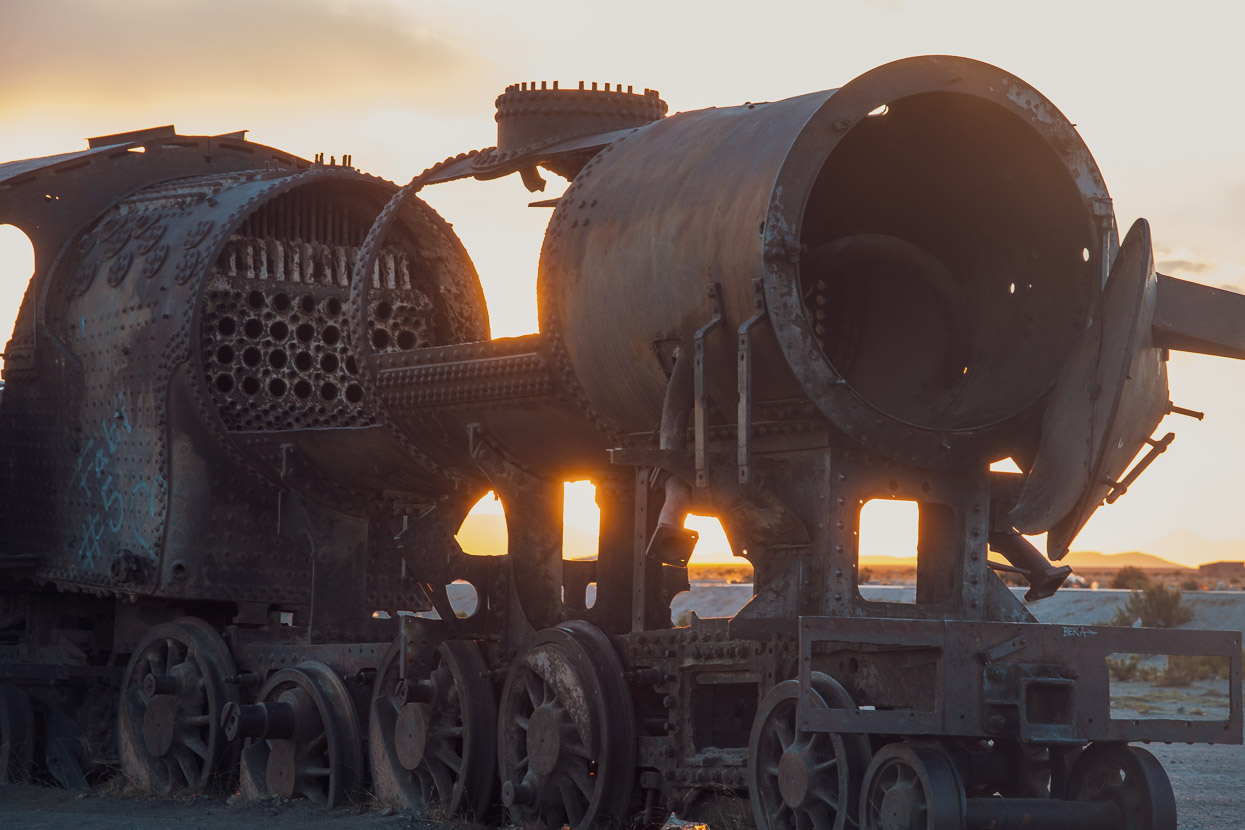

No visit to Uyuni would be complete without a visit to the Cementerio de los Trenes. It’s possibly a steam engine aficionado’s worst nightmare, but this sprawling area of rusting rail iron is a popular tourist attraction. From the late 19th century Bolivia administered a capable railway system mostly dedicated to transporting mining ore (gold, silver and other minerals) to the coast at Antofagasta. When Bolivia’s mining industry collapsed during the 1940s much of the network was abandoned, including a former carriage factory in Uyuni. Left behind in Uyuni were over 100 steam engines, box cars, tankers and flat carriages as well as various bogies and sections of track. The site has suffered from salvagers and thieves over the years, but what remains is still a solemn and spectacular testament to the glory of steam powered rail engineering.

For the first day out of Uyuni we followed dirt tracks and sometimes road alongside silent railway tracks to Rio Grande, where we slept in a basic hospedaje. The route follows the southern edge of the Salar de Uyuni before turning more directly southwards towards the village of San Juan, which we reached the next day for lunch. There’s no restaurant here, but you can buy supplies from the 2-3 well stocked tiendas. This town’s on the gringo tour trail, hence the good stores.

Other remnants of Bolivia’s former steam rail stand along the route – like a living museum.

The second night out of Uyuni was spent in a ruined railway station at the abandoned village of Chiguana. This section of the railway is actually still used (with diesel locomotives) to transport salt and lithium, which is extracted from the salars. Before moving in for the night we sought permission from a nearby military base. The soldiers are stationed in this remote valley, surrounded by volcanoes, in collection of squat, dome-roofed huts that looked as if they were from Tatooine.

Since entering this region of Bolivia (and Chile) we’ve found the iOverlander app very useful for water sources, camp sites and general POIs. And even more usefully it’s possible to export the iOverlander data for each country into OsmAnd (our preferred open source mapping app) for very quick reference.

From Chiguana we crossed a small salar and then began the first pass of the Lagunas Route which climbs up to a bit over 4000m and takes you to the higher puna which most of the route follows until it drops to San Pedro de Atacama in Chile. The Lagunas Route is notorious among cyclists for its extremely sandy, washboard roads which are churned into a mess by 4WD tours of the puna, which, rather than all stick to one route across the volcanic sands and ash-fields of the desert, often diverge to mess up a kilometre-wide swathe of land with tracks all over the place. Sad to see, especially considering a big chunk of the region is a national park.

A brewing thunderstorm gave us a sense of urgency to make the shelter of Los Flamencos. This (relatively) expensive hotel sits on the shore of Laguna Hedionda which is one of the best places on the route to view pink flamingos – by the thousands. Generously, the hotel has a basic cyclists dorm room for a reasonable price. We could not resist splashing out on their three course dinner though and had a treat that evening in the hotel dining room with a few other tourists. The good food was such a novelty for us that we really paced ourselves – savouring every bite and flavour, while the 4WD tourists at the table adjacent sat down to their meals after us and finished well before, hardly seeming to even appreciate it.

We got up extra early the following morning and walked just 100m down to the lake shore where we could watch the flamingos go about their morning feeding and preening. Remarkably not one single other tourist even came to the lake edge so we had the whole scene to ourselves for over an hour as we quietly observed and photographed the birds. The calm of the morning was alive with the sound of thousands of birds softly calling and pacing about the cold water.

It probably sounds like hyperbole, but this peaceful hour of bird watching (I’m sure I’ll be a twitcher when I’m too old to ride a bike) was one of the single best moments of our journey, due to the location and the scale and uniqueness of the scene before us.

We rode right to the famous Arbol de Piedra (Tree of Rock) that day passing through a challenging and surreal landscape shaped by millions of years of volcanic activity. Red, orange and yellow hued slopes swept uphill towards the mountain’s cones and craters. We passed ignimbrite outcrops, watchful vicuñas and battled the sometimes challenging surface of the road.

We stopped at a distinctive outcrop of layered rock late in the afternoon (good sheltered camping – marked on iOverlander as the site before Arbol de Piedra) and were surprised to see viscachas just hanging out on the rocks. Normally these elusive ‘rock rabbits’ flee as soon as they catch sight of you but these ones were incredibly tame – habituated to tourists who probably feed them, but it gave us a good opportunity for photos.

As the afternoon dragged into evening the wind began to blow colder and more strongly as thunderstorms capped nearby peaks, but we were spared the driving hail that usually accompanies these. The road got worse though and slowed us down a lot. Overall we rode pretty much 100% of the Lagunas Route, just having to push sideways sometimes to switch to a different – hopefully firmer – set of vehicle tracks, and we were very grateful to be doing it on 3-inch tyres and being able to run extremely low pressures thanks to being tubeless. I’d hate to do it on anything less, or with a heavy load. Overall my summary of the Lagunas Route is ‘Incredible scenery & wildlife; terrible bike ride.’ This may sound controversial to the legion cycle tourists who have trudged their way over the route, but really much of the actual riding is pretty bad and not becoming of a ‘classic’ bike ride. Were the road not so destroyed by 4WDs it would be a better ride, but as it is, it’s just something you have to put up with in return for some unforgettable scenery.

We made the arbol just as the sunset began to kick in. The Tree of Rock sits on the edge of a veritable forest of volcanic tuff outcrops and we found shelter for the night behind some nice formations. We thought we were alone there for the night, the tour groups long gone, but in the morning a lone Japanese cyclist appeared, having camped for the night elsewhere in the rock forest.

We couldn’t believe our luck in the early morning when an Andean fox ran by in the distance, and then reappeared sometime later sunning itself in a nook in the rocks. Another animal used to tourists, it let us get really close for a few photos.

With different angles and light, the arbol has many faces.

Kazuhiko was bravely taking on the Lagunas Route with a very heavily loaded bike and 1.5 inch tyres. Despite the riding being a complete mission for him and very slow, he seemed to be having a great time. How could you not with this scenery?

Our next stop was the famous Laguna Colorada, which is renowned for its red colouration due to algae in the water. The algae is, incidentally, the same stuff that the flamingos feed on and causes their pink colouration. The colour comes from a natural pink dye called canthaxanthin. The lake is a very special place, surrounded by volcanoes and home to many thousands of birds. Parts of it are also solid salt.

We’d only done a very short distance that day, so ate lunch, showered and rested for a while at one of the basic refugios on the NW shore, before riding up to the mirador at the northern end of the lake to camp for the night and take photos in the evening light.

Next morning we headed around the western shore, dropping down to a good single and double track that led right around to the peninsula mirador at the southern end of the lake. The lake’s colouration is best a little later in the morning once the sun is higher, around 10am, so we caught this at a good time, as well as many flamingos close to the shore as we rode the lake edge.

Our plan that day was to get close to the village of Quetena Chico, which would be our basecamp for an ascent of Uturuncu, but we had to cross another pass to get over to it. Before we could leave the Laguna Colorada basin we got slammed by a hailstorm, but at least the feisty weather gave us a good tailwind on the long climb up to 4820m.

Just 11km from Quetena Chico we camped in a beautiful rock canyon, hidden from the road and perfectly sheltered.

In the morning we had a clear view across to our goal: Volcan Uturuncu, which was looking pretty white from recent thunderstorms. What makes this mountain special for cyclists is not just the fact that it’s over 6000m, but that an entirely rideable road climbs to a saddle at nearly 5800m on the mountain’s upper slopes, making it one of the highest roads in the world. We hoped that the day would be warm and clear enough to melt some of the snow off before our ascent.

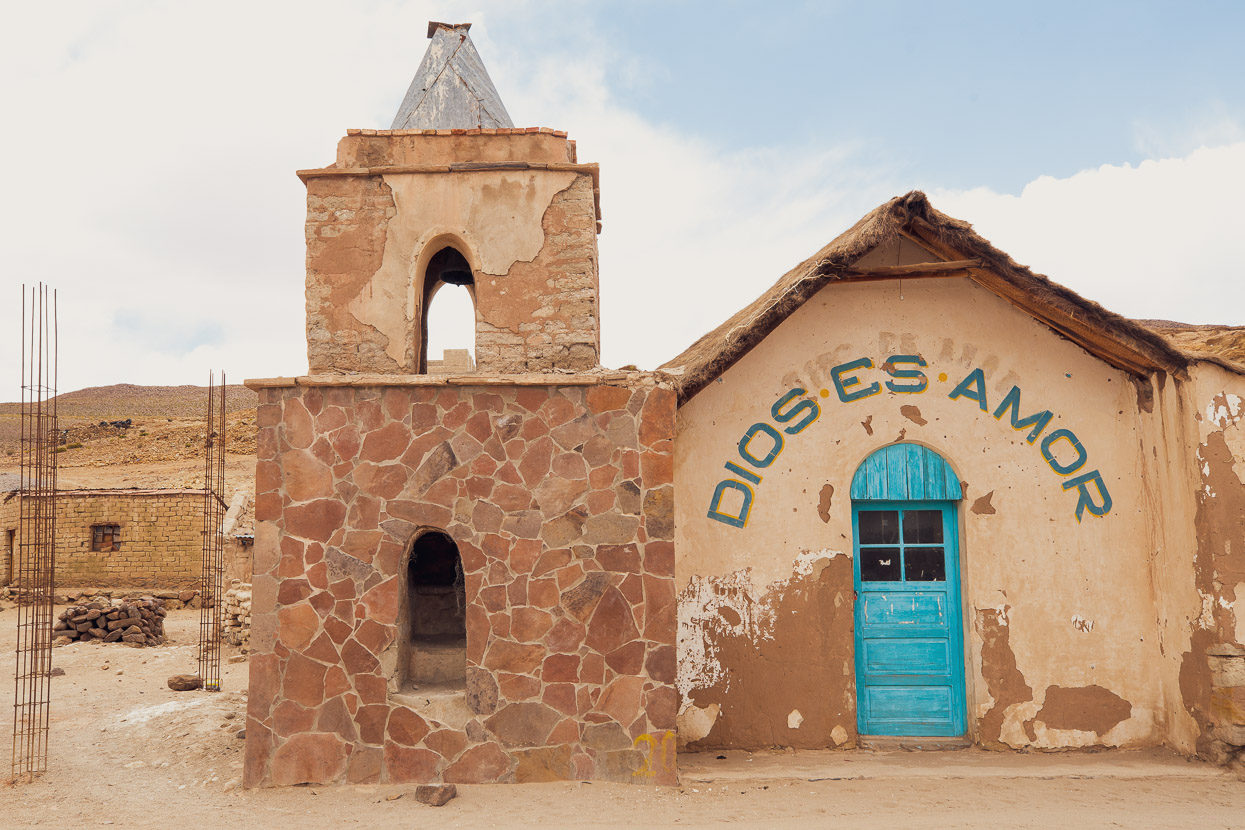

Quetena Chico doesn’t look much, with its low buildings and small military base, but it was a friendly little place with well stocked tiendas, a small restaurant and a basic, cheap hospedaje. The mountain is popular for guided ascents and a smattering of cyclists ride the mountain each season, so the locals are used to tourists. While we felt like we were in the middle of nowhere, there was also a large group of vehicle-supported Korean cyclists doing day rides in the area.

We spent the rest of the day organising ourselves and removing the racks from the bikes for an early start from the village. In case of a severe afternoon thunderstorm thwarting our plans, we decided to leave town at 2am, in hope of an early summit and return. Total elevation gain for the day would be a bit over 2000m on a sandy and rocky road, so we didn’t want to take any chances

We also had a rendezvous to make, with our friend Felix who was camped at 4800m on the mountain’s slopes. Felix intended to join us for the upcoming Ruta de los Seis Miles but had been based in San Pedro de Atacama in past weeks, losing both fitness and acclimatisation. So for a ‘get fit’ trip he rode, via a very remote route, solo, to join us on the mountain and then accompany us to San Pedro.

At 4.30 am in the morning, in conditions a few degrees below freezing we met Felix at his camp and enjoyed a cup of coca tea while he packed the rest of his kit away. We’d taken 2.5 hours to cover the first 800-odd metres of climbing and had been feeling cold much of the way up.

By the time we all hit the road together the sun was up and the day warming. We rode steadily uphill, and once above about 5200m, started to find it pretty hard going on the rough and steep road. But in the end we rode it all except for about 20m of washed out road.

It was a stunning place to be on a bike as the sun slowly brought the landscape to life.

We parked the bikes by a boulder on the saddle at about 5760m, put on some extra clothes for the cold wind, and then walked the remaining climb to the top. Considering our elevation we all felt pretty good, just hypoxic enough to be a bit spaced out and in my case, a slight headache.

Having a 360 degree view of high altitude puna around us was amazing, with many lakes, salars and other mountains visible.

It had taken us 9.5 hours total to reach the summit from Quetena Chico, including about an hour at Felix’s camp (we surprised him by being early). By 5pm we were back in the village, after a total elapsed time of 15 hours since leaving (including another 45 minutes at Felix’s camp on the way back down).

A lazy morning followed the next day and we left town in the early afternoon, riding just over 20km to a stunning campsite in a small side canyon of volcanic tuff. We had good wind shelter and an abundance of boulders to play on until nearly dark.

Just over the road was an oasis of green, brought to life by one of the few streams that run year round.

Rather than backtrack to rejoin the Lagunas Route we were following a route that would reconnect us at Salar de Chalviri, near the Termas de Polques. After a steep climb over a pass and then easier riding (albeit with a stiff headwind) past Lagunas Hedionda and Kollpa we reached the termas and hospedaje (there are a couple there) where we shared a dorm room with French cyclist Jean Pierre. The hospedaje had basic meals available and the termas were perfect along with a beer from the tienda/restaurant next door.

Just two short days separated us from the low elevation of San Pedro de Atacama, and after another pass and a section of very sandy and corrugated road we reached Lagunas Blanca and Verde. We could have kept going that day but we hoped for some good light for photography at the lagunas, which both sit in a spectacular position below the volcanoes of Llicancabur and Juriques. These beautiful peaks sit right on the border between Bolivia and Chile.

A cold, gale force wind blew all afternoon so we sought refuge inside the walls of an ancient, roofless casita where we camped under the stars.

Like most lakes in the region, Verde and Blanco (pictured) are saline and it’s common to see salt crusted up along the edges like ice during a freezing morning.

A sandy but straightforward ride around the lake and up a gentle climb led us to the Bolivian migracion building the next morning, where we stamped out of Bolivia (a week late) for the last time. The road onwards into Chile was wide and paved as we climbed further up to the Chilean migracion, and then a long and fast 2000m descent from the puna to the heat and aridity of San Pedro de Atacama. San Pedro would be our base for the next week as we prepared for the Ruta de los Seis Miles Norte, which I’ll cover in the next post.

For now, thanks to all for reading the blog through 2019, for your donations, messages and encouragement. It’s always fantastic to hear from followers. Wishing you all the best Christmas and New Year.

Hana & Mark.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful?

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs. Every small donation helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Otso Cycles, Big Agnes, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow.

Love the flamingo photos. I bet riding in that sandy stuff got a big old after a while.