“sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you”

To many people the title ‘Inca Trail’ means a popular multi-day trek from the Sacred Valley of the Inca through to Machu Picchu. But the trail doesn’t end there. There were in fact many Inca trails, or more correctly ‘roads’. At its zenith the Inca Empire stretched from southern Colombia right down to Chile — a huge amount of territory. But to control their empire, trade and move troops and royalty the Inca expanded on a earlier road network to create over 39,900 km of mostly hard surfaced tracks. They were the preserve of the elite and subjects of the empire were forbidden from using them. The Qhapaq Ñan constituted the most important of these roads, traversing the Andes for 6000 km.

According to American field archaeologist and Inca expert Gary Ziegler, the so called ‘Inca Trail’ actually extended well beyond: linking the Sacred Valley to Machu Picchu, the Llactapata ruins and right to the citadel of Vitcos (our destination for this instalment) and further northwest towards the Amazon, no doubt serving as a vital trade and transport link. Some sections of this road to the jungle are kept open by local communities and campesinos who utilise it themselves, while others have been lost to the forest or smothered by landslides. Even today it is still being explored and new ruins and Inca infrastructure discovered.

From Santa Teresa our dilemma had been to pick the most interesting (read adventurous) way to travel on to the site of Vitcos and beyond to Espiritu Pampa. There was a road through to the town of Huancacalle, at Vitcos (least desirable), or the option of backtracking for a day and then riding over a high pass to Yanama, where the road intersects a former Inca road that crosses the Choquecatarbo Pass. We knew little about the route, except that trekking groups sometimes cross it as an extension of the Choquequirao Trek, or as a trek to Espiritu Pampa. A friend of our hostel owner in Santa Teresa produced a third option: The Abra Mojon (Mojon Pass). He described a seldom-used but apparently beautiful route that crossed the western Cordillera Vilcabamba, close to some of its glaciated peaks, via a series of 4000m+ passes before descending to Huancacalle, a journey of around 60 km.

‘Ride to the village of Yanatile, and then keep going to a bridge, from there the track climbs. You’ll find it ok,’ he said.

Open Street and Google maps on our phones revealed little about his suggestion: we could see Yanatile, but there was no road shown to there from Santa Teresa and beyond; not even a track. The passes, lakes and many of the peaks were unnamed. Online, we discovered that Abra Mojon was indeed crossed by a rarely used Inca road, offered as a trek by some Cusco-based outfits and we discovered one GPX track of what we thought must be the route. Enough to go on.

What we didn’t realise at the time was that we’d actually be following the continuation of the Sacred Valley–Machu Picchu Inca Road, or quite what we were getting ourselves in for. See map at end of post.

Shortly after leaving Santa Teresa were were pedalling through lush surroundings of coffee and banana plants. There was indeed a road to Yanatile.

After climbing for 500 vertical metres alongside the Rio Sacsara we reached the one-street pueblito of Yanatile, which was the last village we’d see for three days. It’s actually big enough to have a small tienda, so we stopped to buy a couple of refrescos to have with lunch and chatted awhile with the owner, who was both surprised to see us and even more surprised we were continuing up the valley with bikes.

After Yanatile the road deteriorated rapidly, from double track, to an unmaintained road that was being overcome more and more each wet season by slips.

The road might have been falling apart, but we were loving the surroundings. We climbed another 1000 vertical metres, leaving the humid jungle-like surrounds behind and gaining cooler cloud forest. Steady light rain had set in by now.

The few locals who we’d spoken to on our way up the valley had all mentioned a place name at the end of the road. So we’d assumed there to be a small settlement there but we arrived to find nothing more than a bridge signalling the end of our ride up valley. From there a steep single track — the Inca road — climbed into a side valley. We saw a couple of campesino’s huts in a clearing shortly after the track started, but then nothing more.

We’d never quite been sure what we were going to find, but let’s just say it didn’t start well. Keeping the bikes moving uphill was a 100% effort from the get go, with an uncompromising steep, rocky and muddy track steadily gaining height. It was rare that we could just walk easily with the bikes. We were carrying three day’s food – stretchable to four – so the bikes were fairly heavy.

In places the original quality of the Inca road was evident, with robust granite steps and paving stones. While at other times it was a swampy mess.

The forest was mossy, dripping wet and we saw few flat spots big enough for a tent. Not knowing what might be coming up over the following days we wanted to keep going steadily until sunset and then stop and camp, but well before the sun dipped it was already getting gloomy. We passed one tempting tent site beside a stream, but decided to keep going. When it was nearly dark I spied some mossy sticks propped up in a gap where a side track passed between two boulders. Curiosity — or was it desperation — got the better of me and I followed a muddy path down to a stream, which was spanned by an ancient fern covered log bridge. The bridge led to a sizeable clearing and a wooden hut. I cautiously rapped on the door with cold knuckles. No reply.

The door was unlocked, so I pushed it open and peered into the darkness, seeing a cooking fire, pots and pans, two sleeping platforms and piles of potatoes.

By the time I went and brought Hana back to the hut it was dark. We decided to cook on the porch, out of the rain at least and wait and see if anyone turned up.

No one did, so we helped ourselves to one of the platforms inside and slept a peaceful night inside as the rain pattered on the tin roof.

The hut was made from rough sawn local timber and sat on a foundation of large, neatly cut blocks of granite. It didn’t look like the work of a pioneer and we wondered if perhaps this was once an Inca guard post or small temple. I read later that other such remnants of steps and buildings have been recently discovered in the same valley.

We left soon after day break and got back into the hard uphill progress with no warm up, sometimes carrying the bikes, sometimes pushing.

We were only averaging 100-150 metres vertical per hour, but eventually broke out of the forest and onto the tops, but by then it was raining steadily again. So it was overpants and hoods on, and later gloves. Our cameras spent much of the time in their dry bags, and it’s moments like this we’re grateful to have a GoPro in its waterproof case to still capture a few shots and video clips with.

The crumbling remains of an old stone hut provided some shelter from the wind and rain while we ate lunch. We even made some coffee, which is rare for us at lunchtime, but we were desperate to warm up a bit and get some more energy.

We pressed on for the rest of the afternoon, making very slow progress up the swampy and rocky trail. By this stage it was discontinuous, sometimes vanishing all together. In my mind I briefly debated whether to turn back — maybe in a moment of low blood sugar — but by this stage we’d climbed over 2500m from Santa Teresa and I couldn’t bear the thought of undoing the hard work.

There were two motivators: our atmospheric mountain surroundings, amplified by our sense of solitude; and the hope that once we were over the highest pass, Abra Mojon (4500m) we’d have a blissful, rideable descent. There had to be, as reward for our persistent trudge up the mountainside.

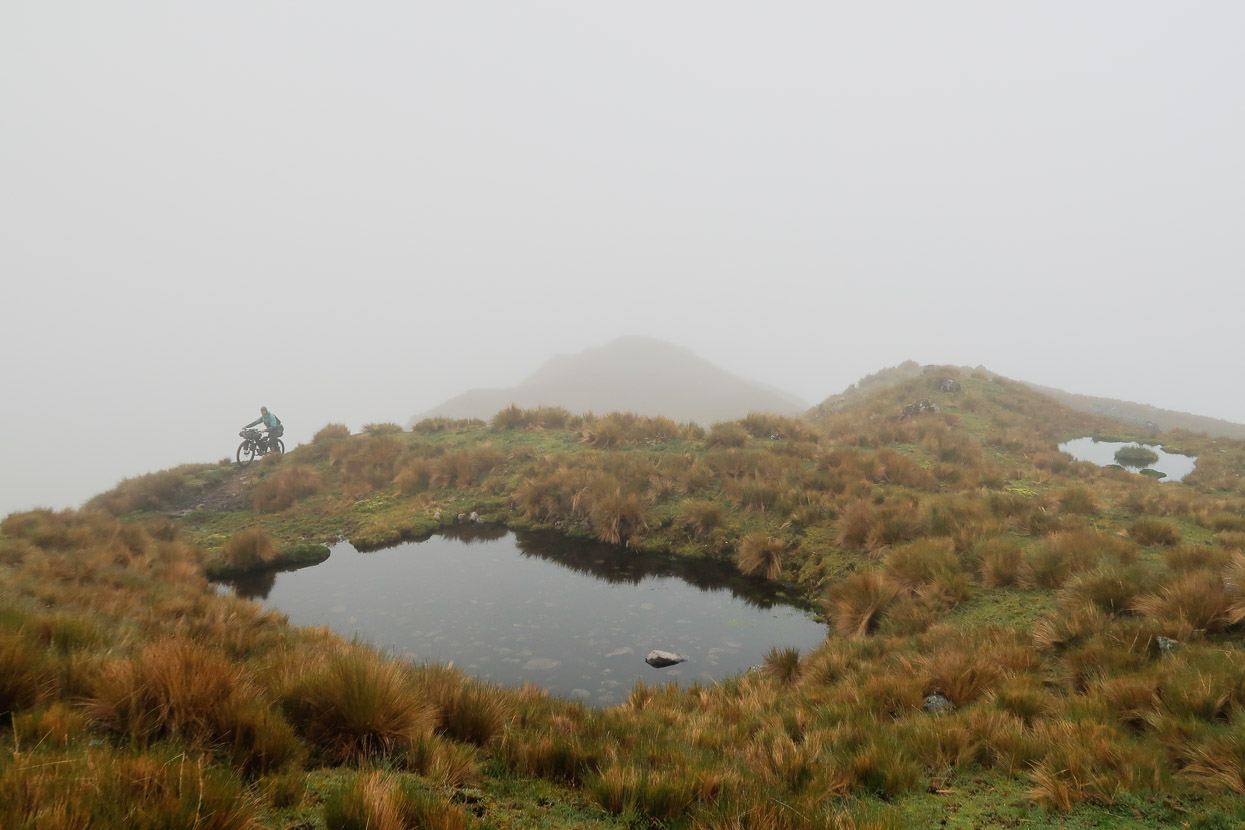

After a long afternoon a series of small tarns and some flatter ground provided a tempting campsite so we stopped to camp at 4300m. We’d covered only 7km and about 800 vertical metres that day.

The tent was pitched in drizzle, which eased off while we cooked inside, and after dark the sky cleared completely. In the distance we could make out the white massif of Nevado Salkantay, which we’d passed close by just a few days earlier. Stars twinkled overhead and it was looking promising for the next day.

Behind camp we could see in the direction we were headed, towards the rocky peaks outlying the glaciated mountains of the western cordillera.

By morning the clag and rain was back and the trail steeper and rockier.

These peaks are just a tad under 5000m and beyond them lie a series of ice capped mountains between 5000–6000m. We were starting to get the views we sought, between mist and heavy showers.

Abra Mojon, the highest pass on the crossing, felt like a real victory, but we couldn’t relax yet; there were several more kilometres of undulating country and two more 4000m+ passes before we began descending proper. We dumped the bikes and traversed around the peak by the pass on foot to check out the view.

We continued in steady rain, not dropping below 4300m while we crossed the next two passes: Tullutacana and Yanococha/Pumaqasa. Along this rolling section the track became a bit more rideable, for short bursts, picking our average speed up a little finally.

We passed laguna Soyroccocha (may have another name) and dozens of smaller tarns, all filled to overflowing with the incessant rain. There were constant streams and rivulets of water, flowing down the track, coursing over the tussock and beginning their long descent to join the big rivers that feed into the Amazon. The smaller laguna of Yanacocha (photo) is a beautiful spot, but we were cold and wet and didn’t linger there. Passing this laguna meant we had just one more short climb before the descent to Racachaca.

Our hopes for some sweet alpine single track were not answered sadly, and instead we bumped and skidded down a rocky, water saturated track. It was rideable in bursts, but wasn’t a lot of fun; more like survival riding. In the dry, on a very lightly laden suspension bike it would be more of a blast. The first 900 vertical metres dropped us down to a pampa (valley flat); low enough that the small streams from higher up were now raging, brown, flooded creeks. We crossed the biggest one on a bridge so rotten and dodgy that it probably would not survive another loaded mule on its boards. If the bridge had been impassable we would have been stuck until the rivers subsided, which given it was still the wet season, could have been days.

We crossed the pampa on sodden single track, glad to be riding a bit more and then dropped a further 600 vertical metres, stopping to eat some food at a deserted casa. Near the bottom of the descent we peered through the rain and could see the hamlet of Racachaca at the confluence of our unnamed stream and the Rio Marampampa.

The hamlet was just a collection of scattered, ramshackle huts and casas with no one in sight. We were looking over one of the stone walls, wondering if we might find shelter there when a poncho-clad man appeared along the track. When we asked for shelter he gestured towards a nearby hut and then helped us lift our bikes over the stone wall. The dirt floor of the hut was covered in potatoes, which we rolled aside to create a sleeping space and settled in for the evening. Luxury when the only other option is a soaked tent.

As with the previous two evenings, dusk brought a slow clearance and we snuck a few glimpses up valley between the wafting mist. The Rio Marampampa drains the northern aspect of Pumasillo (aka Saksarayuq, pictured below), OSM indicates the summit at 5850m, while most online records claim 6075m. The range itself is part of the Cordillera Vilcabamba, which includes Nevado Salkantay, but this group of mountains is known locally as the Cordillera Pumasillo or Sacsara. The name Pumasillo means puma claw. This range was unmapped until the 1950’s, such is the enigmatic nature of these mountains; deep in the ranges and not visible from any towns.

The weather pattern, sadly, continued and despite a clear evening we woke to rain and the valleys filled with mist. On the upside, it was mostly rideable as we headed down valley towards the final climb that would get us over to the town of Huancacalle. We’d planned three days for this leg, and it was now day four, so rations were scarce, but we could already smell the lomo saltado that awaited us in town.

Sometimes we followed parts of the original Inca road, bumping along the large blocks. At one stage we passed a small ruin, just a small building that may have been a house, but it looked much older than a colonial construction. In the pouring rain we investigated and in one wall we could see three trapezoid-shaped niches — one of the most distinctive features of Inca architecture.

Our Inca road turned away from the Marampampa and began a 500m climb towards our last pass, which was just over 4000m. It started gently, rideable even, but then turned into a slog-fest of steep pushing once again.

We were very happy to reach the top.

A 1000m descent awaited, and a pretty good one it was too. The surface alternated between smooth mule trail, rocky Inca road and the odd rock garden or stream to keep us on our toes. Not worth three days of pushing our bikes for, but fun. In places we could see sections of 500 year-old Inca-built retaining wall, still doing its job today.

The only person we saw on the way down was on his way into Racachaca with supplies, and after we got talking it turned out it was his potato shed we’d slept in! It was nice to be able to say thanks and pass on how grateful we were for the shelter.

We wasted no time in Huancacalle and went straight to the restaurant for a late almuerzo. Hot soup and fried trout never tasted so good. We were back just three hours later and ate another whole meal.

The Sixpac Manco hospedaje is the place to stay in town and is owned by a lovely old couple (the Cobos’) who have lived in Huancacalle all their lives. They’ve run the hospedaje for many years and its been a shelter for many trekkers over the years coming off the route we did, or the Choquetacarpo Pass, which takes the next major valley west of our route.

People also come here to visit the nearby Inca ruin of Vitcos/Rosaspata, which was our plan for the following morning, but not before we’d eaten a fine breakfast in the Cobos’ kitchen.

The impressive hilltop site of Vitcos is just a one hour walk from town. Designed to be defensible, it sits on the end of a long ridge with steep sides that drop away into the valleys to either side.

When emperor-under-siege Manco Inca fled Cusco after the city fell to the Spanish in 1537, he and his forces fell back first to Ollantaytambo and then further northwest again, to the lower elevated Vitcos. In surrendering Ollantaytambo the Inca relinquished all control of their highland territory — their heartland.

The origins of Vitcos aren’t clear: some sources say it was built before Manco Inca’s time, while others say Manco and his followers constructed it, expanding on an earlier site. Either way it was not held for long before the Spanish caught up and drove the remaining Inca elite to even lower elevations at the edge of the Amazon, where they established a Neo Inca state in hiding. And that site, Vilcabamba/Espiritu Pampa, was our next destination.

The archaeological complex of Vitcos is quite large, and just a 15 minute walk downhill from the main citadel are tiers of agricultural terraces and an ancient aqueduct, still functioning.

But the main feature of this sector is a huge boulder known in English as White Rock, or locally as Yurac Rumi. This boulder is thought to have been a major worship site and has several features that align with cardinal points and the solstices. The stone work is quite incredible: precise and perfectly done.

Just a couple of day’s riding remained and we’d be at Espiritu Pampa.

donations are welcome!

Web hosting, our Ride With GPS subscription and creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs and is time consuming. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Hi Mark,

after getting no response to my question “Is this going to become a mountain bike tour?” this route description is not a real surprise ;-). Despite the weather conditions these are excellent photographs again. I am glad to see my added path track matches your GPX track quite well, so it was worth the effort to improve the map. I just added the names for Racachaca and the Laguna Laccococha, which has two different names. May be you could clarify if it is Laccococha (GPX-track waypoint) or Yanacocha (Text).

Keep riding on and cheers to Hana as well

Guido

Hello and thanks Guido! Yes, sorry I didn’t reply but we had little internet those few weeks. I really appreciate your attention to the OSM details and I think will begin to add map data myself because we discover so many places lacking information in Latin America. That whole region is very poorly mapped in OSM and Google. I’ll try and figure out for sure the names of the lakes, and I’d also like to confirm the other two named passes, but it’s a lot of detective work! Thanks, Mark + Hana.

Hana & Mark, this last trip sounds like you may have experienced a couple of sobering encounters; “We crossed the biggest one on a bridge so rotten and dodgy that it probably would not survive another loaded mule on its boards”. I was somewhat uncomfortable in hearing about your fall (only a broken brake lever) and thinking of the many other encounters you haven’t mentioned. Your adventures do amaze me and I’m sure hundreds of others, and I’m sure to speak for all…. ‘be safe and no broken bones’.

kind regards, vic & joy

P.S. So, where does one get to peek at your videos?

Thanks Vic, yes comes with the territory I suppose. We’ve been very lucky to have no major injuries in three years. Just some stitches in my elbow after I fell down some stairs! We do try to take it easy, but as they say: ‘shit happens’ sometimes.

We don’t post a lot of what we shoot video wise… it takes enough time working on the blog, but there are snippets in two recent posts. I’m hoping to work on something longer from our recent adventures if I can make the time!

cheers.

Epic, and very wet! Love your find of a shelter on the first night!

Yes, we were very grateful for shelter on the 1st and 3rd nights – especially the 3rd when we everything was soaked and we were cold and wet! Any port in a storm!

Guessing, we may not see that hike-a-bike route on bikepacking.com 🙂

Haha – no, we’ll keep that one low key and reserved for the masochists! I did include the GPX at the end of the post just in case someone’s keen enough!