‘the apolo mission’

In the north west of Bolivia, sandwiched closely between the Peruvian border and the Andes’ steep eastern descent to the Amazon, lies the Cordillera Apolobamba. This range of glaciated 5000–6000m peaks is well off the radar for most travellers to Bolivia, being in a remote part of the country far from any population centres or paved highways. But during our final couple of days in Peru, as we paralleled the border for a time, we’d had a glimpse of this range’s icy peaks emerging from behind the golden ridges of grassy puna and became tempted to explore.

While our curiosity was already piqued, it was a Facebook conversation with Kiwi friend Yvonne Pfluger that really convinced us to check the region out. Yvonne and her partner Tim did some mountaineering in the range in 2015, loved the region, and having seen that we were in that part of the world, suggested to us that it might be possible to bike right through the southern part of the cordillera, on a mixture of dirt roads and hiking trails.

We did a bit more research and discovered that the cordillera was once popular for the Apolobamba Trek, which traverses the southern part of the range from Pelechuco to Curva. But increased mining in the region (which is actually a protected conservation area) has led to ‘improvement’ of some of the trail into dirt roads. This is good news for bikepackers, but bad news for hikers and also the local tourist infrastructure which once relied on hiking parties for a bit of extra cash. With a large portion of the original trekking route now bulldozed, the trail has lost much of its hiking magic and these impressive mountains have become very much a backwater.

After much searching for GPX tracks online, perusing the Google satellite maps and OSM and reading hikers’ blogs we figured out that a good portion of the original trail remained south of Paso Quellhuacota where it descends to the Rio Akamani and joins the Akamani Trail, which in turn leads to sections of dirt road and pre-Columbian trail which can be followed out to Charazani. With this info we mapped out a rough plan in Ride With GPS. Anticipating a fair bit of hike-a-bike, we lightened the bikes by leaving some of our kit in the start/finish town of Charazani and hit the road.

At just under 3200m, the air was rich in Charazani after our extended time on the high puna following the Tres Cordilleras route and then our alternate out to Lake Titicaca and into Bolivia. It was also the biggest town we’d been in for a while. We spent a night there in the friendly family-run Residencial Inca Wasi, and they also looked after our extra gear while we rode the loop. The population in Charazani might be relatively large, but the choice on shop shelves wasn’t. Decent trail food is proving hard to find in Bolivia.

The town is sited on the eastern side of the Andes in one of the major inter-Andean valleys that flows right down to the Amazon. Its location makes it an important trading post and nexus between the mountains and jungle. These valleys are also known for their Kallawaya people, in particular their itinerant healers. The Kallawaya are direct descendants of the Tiwanaku culture and closely linked to the Mollo.

First on the menu was a 1300m climb out of Charazani via the Rio Chari. This long and sometimes rough climb followed a scenic valley and brought us back to the puna.

From being on the cusp of the cloud forest we were soon back to windswept grasslands and herds of vicuña.

Moody afternoon weather raged in the mountains, continuing the bad weather trend of the past couple of days, which had brought snow to quite low levels.

We pedalled north along the puna, just west of the Cordillera Apolobamba, actually following the original Tres Cordilleras route towards Suches Lake. This section is seldom ridden now due to the closing of the Suches border crossing (see previous post).

At Ulla Ulla there is a campamento ranger station (the building in the photo) and a park accommodation building which travellers are welcome to use to overnight in for a small fee. There’s electricity, a small kitchen and even a phone signal. The region is all part of the Area Natural de Manejo Integrado Apolobamba protected area — a conservation area basically, although the definition of that here is quite different to that of New Zealand or the United States. Mining (state/private and illegal), farming and animal grazing are too important to the economy and culture for those activities to be banned, so sadly they go on largely unregulated within the park boundaries.

Coincidentally, we met park director Julio Callancho Canasa with some of the other rangers at the campamento and they immediately invited us to stay in their accomodation building. Julio pointed out to us that it’s not actually permitted (for anybody) to visit the park without written permission from the SERNAP headquarters in La Paz, but that seeing as he was the boss, he’d let us continue as long as we checked in at the campamento stations at Pelechuco and Lagunillas. Julio also promised to make some phone calls to assure our passage.

It had been late by the time the rangers set us up with accommodation, but in the morning the whole crew were back to have a go on our bikes and take some photos with us. Gringo ciclistas are rarely seen in these parts. That’s Julio on the far right.

Despite us being in the park unofficially, the rangers were ultra enthusiastic to see us there and excited for our mission to ride/hike through to Curva and Charazani. Lots of gestures indicating carrying bikes on shoulders were made.

We were wished well and then carried on into a frigid morning, much of the landscape dusted with a thin layer of snow from the previous evening’s storm. The rough dirt roads took us further north, and we then turned east, passing through a mine and a military checkpoint at the village of Antaquilla. The road led deeper into the mountains, climbing gently towards the Andean divide.

The first high pass of the loop came at 4845m. We lingered there for a couple of hours, waiting for the thick afternoon mist to break before picking a spot to set up camp just a little further down the road.

It was worth waiting around for. The mist soon cleared completely to leave a cloud speckled sky brilliantly lit by the rising moon. A campsite to remember.

With the light of dawn we explored our surroundings a bit more, in no rush to plunge downhill into the still shady valley. A long descent to Pelechuco awaited.

We could easily have made Pelechuco the previous day, but we wanted the high camp and time to savour the highest parts of the mountains a much as possible. It meant earlier sun too — always nice after a sub-zero night.

No complaints about the scenery so far…

By mid morning we’d made it down to Pelechuco, at a balmy elevation of 3600m. This town’s colonial history is extensive, having been founded in 1560 and like Charazani the town has historically been a key trading point between the mountains and the jungle. With its crooked cobbled roads, stone buildings and peaceful ambience it’s a very pleasant spot, and we enjoyed the rest of the day chilling out and wandering around the village. There’s a few tiendas and we were able to stock up on a bit of food for the coming days.

The view down valley, towards the Amazon. We were right on the edge of the cloud forest zone.

But the following day it was uphill again for us, with a very steep 1000m climb making us glad of our afternoon off. Despite the rest we still found the climb quite tough, but the scattered Mollo ruins along the valley floors and the small herds of llama gave us a distraction from the effort.

As expected, our efforts were not in vain and the scenery became more and more impressive the higher we climbed.

We topped out Paso Katantika at 4707m, donned jackets and plunged down a rocky descent on the backside. The road was crusted with frozen snow in places on this shady side of the mountain. An afternoon storm was brewing, which comes with the territory, this close to the Amazon basin, so we got lower as quick as we could.

We caught some nice glimpses of the valley through the cloud before the mist, drizzle and hail closed right in. These conditions chased us right down to Hilo Hilo, where we planned to spend the night. We’d only covered 21km that day, but they’d been hard earned.

There’s one very basic hospedaje in the village and a couple of small one-dish restaurants. We had to wait quite a while for the owner to come and open us up a room. After dropping our bags on the two dusty single beds we noted the lack of a bathroom. When we asked where it was the woman pointed to a lonely corrugated iron longdrop on the outskirts of the village. Judging by the state of it most of its visitors were too drunk to point their bottoms at the small hole in the ground.

One of the biggest differences we’ve noted between Peru and Bolivia so far is the quality of the food available in small stores. Sadly it’s taken a step down even from Peru’s spartan options. Lunch is easy enough (usually bread rolls or crackers with cheese or tuna and mayo), but it’s very hard to find nutritious snacks. Even peanuts are a rarity, so we usually have to stock up on sugary rubbish that leaves us constantly hungry. Combined with the food I bought in Pelechuco, this was three days worth of snacks and lunch for myself.

Hilo Hilo had been fog shrouded, cold and damp when we arrived. Early in the evening we went hunting for dinner and found the one open restaurant. It was a small dirt floored affair, with an overworked indigenous woman at the cooking pots and her two children taking care of serving food to the three plastic tables in the room.

We’d not been there long when three drunk miners barged into the room and stumbled over to a spare table. They ordered beer and food and mumbled their way through a noisy conversation, sometimes shouting at each other. One was drunker than the other two, his head lolling on his shoulders while a long string of drool hung from the corner of his mouth. He kept turning silently, head wobbling, and staring at us, as if he could just make out through his drunken haze and double vision that two of the people in the room had paler skin than the rest.

The men tucked into their plates of rice and chicken, encouraging the extra drunk guy to do so with some slaps on the back. He could barely keep his face above the plate, ever-threatening to collapse into it, but somehow he shovelled in the food, chewing slowly and relentlessly like a cow. Halfway through our meals, Hana and I watched nervously, wondering if he would fall over and knock himself out, or lose the food he was so laboriously masticating. Sadly for us it was the latter. All of a sudden he half stood, lurched towards us, and then vomited violently in our direction. A vile acidic cascade splashed onto the ground at our feet, dotting our shoes with specks of vomit. The man fell to his knees, nearly crowning himself on our table and then tried to stand. His two friends leapt up and tried to carry him through the narrow door so he could void the rest of his stomach in the street.

The cook and her children looked on blankly, as if this was a gross, but not unusual, occurrence. The pile of vomit sat there for a few minutes, steaming away, as we gagged down the rest of our food. The oldest girl scooped up most of the vomit and threw it outside, where a happy stray probably tucked into it.

Despite our traumatising meal we slept well, exhausted from the days climb, and looking forward to more. The morning dawned spectacularly clear and calm and we were off early. Ahead lay another long climb to just over 5000m, where we planned to camp.

We turned our heads and stopped frequently that morning as we gradually gained height out of Hilo Hilo and the views opened up. We’d had no sense of the surroundings after our foggy descent the previous day.

It was a stunning ride; one of the best passes we’ve ridden since Cusco, with small clusters of old stone farmhouses in the lowest pampa and then nice alpine wetlands, craggy peaks and big views of the range as we gained height.

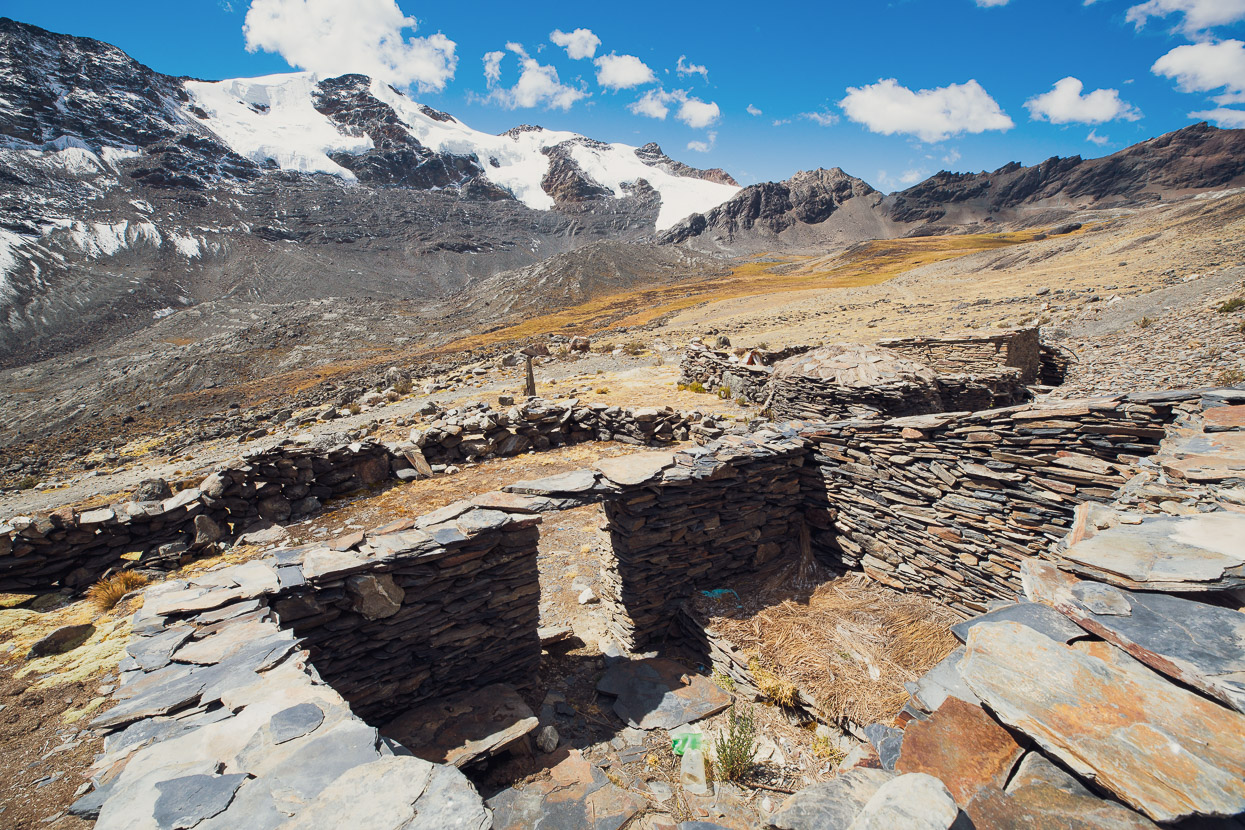

We lunched at an abandoned gold miners camp, hiding from the cold wind behind the carefully built stone walls.

The final haul up to Paso Sunchulli. Little engineering goes into these roads — they’re just crudely blasted into the mountainside and bulldozed.

Again, we wanted to camp high for some mountain views and light, so we pitched the tent right on the pass on a small shelf of scree. A brief snowstorm blew in shortly after we arrived, but we knew it wouldn’t last.

And then out of the blue, a SERNAP 4WD appeared, from the direction we were headed. It was the rangers we’d met in Ulla Ulla. They were glad to see us. Hands were shaken, questions asked. It turned out they’d actually been looking for us to make sure we were ok and had driven right in from Ulla Ulla. The SERNAP office in Pelechuco had been closed, so we had not signed in there, but it wasn’t clear if this is what prompted the search. I suspect the team were looking for an excuse to go for a drive in their stunning park and try to catch up with the gringos. Anyway, lots of selfies and group photos were taken with us, our GPS location recorded and one ranger drew us a little map to help us navigate the next section. This was very useful, as we were partly relying on guess work for one critical section.

Sure enough the cloud mostly cleared, the wind dropped completely and we had a calm and comfortable night at 5040m. Not bad for a three-season tent and -7c sleeping bags. The Big Agnes Copper Spur HVUL2 is proving to be a very versatile shelter.

In the morning Cololo (5915m) dominated the skyline to the north. The peaks in the photos below are Canisaya (5706m) and Cuchillo (5655m).

Our route onwards followed the sunlit road.

Another perfect morning with warm sunshine and little wind. We dropped into the valley, passed a big camp that supports a gold mining operation (a big local employer) and began the next climb. Apparently this valley has been mined for gold since Inca times, so it’s nothing new — just a lot bigger.

On this day the cloud rolled in earlier and as we made our way to the big descent to the Rio Akamani visibility shrank. After a while we turned off the soon-to-terminate road and picked our way cross country towards Paso Quellhuacota which marks the descent down the notorious ‘Mil Curvas’ (thousand corners) descent.

Along the way we found the perfect picnic table for lunch.

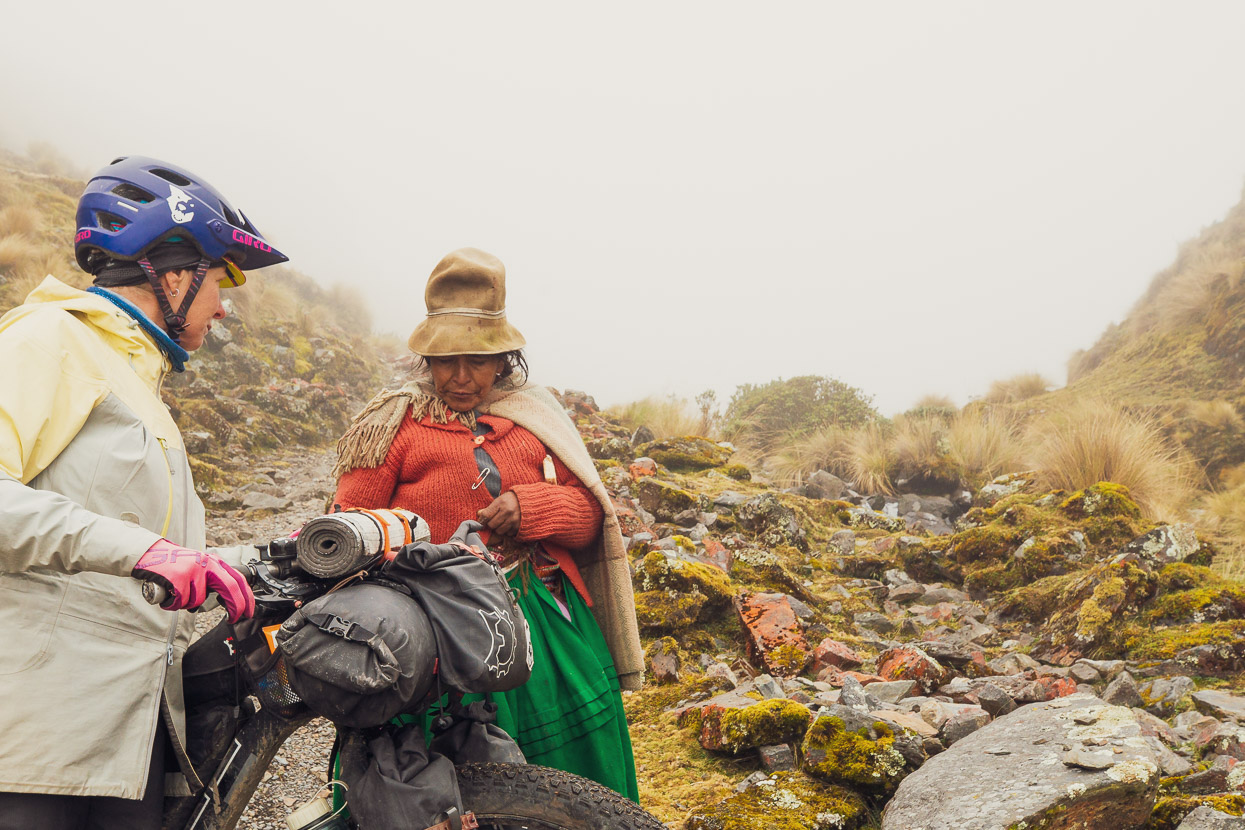

For us Quellhuacota was the beginning of a downhill hike-a-bike to reach the Akamani trail in the valley below. This route is part of the original Apolobamba Trek. At first we tried to follow the Mil Curvas option (there are two routes), but it was choked with quite a lot of snow. It’s also very steep as it descends a narrow gut between two cliffs. I ran down this section a way to check it out but in the end we deemed it a bit sketchy in those conditions. The rangers had told us that the alternative was a bit less steep, but less direct, so we decided to go for that in the end. In the photo Hana is contemplating the steepest bit, which went on for about 30 minutes before it widened and even became rideable in parts. By this stage light rain had kicked in and visibility was quite bad.

Still heading for the rideable bit…

In the end we made it to the valley floor safely and then made our way cross country to join the Akamani Trail which is marked and labelled on OSM. Thus commences about 700m vertical of hike-a-bike to reach the final pass of the route: Paso de Tambillo. We did about 45 minutes worth in steady drizzle and then stopped at the ruin of an Inca house (the location is locally known as Incacancha), the stonewall of which made a perfect wind break. The drizzle continued all night and into the following morning, with a couple of very brief pauses.

Roughly 600 vertical metres of hike-a-bike remained, which we stubbornly ground down with a mixture of pushing and carrying. We spend the entire morning in a mist bubble and longed for some views of our new surroundings.

Finally we topped the pass, ate a quick snack and then were very pleased to discover that the ensuing descent was 95% rideable, and much of it a lot of fun. Like much of the remaining Apolobamba Trek, the route follows a pre-Columbian road that would have been used for trade, by foot and llama, so it’s pretty well formed into the hillside in a lot of places, making for some very nice riding.

We made good time, passing an extremely medieval looking farming hamlet, before dropping further then making a short climb up to Cañisaya, an ancient stone bridge marking the entrance to the village. We had a late lunch there, much to the interest of a bunch of very curious school kids who see few gringos in the region these days.

Our route then passed through Lagunillas and Curva via dirt roads before beginning a big descent into a tributary of the Rio Charazani. We’d taken the cue for this section from a GPX we’d found for a route taken by a French hiker, so we were a bit unsure about what we might find, but in the end it was a pleasant surprise. Just before the road deadended part way into the valley another good quality pre-Columbian trail turned off and descended rapidly though extensive stone terracing. The trail is incredibly well preserved, with retaining walls still in place much of the way. The trail dropped us to a sturdy concrete bridge, which felt incongruous in the middle of a remote valley only accessible by foot or horse.

A solid hike-a-bike commenced as we left the narrow valley, still following ancient switchbacked trail much of the time. After about 45 minutes the angle mellowed and it became rideable as we sidled and undulated gently around the mountainside towards Niñocorin.

This section is a very memorable bit of riding, with a nice trail that winds its way through pre-Inca (probably Mollo) ruins. They were distinctive for the many remains of stone roundhouses, stone walls and terracing. It’s amazing this site is not better known and I have not even been able to verify its name.

We didn’t stop in Niñocorin, but it was another very old, traditional looking village. Darkness was looming, so we pressed on to the final short climb and fast descent down into the valley below Charazani and a final haul up into the village on very tired legs.

For anyone interested in following this route, or bikepacking in the region, for the time being, permission is required from the SERNAP office in La Paz, Bolivia. You need to go in person.

Calle Francisco Beddregal No 2904 Zona Sopocachi

Phone: 2426265 2426268

http://www.sernap.gob.bo

inf@

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful?

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs. Every small donation helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Otso Cycles, Big Agnes, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow.

Hi Mark, thanks loads for being so generous with your information. I’ll be heading on a similar path next year and will be following one or two of your routes. Please accept a few beers on me. Cheers. Oh yeah, your photography is stunning!

Dermot

Thanks so much Dermot, that’s so kind of you! Glad you find the content useful and the photography enjoyable! If you have any questions re route or anything else, fire away.

cheers Mark + Hana

Wow, that is some insane terrain Mark. Well done!

Thanks Matthew – it was definitely worth the effort!