The Trampolín de Muerte.

This leg, our penultimate in Colombia, has taken us from the coffee-laden volcanic hillsides of San Agustín through some of Colombia’s least inhabited country to Mocoa and then on to Pasto via the notorious Trampolín de Muerte ‘highway’.

I put highway in quotes, as this vital Andean connection between the cities of Mocoa and Pasto, in two different departments, is unpaved, barely more than a vehicle’s width much of the time and is regularly victim to the region’s very high rain fall, which frequently causes landslides and flooded creeks.

Literally hundreds of people have died in accidents on this road over the years, but despite such bleak prospects this narrow ribbon of road has become something of a rite of passage for cycle tourists in Colombia, and for good reason. It’s not often in Colombia that it’s possible to completely escape cultivation, farming and human habitation, but the landscape of the Trampolín de Muerte is so steep and untameable and the rainfall so persistent, that few people have ever made this beautiful stretch of mountains home. That makes for a classic ride through some impressive unbroken wilderness.

We left San Agustín in rainy weather that set the theme for the following few days (the rainy season had to catch up with us sometime), but the warmth increased as we dropped down through the mountains, catching some final glimpses of the Rio Magdalena on the way.

Granadilla (a sweet passionfruit) is grown in abundance here. Cheap and plentiful, they’re one of our favourite snacks. From San Agustín we dropped down towards Pitalito and then short-cutted across to Bruselas. There picking up the practically deserted, but paved, highway 45. This is a good direct mountain road straight through to Mocoa.

The afternoon brought steady rain and we continued until near dark to a tiny restaurant/truck stop, the La Bota Parador, a few kilometres before San Juan. These places don’t normally offer accommodation, just food and coffee but when we asked for place to camp nearby the owner offered us a room for a few dollars, so we squeezed in with the empty beer bottles and had a cosy night.

Mist clung to the forested hills in the morning as we continued along the edge of the Cueva de los Guacharos National Park.

We saw various cableways along this section of road, used to bring harvested crops across the steep valleys.

The city of Mocoa is isolated in a lush jungle-covered valley – at the toe of the Andes – just a few kilometres from plains that stretch into Brazil and the Amazon. It’s right back down at 600 metres – fully tropical again after the cooler climes of San Agustín.

The city made international headlines last year when over 300 people were killed by a landslide when the valley’s main rivers the Mocoa, Sangoyaco, and Mulato all flooded after an exceptionally heavy rain event. Rivers descending from the Andes in this region have exceptionally steep drops; often from 5000m to 500m in only 50–100 km. Consequently they collect boulders and debris, making floods more dangerous and flash floods more likely. This mural is one of the city’s memorials to the victims.

The big Rio Mocoa descending towards the plains, where it joins other broad rivers for a long journey east as the Caquetá, eventually joining the Amazon.

We’d planned to head straight onto the Trampolín de Muerte from Mocoa, but word of some nice waterfalls tempted us to spend an extra day. We didn’t need much convincing to stick around – especially as it’s the last of low elevations and jungle we’ll see for a while.

We found an excellent place to stay 6 kilometres out of town and across the Rio Mocoa, near the entrance to the Fin Del Mundo waterfall track. Posada Etnoturístico Achalay is run by the local indigenous population and is set up with a basic rooms and cooking facilities. There’s also covered camping. We had a great open air room in the top of the treehouse.

In the afternoon Juan – a very likeable guy who runs the posada – offered to guide us to the evocatively named Ojo de Dios (Eye of God) waterfall. For NZ$10 we walked with Juan for around four hours. He pointed out various traditional plants as we followed muddy tracks up through the jungle, crossing small creeks in the steep sandstone valleys.

After about an hour we emerged at a cirque-like cliff, from which the beautiful Ojo de Dios issues from a hole in the roof capping the sandstone walls. It’s a magical spot; with sparkling droplets of water pouring off the edge of the roof and shafts of light penetrating the trees; the forest around us growing lofty and narrow to catch the sun. We could have lain around here for hours.

On the way back we stopped at another taller waterfall – Arcoiris (rainbow) – which has a perfect ledge to stand on under the relentless curtain of water.

The following morning we walked to the Fin Del Mundo waterfall (8km return). The number one tourist attraction in Mocoa, this waterfall is a (sadly) more commercial operation than the low key walk we went on with Juan. There’s a 15,000 COP entry fee, and safety/security personnel along the walk, which climbs up through regenerating forest before dropping down a hill and following a beautiful stream as it courses over a number of cascades and under a natural bridge.

The falls are well named; you round a bend in the stream, and there the sandstone stream bed ends suddenly and the water plunges into a 70 metre drop, before continuing steeply down a jungled gorge. In the distance Mocoa is visible surrounded by the verdant foothills of the Andes. It’s a cool place.

Back at camp by 11am, we packed up and hit the road – with El Mirador (1500 vertical metres higher), near the top of the first major climb of the Trampolín, our goal for the night. It was raining by now of course – and obviously had been for some time deeper in the mountains, judging by the state of the Rio Pepino. We stood here for a while, listening to roar of the river and sound of boulders being tumbled on the riverbed.

This and the following seven shots were taken with our GoPro (waterproof housing) – a handy backup when it’s too wet to get my Sony out.

It poured continuously for the first hour or so and we just rode in t-shirts, soaked to the skin but comfortable in the tropical rain. We stopped at a small restaurant, already 500 metres higher and cooling off and changed into dry tops and jackets, ate some eggs and rice and continued up the narrowing road.

We wound our way steadily up the road, already a rough bed of stones, but framed the entire way with lush forest and atmosphere in the mist and rain. It was Sunday, so traffic, which is mostly trucks and collectivo (shuttle) vans was occasional but not busy.

We reached the one notorious ford on the Trampolín to find backed up traffic, some of which had been waiting an hour. The stream was swollen and dirty, churning over the rocks and no one yet had been tempted to give it a shot in their vehicle. We had our timing right though: not long after we arrived, the biggest truck decided to give it a crack, and it was clear that the depth had already dropped quite quickly.

Others followed suit – the drivers keen to show off their bravado. some taking a couple of goes to get through the deepest bit.

Then it was my turn with the panniers, and we both carried the bikes over one at a time.

Lots of switchbacks keep the grades reasonable as the road snakes its way around ridges and gullies.

The rest of the fords were rideable, but I can imagine them also being impassable at times.

Finally the rain stopped and the views opened up, looking north east into the Mocoa Valley and the mountains we’d come over on highway 45 from San Agustín.

Surrounded in lushness, little infrastructure, no development; a perfect touring route.

Except for the odd surprise… We saw trucks make perilous reversing manoeuvres sometimes to allow another to pass.

Finally gaining some real height on the 25 kilometre climb.

With the hold up at the ford and the multiple stops to just go ‘wow’ and take photos we arrived at El Mirador’s tiny restaurant about half an hour after dark, probably surprising the police on guard on the edge of the hamlet. Hot agua panela never tasted so good. We got refills too.

And the tiny comedor turned out a pretty good meal of chicken, rice, patacones and potatoes – the typical ‘meat and three carbs’ Colombian diet. As we finished eating a contingent of heavily armed police walked in from the station just down the road for their evening meal, casually setting their assault rifles down on the tables and tucking into plates of rice and chicken.

After some asking around (there’s a dearth of suitable camping spots at the Mirador itself), we pitched our tent on the porch outside a disused storeroom and toilet.

We rose early to catch a moody dawn breaking over hills beneath.

The police were up too, on watch. Here to guard the communications towers and monitor this key road link.

North east along the edge of the Andes towards Mocoa.

And south east towards the plains that stretch into Amazonas.

Our camp and the noisy fellow who woke us up at 4am.

Two kilometres more climbing in the morning took us to the first pass and another tiny settlement of four or five buildings. There was a small tienda selling hot food so we had an early second breakfast in the company of a motorcyclist and a hungry chicken.

We noted that there are a couple of other places to eat past here and then nothing until a small village with a cafe/restaurant on the climb to the final pass before San Francsico (+33km from El Mirador). They’re noted here:

El Mirador: Restaurant and tienda (open 7am – 8pm). Tricky camping.

+ 2km: Restaurant and tienda. Camping space (with permission).

+ 5.5km: Abandoned building with flat camping, near streams.

+ 7.5km: Restaurant and tienda + camping space. Friendly.

+ 18.8km: Closed restaurant but possibly camping.

+ 21km: Good hidden grass campsite behind ruined building.

Deeper into the hills we ride.

The road drops, and then climbs steadily again…

More weird and wonderful creatures…

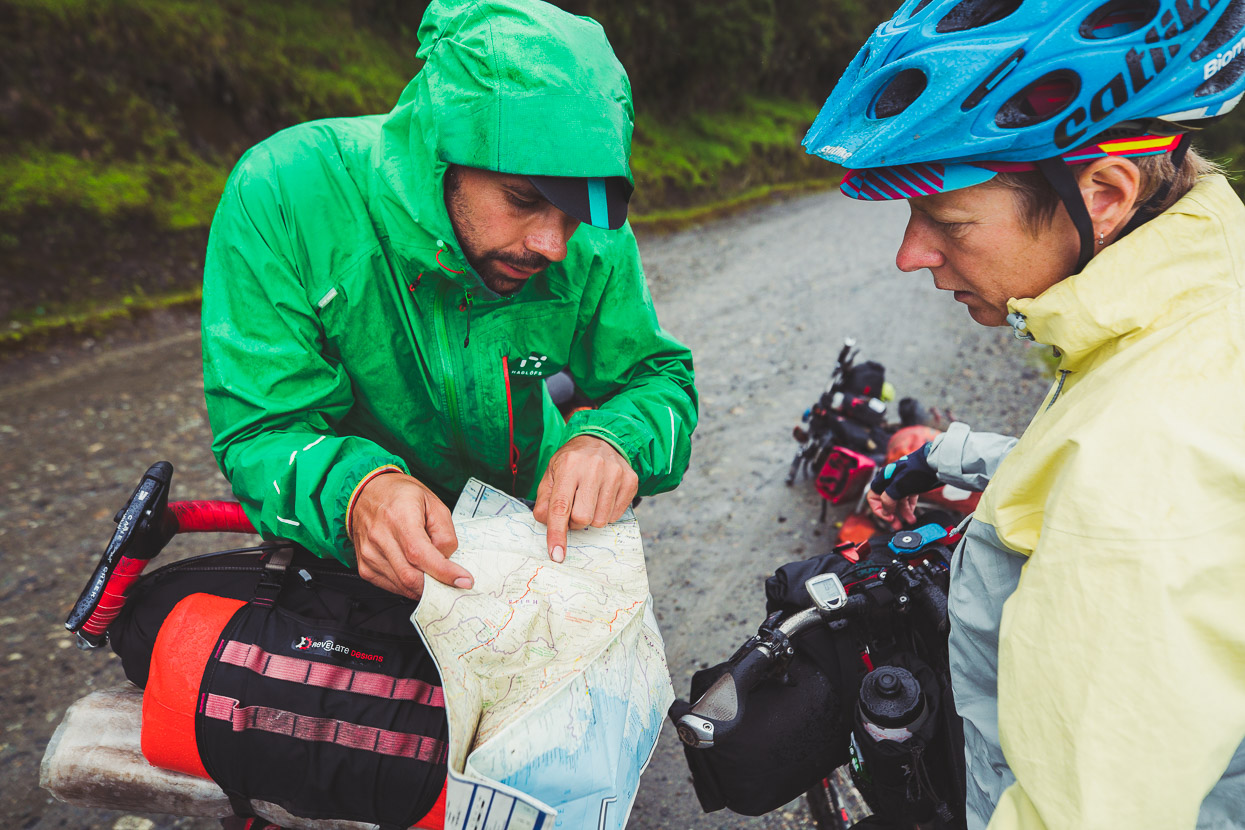

Just after we crested the last pass in the rain we ran into Raul (Spanish) and his companion from Bogotá (whose name I forget). Raul’s headed to Mocoa and then southbound, bypassing Ecuador to get to Peru, having already ridden the Trans Ecuador northbound. Always great to see fellow cyclists. Hopefully we’ll see Raul again in Peru.

And of course the inevitable exchange of info for the road ahead.

The road turned to pavement and we zoomed downhill into the broad Sindamanoy Valley, suddenly back among grazed land, crops, fincas and people. We spent a night in a cheap hospedaje in Sibundoy and the next day rode on towards Pasto on smooth and quiet pavement.

Pavement it might have been, but the climbing continued, higher still. At the top of the 1000m climb out of Sibundoy we found ourselves in misty paramo and surrounded by the ever interesting frailejones.

A blissfully smooth and fast downhill dropped us close to the edge of Laguna de la Cocha.

And then over a final climb that dropped us into the mountain-ringed patchwork basin of Pasto – just under 100 kilometres from the Ecuador border.

Pasto’s not the most attractive city in Colombia, but as always with travel it’s nice to experience the contrasts and it was an interesting and lively place to be after the small towns and isolated roads of the past couple of weeks.

We found a good hostel to settle into for a couple of days while we gave the bikes their first proper clean and service in four months. With only two days left to the border with Ecuador our next post will be a brief one!

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Fascinating as always !