First days on the Trans Ecuador Mountain Bike Route.

Only a few days in and already Ecuador has been a remarkable ride: challenging, remote at times and full of surprises. Even only a short distance from the border we felt like we were throughly in a new country.

As I write this post we have finally crossed the Equator. Reaching this point is one of those equally meaningful yet arbitrary moments on a journey. Being on rain soaked backroads there was no monument announcing our traverse of this imaginary line around the globe, instead the latitude reading on the GPS hit zero, and then began gradually climbing towards 1 again.

Considering we started at 71 degrees north, over a week’s riding north of the Arctic Circle, it has been a good moment to finally hit zero, the centre of the tropics; although at 3000 metres in Ecuador it hardly feels like it. While the daytime sunshine can be intense, we haven’t seen much of it as the cloudy skies, mist and frequent rain have kept things damp for the most part. I think we got our timing right though; had we been here a month earlier – during the peak of the wet season – some roads would have been impassible with mud and the rain persistent.

We’d heard of long hold ups at the Colombia-Ecuador border due to the massive influx of refugees escaping the crisis in Venezuela. 37,000 people a day are reported to be crossing into Colombia (via legal borders) and then many move further south to Ecuador and beyond in search of work and better living.

We’d been tipped off that the fastest strategy for exit/entry was to arrive around 9 in the evening to exit Colombia and then proceed to Ecuador to get a visa stamp, before returning to Ipiales, Colombia for night. This worked quite well and there was no queue for the Colombia exit stamp, we then proceeded to the Ecuador entry line which extended for 200-300 metres outside and around the building, with crowds of people and piles of luggage cramming the entry area. While we stood in the line a policeman came and wrote a number on our hands, marking the limit for that day’s entry. The line moved faster than we expected though and in three hours we had a new stamp in our passports and caught a cab back to town for a few hours sleep.

The following morning we rode out of Colombia and into Ecuador without a check. Quick and easy and no eight-hour waits.

We just went as far as Tulcan the first day, we had a couple of parcels to courier forward; spare tyres and chains to Pifo; and some other odds and ends and extra clothing to near the Ecuador-Peru border; as well as some other admin to take care of before finally hitting the Trans Ecuador the next day.

Changing our remaining Colombian Pesos was one of the things on the list, to US Dollars; Ecuador’s official currency. Mixed with the greenbacks though are Ecuador’s local coins as well as coins now out of circulation in the USA.

Tulcan’s cementerio municipal was one of the more unique cemeteries we’ve wandered into with its immaculate topiary, which has transformed the garden’s trees and hedges into all sorts of creative creatures and forms.

This style of ‘hi-rise’ cemetery is very common in Latin America, although this expansive place had large family tombs and earth plots as well – all depending on the wealth of the family.

A declaration of strength by the Ecuadorian military outside their base on the outskirts of town.

Right out of Tulcan we were onto the Trans Ecuador Mountain Bike Route (dirt version), a 1381 kilometre route that traverses the high volcanic chain of the country. We’re intending to combine this route, with the more technical single track version in places, along with the Los Tres Volcanes route. These three routes together will get us close to Peru.

The Trans Ecuador soon leaves town behind, climbing on an ever diminishing dirt road past potato fields and ever upwards towards the cloud shrouded páramo.

Only two hours ride out of Tulcán we were into the páramo. Moody, rain saturated and wide open. Clouds blackened overhead and sprinkled us with rain, but it never quite closed in.

The sudden lack of people was almost alarming; instead a stony road through rolling páramo that’s covered in frailejones. The contours of the land are already relaxed, but the frailejones dotted over the landscape lend it a unique softness. It reminded me of the Central Otago tussock country back home.

It had been early afternoon when we left Tulcan, so it was nearly dark when we arrived at the guard station for the El Angel Ecological Reserve. The one ranger in attendance kindly offered us a spartan room and a mattress inside the building for the night, which was a pleasant surprise considering the drizzle. We cooked a simple dinner while the skies cleared to a starry night and distant lightning crackled in the sky.

Dawn brought rain showers, but soon it stopped and we made the short walk up to the mirador just above the ranger station to this amazing view over the Lagunas El Voladero. It was one of the few times since Alaska we’ve been able to look out at an expansive landscape and see nothing man made. It was a beautiful, ethereal place as the mist came and went.

With a backdrop of spectacular Volcan Cayambe (5790m) the road dropped away from the Paramo de las Lagunas and down to the village of El Angel.

After second breakfast in El Angel we rode on to San Isidro.

Where a mountain bike race had just finished, and a fiesta was just just getting started – kicking off with a ceremonial parade, celebrating the village’s diverse cultural roots and religion.

After a half hour of unexpected entertainment (we love those kind of surprises), we pedalled on, climbing up and around the side of Cerro Iguán on dirt and, as we are coming to realise as ubiquitous in Ecuador, a road made from river cobbles.

We dropped off the side of the cerro and dropped into a long, long descent down grassy farm tracks, more cobbles and finally porcelain-smooth pavement as we dropped from 3400 metres down to 1300 metres. The scale of the terrain here is phenomenal, and by the time we reached the valley floor we’d entered a much drier environment of scrubby plants, cactus and sugar cane.

Estación Carchi, sweltering and run-down on the valley floor. Interestingly most of the people living at lower elevations in this giant valley are of African origin, much like the people of the Caribbean. Just a small pocket of a completely different culture.

Due to security issues surrounding the village of Buenos Aires (problems with illegal mining apparently), it’s not currently recommended to cycle that section of the Trans Ecuador, climbing into the páramo surrounding Cerro Yanahurco, so we detoured at Estación Carchi and followed pavement to the sugar cane town of Salinas – also populated by Afro-Ecuadorians, where we spent the night in a basic guesthouse.

There we joined the TEMBR singletrack route (at the recommendation of Cass Gilbert), as a means of accessing the Cerro Yanahurco páramo. It’s a long and steady climb just to gain the singletrack section of the route and we spent most of the day climbing 2500 vertical metres through farmland, small towns and narrow roads as they steadily wound higher into the mountains.

Through Cahuasqui, sitting on its distinctive river-worn plateau. The landscape here is entirely volcanic – much of it dense tephra from past eruptions that has been eroded by river and rain fall creating steep valleys, canyons and sometimes daunting terrain.

The last village on the line, San Francisco.

This Coca Cola sign was the only clue as to the presence of a tienda in the village. Our knock on the door was answered by a shy young girl, maybe not yet in her teens, who had probably not seen a gringo before. We bought a bottle of coke (of course) some biscuits and some chips – scraps left from an apparently minimal inventory.

We rode on, up grassy tracks, enjoying finally being up high again.

At about 3250m the road ended and a muddy trail started. We rode a short distance and then mostly pushed another 200 vertical metres to a prominent grassy knoll and flattening in the ridge, where we camped.

A small mud brick casita occupies the top of the hill, although we never met its resident.

We were aware that the following few hours of travel to the páramo was a notoriously hard hike-a-bike, and from the minute we left camp the hard graft began. Our loads are pretty light for long distance cyclists (my camera gear makes the bulk of my total weight), but not the minimalist short-term bike packer weight that is ideal for this sort of pushing and carrying, so it was a solid and – for the most part – unrelenting effort making progress with the bikes. The mud didn’t help.

We tried various techniques, depending on the width of the trail and the amount of rocks, but straddling the bike and shuffling it forward often worked well!

After a long morning we finally reached the bushline and got a better appreciation of our surroundings. Hard earned – but a beautiful place to be.

The route followed an ancient trail known in the Andes as a chaquiñán; a historic footpath used for trading and tending stock in the high country. In places it was eroded deeply into the hillside by the passage of time.

Lunch and water refill on the edge of the páramo.

and onwards…

After about eight hours we finally hit a respite from pushing and lifting the bikes, when we reached a flattening in the ridge at about 3900m and got in a few dozen metres of riding, passing a small partly-derelict hut (useful shelter in bad weather with water nearby).

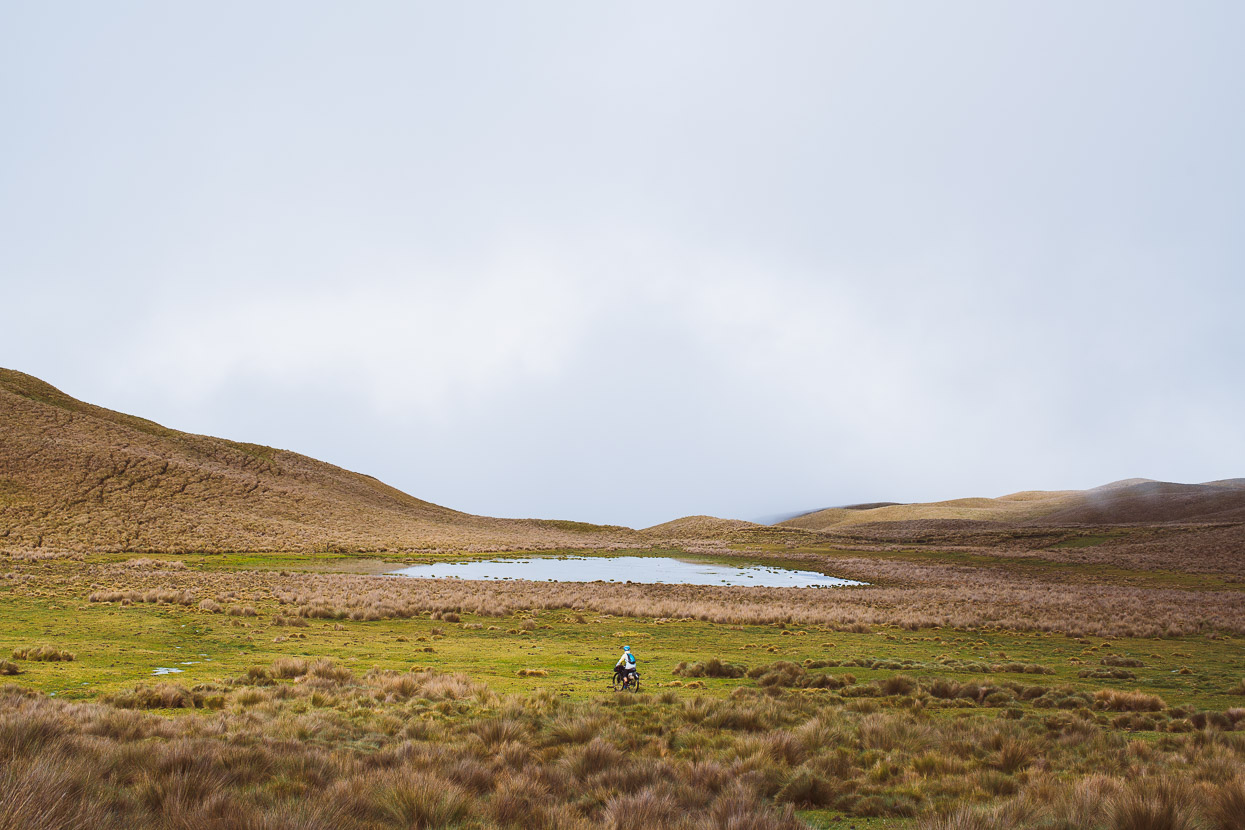

We left the hut behind as we started pushing through the now tussocky, tangly, pedal catching páramo. Of course as soon as we left shelter the afternoon storm rolled in bringing hail and rain.

We could easily have been pushing our bikes in the Central Otago, New Zealand, high country.

Between bursts of rain we grovelled higher, now feeling the long day, as the route splits into lots of rutted, muddy discontinuous trails through the tussock. It was slow progress.

The main climb topped out at 4075m and we scuttled down hill briefly to a small tarn and pitched the tent during a lucky pause in the rain. It had taken us 10 exhausting hours to cover 7.4km and 760 vertical metres – definitely a record for least ground covered in a day during our nearly two years on the road. Was it worth it? We wondered while we pitched the tent surrounded in mist and hustled inside, wet.

I woke during the middle of the night to pee, and opening the door of the tent saw that it was completely clear, crisp and bright as the milky way stretched overhead – visible horizon to horizon. The tarn sparkled, reflecting the sky and Cerro Yanahurco stood, craggy and dominant, just beyond camp. It was exceptionally beautiful.

We woke early and ate in the twilight while a muted dawn was eased into life as the sun slowly rose, saturating the sky with colour and turning the tussock a brilliant orange.

We could feel the physical effort of the previous day in our bodies as we got up and walked around the tarn, in awe of the morning and feeling massively appreciative of where our efforts had taken us. It did feel worth it. We lingered, not wanting to rush away.

But soon enough the mist closed in again as the cloud boiled up from the deep valleys in the warming air. We still had a few kilometres remaining to reach the road. The toil through the tussocks continued.

But we were gifted with some some amazing views.

The finale of this somewhat epic section of the TEMBR Singletrack route is a two kilometre stretch of gentle downhill, though a swamp. But about half of it was rideable, as our tyres sank a couple of inches into the red goop and then found traction.

Even at 4000m, pedalling off uphill on the very welcome road felt easy compared with the grovelling of the hours and days before. It had taken us a further three hours that morning to cover the final five kilometres to the road, which we joined at right/centre of this photo. The triple peaks of Cerro Yanahurco in the background.

The road we joined brought us back to the TEMBR dirt-road route (south of the Buenos Aires township) and we followed that route onwards towards Otavalo, where we took a welcome rest day.

Part of the route to Otavalo follows an active water race, crossed in a couple of places by these skinny water bridges. The force of the water is enough to push you through without pedalling.

Otavalo made a nice break for a day to recover from our hike-a-bike efforts; good food, nice surroundings at the Valle de Amanacer Hostal and a big market with handcrafts in abundance. It’s a touristy town, but a nice one. We had a relaxed morning, drinking great coffee with a couple of other south bound cyclists, Nancy & Dave, who’ve reached here in one year, starting from Fairbanks.

From here we’ll continue on the TEMBR dirt road version for a couple of days to Tumbaco and Quito and then onto the Los Tres Volcanes route.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

So that’s where all the US dollar coins go! There have been several different designs of US dollars coins issued in the last few years, but after a couple months they seem to be rarely seen stateside!

A couple of these photos remind me of the Lindis Pass………but I think you’re crazy !!!