ruta de las tres cordilleras

On the 1st July we resumed our journey southbound towards Bolivia following the Ruta de las Tres Cordilleras.

After our Ausangate – Rainbow Mountain – Valle Rojo linkup we’d spent two nights back in Cusco to recover and pick up more supplies. We then bussed back to Pitumarca (where we had left the bikes) and taxied with the bikes up to the village of Chillca at 4300m. From there a ride of just 3km linked us back to the Tres Cordilleras route, where it continues south from the Ausangate region. It felt good to be back on the bikes, rested, and after suffering through the Ausangate circuit, properly acclimatised too.

The Tres Cordilleras route does not muck around, and consequently the first item on the menu was a climb to a pass at 5040m. Looking back we had a nice final view of Chillca and the surrounding landscape.

We were alone on the road as it snaked its way slowly up through a peaceful valley.

The other side of the pass dropped briefly and entered a high altitude basin, ringed with rocky peaks and the snowy domes of the peaks of the Cordillera Vilcanota.

We made camp beside a small stream as the sun dipped towards the horizon.

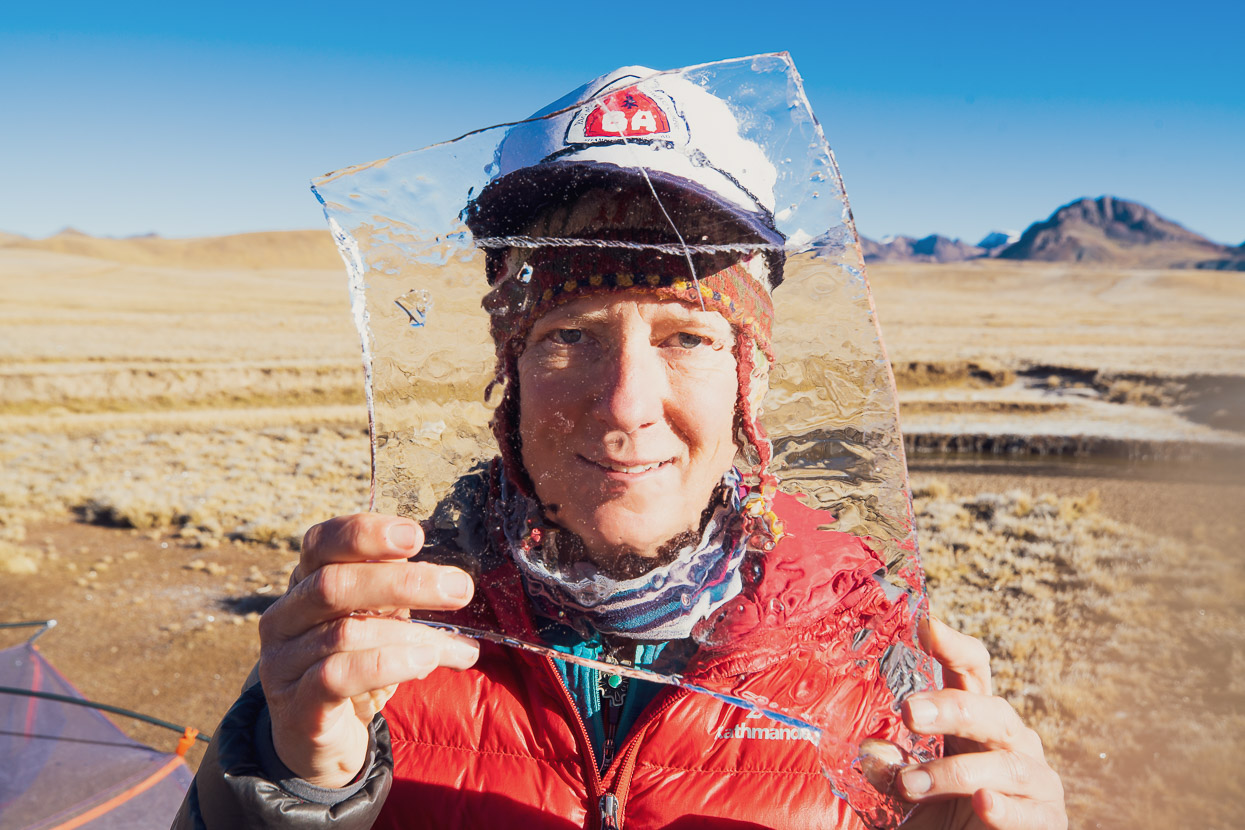

As the warmth of the sun departed the basin the temperature dropped steadily; down to -5c within 30 minutes and by the time we’d cooked dinner it was already -10c. We slept in all our clothes (we’re using -7c Big Agnes Hitchens sleeping bags with our three season Copper Spur bikepacking tent) and woke to a chilly -15c. Some impressive frost crystals had formed on the tent and bikes during the calm and freezing night at 4800m.

We’d neglected to put some of our water in our sleeping bags so it was all frozen solid, but with some bashing we managed to crack the ice on the stream.

The first rays of the rising sun were a welcome relief to the nip of the cold.

We continued through the sparsely populated region, seeing more vicuñas than people and the odd herd of alpacas, grazing on the sunny slopes.

The mountains of this region are well off the gringo trail and seldom seen. Few outsiders visit, except the occasional bikepacker or climbing party.

For much of the morning the Ritipampa de Quellcaya filled our view ahead. This giant icecap was once the largest in the tropics (now second to Volcan Coropuna near Arequipa). Sadly, its days are numbered. Our warming climate is blitzing its ice mass and it’s predicted to be gone by 2050. With its loss, the livelihoods of thousands of hardy farming folk who live scattered over the puna will be under threat as their water supply dwindles away.

We had an early lunch in the village of Phinaya, sitting in the sun outside the tienda with our plates of potato, egg and salad before beginning another climb to over 5000m on the Abra Jahuaycate (5070m). This one was a bit steeper than the previous day and had us breathing pretty hard.

But as always a reward came in the form of stunning alpine views and a long and winding descent into the Valle Corani.

The landscapes and geology of the Tres Cordilleras route continued to morph the following morning as we dropped into a canyon of sandstone cliffs, towers and boulders. This landscape continued almost the entire day through to the town of Macusani.

Macusani, just under 4400m, is the biggest town on the Tres Cordilleras until it reaches Sorata, Bolivia. It’s a bustling service town, noisy with truck and bus engines and tooting horns as smoke-belching vehicles pass through town on a highway that eventually plunges over 3500m down into the valleys of the Amazonian hinterland. We took a rest day there, hoping to eat well before more long days riding through the mountains, but despite an abundance of restaurants their offerings were all disappointing. Perhaps we’d been too spoiled in Cusco and needed to relearn to abandon all hope of good food, but we ended up eating the ubiquitous pollo a la brasa two night in a row. At least the chips were hot and it came with salad.

Interestingly we were stared at a lot, as if very few gringos pass this way, and indeed throughout the northern section of the Tres Cordilleras we often felt like we were the only gringos to have traversed these remote roads and towns, such were the curious and friendly responses we had from most locals.

Typically I spend a rest day (apart from cramming calories) editing photos, blogging and usually wandering around town to take photos, but that day I was uncharacteristically exhausted. The morning was clouded with a thick brain fog and I slept for two hours in the afternoon – those 5000m passes must have been more taxing than we thought. But in the late afternoon I finally dragged myself out and made some photographs. The light in this region has to be seen to be believed; the high altitude air is so clear and the golden hour light so nice that photos take on a very crisp and clear quality.

Among the buildings of town and with your view hemmed by the golden ridges of the puna it’s easy to forget where you really are, but some impressive mountains tower over Macusani, notably the highest peak of the Cordillera Carabaya, Ch’ichi Qhapaq (5614m).

Easier riding on a cold and cloudy day took us through to the freezing cold highway town of Crucero. We took a hotel room there for the night, but the room was so arctic we sat in bed with down jackets and hats on. When we decided to brave the on-demand electric shower it had a melt down, filling the room with a combination of steam and smoke before pulsing orange as the element fried itself.

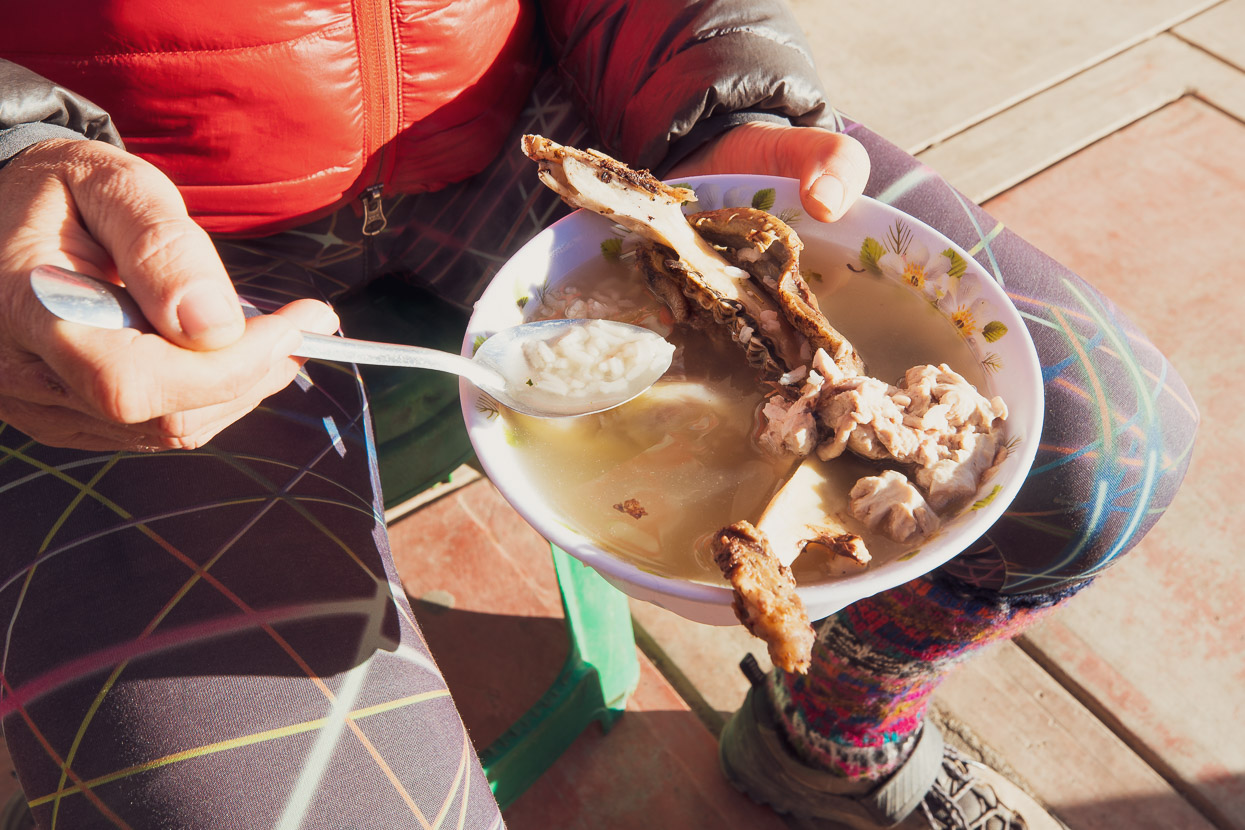

The following morning was my 48th birthday, so for a treat we decided to get breakfast in town instead of eating oats and instant coffee. There were a number of carts already set up around the plaza in the sub zero temperature. With blankets over their shoulders women stooped over mysterious pots of food, which they issued to customers in steaming dollops. We optimistically picked the tempting sounding caldo de alpaca, only to watch in horror as the woman plucked us a whole alpaca jawbone each from a pot and placed them into bowls of foul smelling meaty broth. The final item was a creamy coloured globular substance that I can only guess was a luckless animal’s brains.

We’re pretty open minded when it comes to food, and definitely not very fussy after two years cycling in Latin America, but the chunk of fatty alpaca cheek clinging to the bone was gross and yielded only a couple of mouthfuls of edible meat, and the animal had clearly not looked after its teeth. Even now when I recall the odour of the soup my stomach turns. We discretely threw the rest of the cheeks to the dogs, scooped out the last of the rice from the fatty, rotten smelling broth and handed the bowls back with a feigned smile. At least it only cost $2.

By this time a restaurant had opened its steel doors and we slipped inside, drinking coffee and eating stale bread at a plastic table, while a toothless octogenarian slurped soup noisily beside us.

A long steady climb carried us out of town past some peaceful lakes and over a pass on the east Andean divide.

It was a fascinating area, with heavily stratified geology and of course, few people.

In fact, far more llamas than people…

After a long descent, we rattled our way over a stony road into Carhuapata. This small village sits on the margin of the cloud forest zone and the brink of the great selva (jungle) that lies below the eastern side of the Andes. We picked up some snacks from a small tienda there and chatted with the woman from the store who said she had not seen a gringo for a long time. Then it was back towards the altiplano west of the divide, via a separate valley.

After climbing for a while we passed through the stone village of Carrizal. Remove the few tin roofs and the powerlines and this village could have been a scene from 200 years ago. The place was deserted except for a lone boy, sitting out of the wind on his battered bicycle with a big radio around his neck. Roni told us he liked to listen to music and the football.

A few of the women we saw in the two valleys still wear their traditional monteras (hats), which are quite different to the bowler or top hat style we see a lot more of. Even more uncommonly this woman was okay with being photographed after I gestured with my camera and asked politely un fotito de usted, por favor? Possibly she did not even speak much Spanish, but it did the trick. Shortly after, her husband came running over, softly shaking our hands and asking us why we were in the valley and whether we were bringing anything. It’s not an uncommon question in these remote parts of the world, where people seem unable to comprehend that we are just there to explore, learn and appreciate. They seem to imagine that we are missionaries, NGO volunteers or traders.

Further up the valley, we were just laying our bikes down on the grass at our campsite for the night, when this character came bounding down the hillside above us. Benedicto was on his way to his casa, tucked away in a distant quebrada (valley) after working with his alpacas for the day on the pampa above, but upon seeing a couple of strangers in his valley he went out of his way to come and say hi. Full of energy and good vibes Bendicto asked us all about the bikes and what we were doing, before blessing us and making his way home-bound along a faint hillside path in the fading light.

It was a really nice spot to be for the night, just a couple of metres from a babbling stream that coursed its way over small limestone bluffs (the spot is waypointed on the Tres Cordilleras GPX). We watched the dawn sky shift from colour to colour as we ate breakfast in the tent.

The next day the landscape continued to be ample distraction from the effort of riding a bike at well over 4000m.

We crossed back over to the west of the divide, sometimes just riding cross country over the bumpy puna before we linked with another dusty dirt road and crossed a pass back to the east again. As the afternoon dwindled we plunged downhill on a fast road until eventually a cold mist swallowed us and we sidled around a deep canyon towards Patambuco.

After a big day we were quite looking forward to a real bed. We soon located the duena (owner) of the only hostal in town, who also ran an extremely cluttered general store, which she gestured inside, suggesting we store our bikes there safely for the night. We tripped over shoe boxes, dusty six packs of Cusqueña and an alpaca’s head and feet that she was saving to make a soup the following morning, but managed to stash the bikes in the back of the mud brick walled shop.

Upstairs was a single dormitory, with eight aged and saggy beds arranged over a creaky wooden floor. The bedding didn’t look as if it had ever been changed, or the room cleaned (which we’re quite used to in rural Peru). We brushed rat poo and dust off the beds and spread out our sleeping bags, still grateful for some space and the warmth of the lower elevation.

Food options were lean: it was caldo de gallina or nothing. This Peruvian style chicken soup is a specialty of the country and is one of my favourites, usually served as a rich broth with a fleshy chunk of meat, a boiled egg, a potato and with spaghetti or rice also in the mix. Some toasted maize, a sprinkle of aji (chili), spring onion and a squeeze of lime brings out the best of the flavour. That evening I could not resist a second helping.

When we rose early the next day the dueña was sat outside in the morning sun. Her dismembered alpaca was on the boil and she was busy sorting through her chuños, which are small freeze dried potatoes. Using traditional processes dating back to Pre-Inca times, Peruvians of the high Andean regions continue to seasonally bulk freeze dry their potatoes, by baking them in the sun during the day and freezing them in the sub-zero nights. Part of the ritual involves trampling them to squeeze out the last of the water and remove the skins.

These potatoes are a staple of the campesino’s diet and treated in this way can be safely stored for up to decades.

The law of cycling in the Andes is that what goes down must again go up, and so we we were soon climbing again towards a 4400m pass, through more beautiful and rugged east Andean valleys.

We ended the day 1000m lower than the pass in the historic village of Cuyo Cuyo. The valleys surrounding this isolated place are covered in the most extensive pre-Inca terracing we’ve seen anywhere in South America; literally hundreds of kilometres worth. There are also hot pools, so it made the perfect place for a rest day.

A unique feature of the andenes (terraces) here, are the in-situ alcoves, which we gather were used as grain storage. Because temperatures regularly fall below freezing here during the peak of the winter, the chambers were probably used to store harvested grain and protect it. We spend the afternoon exploring the terraces (a two hour loop walk from town). Unexpectedly we also discovered that at some time (possibly post-Columbian) the convenient alcoves began to be used as burial chambers. Even the first couple that we arrived at low down on the terraces contained human remains and some showed signs of looting.

The original Tres Cordilleras ride was made by bikepacking route pioneers Cass Gilbert and Michael Dammer, who rode it from Sorata to Cusco (NW-bound). They descended into the Cuyo Cuyo valley down a narrow, stepped and switchbacked section of Inca trail (photo above), which by all accounts makes a pretty hideous ascent in the opposite direction. But fortunately there’s a still very scenic double-track option that climbs the true right of the valley onto the altiplano (thanks Rodada de Mel for the tip). It’s a 1200m climb, which took us a few hours, but the whole time we saw only one colectivo van and one old indigenous woman sorting her chuños in the sun.

But as we approached the mining town of Ananea the contrast to the surroundings of our long climb could not have been greater. Rich in gold, the ancient moraines surrounding the northern Cordillera Apolobamba have been utterly devastated by mining. Mountains of tailings dominate the landscape, and between them settling ponds, reservoirs and pits scar the land. Waterways have been contaminated and most likely more damage awaits.

While Ananea was busy enough, the highest permanent settlement in the world sits another 500 metres higher near the snowline on Nevado Ananea (5800m). El Rinconada (5100m) only exists because of Peru’s rampant mining industry.

For us Ananea was a place to stash the bikes for two days while we bussed out to the city of Puno on the edge of Lake Titicaca. We needed to collect the final paperwork for our overstay fine (we successfully applied for a fraccionamiento, which means we paid just 10% of the 4.20 sole daily fine when we left the country. The remainder is paid if we return within 5 years, otherwise it’s wiped). We also asked about a post-dated exit visa for Peru, so as to enable us to continue south on the original Tres Cordilleras route, but this was firmly declined. Given we’d already overstayed 6 months in Peru, we chose not to push immigration any further, and instead plotted out a still-dirt alternate that would deposit us neatly at the Tilali/Puerto Acosta border with Bolivia. It would be our final three days of riding in Peru.

I’ll cover the details of that in the next post. For now, thanks for reading!

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful?

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs. Every small donation helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Otso Cycles, Big Agnes, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow.

Fantastic photographic vistas of mountains & landscapes tho I do believe I’m ‘mountained out ! You will never forget. Your 48th Birthday ! You must constantly dream of acceptable food ? But hey there, you’re both survivors. Looking forward to reading about Bolivia. Love seeing & hearing about all the characters you meet on the journey; travel safely. With my heartfelt admiration !’

Thanks Mark for another visual buffet. Hopefully you’ll be posting that recipe for the alpaca soup soon 🙂

As always, I love to view your blog on my 32″ wrap around monitor!! You two make my day. I was curious as to how far ahead have you been planning your trip and what in general is your estimated arrive at the final goal? You two take care, your an inspiration to many….vic & joy

Awe inspiring . I’m sure the route in person is even grandeur.