22 days on Cuba’s Ruta Mala Bikepacking Route.

We’ve been two days on the Ruta Mala now. Yesterday we put in a good day, starting in Santiago de Cuba and riding fast pavement on the coast and then a narrow, windy dirt road into the mountains. We’re enjoying our first taste of cycling here, but we have quickly realised how different things are in Cuba. Really different. And it seems no previous cycle journeys – not China, South East Asia, Philippines or Central America – has quite prepared us for travel here.

People have been friendly – generous even. We stopped at a small panaderia to buy some bread rolls and the owner gave us an extra one free. A nice gesture, considering that most people here still collect a government food ration. There’s not a lot to eat on the road, generally. For lunch yesterday we ate the rolls and some bananas, and in the same village there was a man selling some basic donuts (just slightly sweetened deep fried flour balls) from a portable deep frier on a wheeled cart.

We turned inland and began a long climb into the Sierra Maestra – one of three mountain ranges that punctuate the flat of the Rula Mala route. These mountains were the first operating base and hideout for Castro’s fledgling revolutionary force in the late 1950s. I read that you can even still visit the hut that Che Guevara lived in.

The most distinctive feature of the landscape are the tall palms that sometimes dot the hillsides; tall, slender trunks and broad leaves that swish in the wind. They’re beautiful trees. The coast was dry, with scrub, succulents and parched hills, but inside the ranges it’s much greener.

Cuba’s coastline east of Santiago de Cuba is dotted with shipwrecks from the 19th century Spanish–American war.

We trimmed our gear for the Ruta Mala, dropping racks, panniers, laptop, cooking kit and a few spare clothes. It was nice to be light again.

We’d aimed for a big village to try and spend the night in, assuming there to be a posada of some sort, or a casa particular. The casas are government approved homestays and are the most common tourist accommodation. It was a weird agricultural town and I guessed it must have been government built for the coffee and cocoa crops grown here. We stopped for some helado (ice cream) which was served in a ceramic dish with a spoon. You could have whatever flavour you wanted as long as it was chocolate. This is a common theme when it comes to food, which is slightly disconcerting for food-obsessed cyclists.

We asked about a room, and one of the women from the helado shop ended up taking us around three different posadas spread over the rambling village and all of them turned us away. Tourists are only supposed to stay in government approved hotels (which are rare) or casa particulars.

Some people told us there was a cheap hotel about another 9 kilometres away, so we pushed on as the sun set, turned off into a side valley on a small dirt road and ended up at a ‘hotel’ that was US$70; way out of our usual budget. It was an odd place; grandiose in a mildewy spiderwebs-in-the-corners kind of way and oriented at tourists looking for a Cuban forest experience. It was well after dark now and the man on the front desk must have felt sorry for us because he invited us to come and stay at his ‘casa de campesino’ (farmers house) which was a 20 minute walk away up a steep hill. On the way, walking up the slippery track in the dark, he told us not to tell anyone, and that we could stay for ‘whatever we wanted to pay’.

The house, really a hut, was completely alone on a grassy clearing on the top of a ridge, surrounded in forest. A menagerie of animals greeted us along with the man’s wife and his young son. They were generous, considerate and caring; heating water on an open fire so we could wash and lending us their sandals to wear on the dirt floor. The woman remade the boy’s bed for us sleep in and cooked us a meal of chicken, rice and beans. In the morning they made us fresh coffee before we left. We carried our bags back down the hill to our bikes at the hotel where we’d paid a man a tip to keep an eye on them overnight.

Today was a tough one, both physically and mentally. We set off this morning to complete the rest of the trail’s section through the Sierra Maestra. We started off well, but as we left one of the small villages people began to warn us about ‘fango’ (mud) ahead.

We pushed on, not ready on only day two to turn tail at the first sight of mud, but as we got deeper into the hills a couple more warnings came from people we passed. Sometimes it’s hard to get an objective answer when we ask how bad it is, especially with the language barrier. But when a lady holds her hand above her knees to show you the level you know it’s bad. Already we were pushing our bikes in the sticky goop. We dithered for a while, looking at the map to suss out a detour. Meanwhile the lady – in ragged skirt, gum boots and carrying a homemade bag – walked off down the road. After a time she turned and shouted to us, waving her arms, urging us to turn around.

It was frustrating to have to leave the route so early in our tour, but we made our own adventure. We found a detour that still mostly stuck to dirt and skirted the range at a lower elevation. At first the hardpack was fast and pleasant and we were pleased with ourselves. But after a junction we started to see water-filled wheel ruts and soon the whole road was a series of ruts, mud and water. We walked the bikes, gingerly stepping and jumping between solid ‘islands’. Some people were walking the same way – headed to the next village – and we followed in their footsteps, chatting while we walked.

Lunchtime found us in a small town, where we were desperate to get something to eat. The only place with any food was a stand up ‘bar’ with beer, rum, bread rolls, cigars, coffee and juice. We asked if they could make us some bread rolls with fried egg and cheese (two fairly reliable staples) and they obliged.

We’d left our bikes outside the bar, locked together, but drunk men kept warning us to keep an eye on them. One man – alcohol on his breath – asked where we were going and insisted on drawing us a map, which consisted of some lines and unintelligible writing with no other points of reference. When we looked puzzled, he looked a bit angry, and several times drew back over the lines on the map to emphasise his point, while we nodded vaguely.

After some dry dirt tracks and a stream crossing we eventually rejoined the Ruta Mala and arrived in Guisa – a town that felt as if it had not left the 1950s. Horse and carriages trotted around the square and bored looking people sat under the porticoed eaves of the wooden buildings. We snacked on bread rolls with cheese (the only thing available) while people stared at us. We pushed on, aiming for a waypoint marked ‘Friendly cafe, with nice folks…’ hoping that we’d (a) find some dinner, and (b) a spot to camp. The roads were muddy again – slow – and we arrived on dusk.

We parked our muddy bikes up on the wall outside the cafe and received a friendly enough welcome, although several men were crowded around the small bar – having finished work for the day – if they did work – and were drunk on the ubiquitous white rum that seems to be the beverage of choice. ‘Horita’ (literally ‘in a little while’) was the reply when we asked about food, but we’ve travelled enough in Latin America now know horita could mean anything from 20 minutes to two hours. It turned out to be closer to the latter. It was a generally confusing situation; we still weren’t sure if we could sleep anywhere and the promise of food seemed vague.

In the meantime one of the drunk men asked if we wanted to wash at the river and seeing as we still had no idea where we might sleep that sounded like quite a good idea. We only made it 50 metres down the road when the heavens opened, so we ran with the drunk guy to a porch and stood in the dark while water cascaded off the roof. It made a pretty effective shower, so we forgot about the river and washed, clothed, in the torrents of water pouring off the roof, in the dark, with a drunk campesino. Meanwhile another older man who could hardly stay on his horse came and laughed at us, just sitting there on his horse in the pouring rain.

Eventually some food arrived, and with that an invitation from the bar manager/cook to come to her house and sleep. Our second Cuban home in as many nights. The house was decorated in a kitsch style that you could probably only see in Cuba – all doilies and lurid fake flowers. We met the woman’s husband, who just turned his head from the TV baseball long enough to say hello and later we met her son, whose room we slept in. He worked as a security guard in the nearest town. They were lovely people though and made sure we had everything we needed before we turned in for the night.

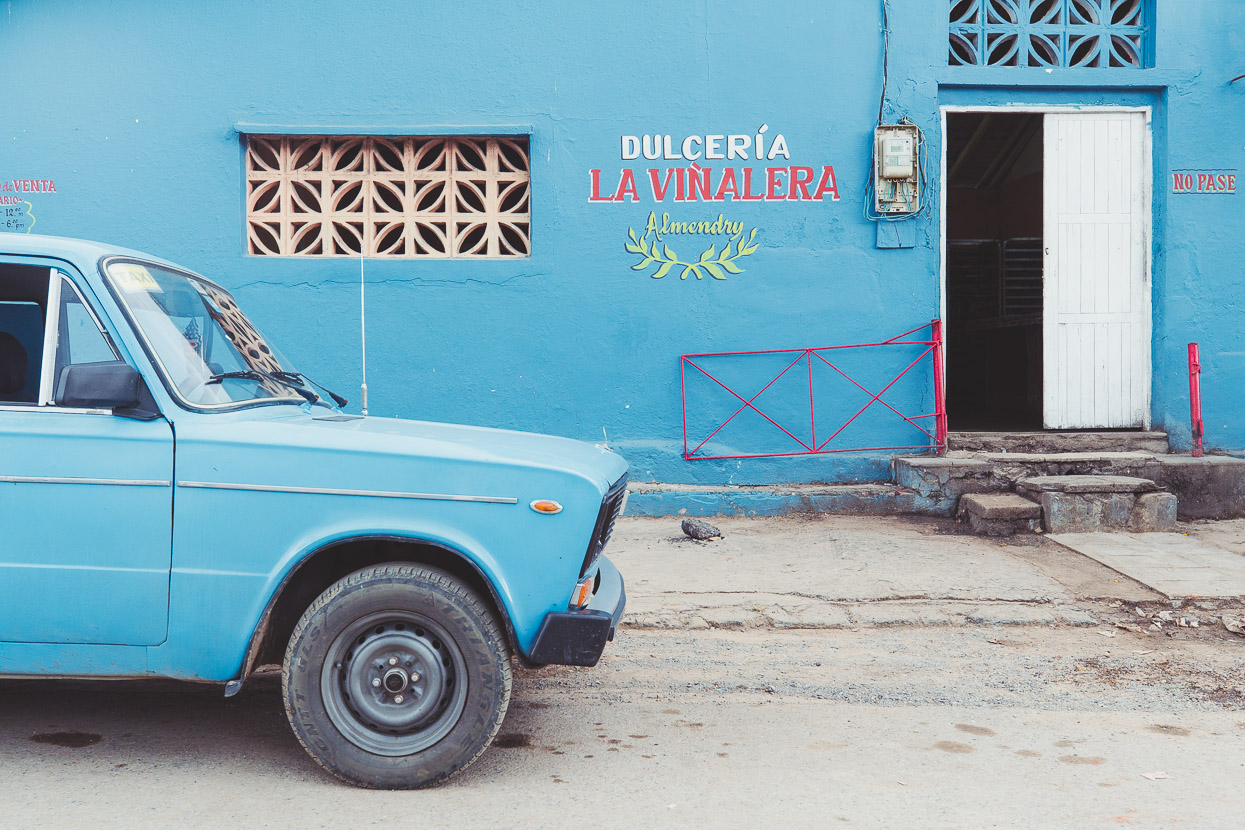

Drab socialist architecture and Russian trucks, cars and motorbikes are typical of Cuba’s medium sized towns.

After the rural riding of the first three days Manzanillo was our first Cuban City – and like Havana anywhere outside of the main plaza had seen better days.

As I write this we’re sitting, sweating in the tent. The fly is off, and the sky above us is mottled with patches of cloud that are tinged orange as the sun sets. Hundreds of mosquitos are whining their way around the outside of the tent. Earlier this afternoon I’d imagined stopping this evening at an agreeable spot, where we could catch the last of the sun and sit outside, relaxing and eating whatever food we’d been able to find for dinner. At least we have a beer each. It makes my head feel fuzzy after a long day on the bike and seems to help with the itching from the mosquito bites.

Things started to go awry this morning when we followed the GPX track down a double track that had clearly not seen any traffic in recent months. We pushed on through the thorny acacia that overhung the track, for several hundred metres and turned off into some long grass that led to a narrow canal. Before us a small steel bridge had collapsed into the murky water and on the other side where the track was supposed to go was just a wall of scrub and acacia. I decided to persevere to see if we could even cross on the bridge remains, and had just decided it looked too dicey (especially considering this area is known for crocodiles), when I nearly stood on a snake coiled on the warm metal. My heart skipped a beat and we turned tail, following an equally overgrown sugar cane access track back out to the highway.

We got in some good kilometres through the rest of the day, and reached Dormitorio, a tiny railway settlement, in the late afternoon. We’d hoped the village would be big enough for a decent dinner feed, but ended up leaving there with two beers, four bread rolls with ham and a small packet of chips to eat. We rode on for maybe three kilometres, following a rutted track near the railway lines and stopped at a clearing in the scrub. As soon as we dropped our bikes the mosquitos swarmed us and I think we broke our tent pitching record by a good minute.

In the morning we tried to carry on down the road, but it was messed up from the wet season still, with deep water filled ruts, mud and thick acacia closing in on it. We alternated between this road and a vaguer track nearer the railway lines, then then railway track itself, making slow progress. At one point we came across a worker slashing the long grass near the tracks and he offered to cut us a path back to the road where he said it would soon improve.

It did eventually, but by this time we had multiple acacia thorns poking out of our tyres. I pity anyone who attempts this route without tubeless tyres. They’re essential. Over the day the road’s condition came and went, sometimes picking our way around mud pits and ruts and sometimes rolling fast over hardback. Roughly 50 kilometres from the nearest main road, this place has a desolate peace to it. It’s dead flat, and in every direction scrubby trees and thorn bushes grow. I wondered if it was once arable land but with the collapse of Cuba has overgrown.

We spent the night in Amancio. Like many Cuban towns the tall chimneys of its sugar cane processing plant give away its location long before you reach it. Mostly the plants are now abandoned. While the sugar cane industry continues, it’s not big enough to support all the plants. Forlorn state built apartment blocks are common too, housing workers and their families. They’re spartan and depressing looking places. The standard accomodation for independent tourists in Cuba are casa particulars, which are basically homestays: a room or two in a private home where, if you wish, the family can cook for you too. They’re state controlled, and have to maintain a particular standard of hygiene and service. We like them for the fact that you get contact with ordinary Cubans, you generally know what you’ll get and the breakfasts are legendary. We usually only took the breakfasts on our few rest days and you’re usually guaranteed bread, ham, cheese, eggs, fruit, coffee, fruit juice and sometimes cake. Heaven!

Camagüey was probably our favourite city on the Ruta Mala: a rich colonial history combined with that classic Cuban 1950’s look. Long ago the city was frequently targeted by pirates so the city’s centre was made into a confusing configuration of discontinuous or angled streets to confuse raiders.

Late in the day today we stopped to talk to three men on horseback who were looking for a ‘mulato’ (Afro-caribbean man) who was looking for some ‘vacas’ (cows). When we mentioned we were looking for somewhere to spend the night they told us about a hotel that was a few kilometres past the next town. They assured us it was ‘barato’(cheap) and that it had a good restaurant. So on we rode, past another sugar cane town and off route for a few kilometres. Turning down a side road, an overgrown hotel entrance gate appeared, all cracked concrete, weeds and faded paint. A reception building followed, but I’d given up hope, thinking it looked abandoned. But the flicker of a TV screen spied through the curtains was a good sign.

We were then surprised by firstly not being turned away for being extranjeros (foreigners) and secondly by the price: 56 cuban pesos (or roughly NZ$2.89)! Cuba has two currencies: the peso (CUP) and the convertible peso (CUC), the latter being a tourism currency and equating roughly 1:1 with the US dollar, so when we heard 56 – we thought CUC, but no, $2.89 got us a room with a cold shower, three beds, aircon, a TV and a rusty fridge. Perfect! The swimming pool was an additional bonus, along with an equally cheap on-site restaurant.

Most of the restaurants and cafes are state owned, even in the smaller villages, but they’re spartan for choice. Often only having one type of meal available, and even then it’s usually either pizza, spaghetti, rice & pork or stodgy burgers. During the ‘Special Period’ of the early 1990s when Cuba’s economy was at its lowest, out of necessity Castro loosened the rules for private enterprise which was previously totally banned. These days that private business takes the form of horse and cycle taxis, small ‘kioskos’ — where you can buy a juice, a shot of coffee from a flask or a bread roll with cheese or ham — and ‘paladars’ which are small private restaurants. Most often we eat in the state-owned places and kioskos as they’re most common.

Sugar cane juice and a shot of coffee. The coffee’s strong, premixed with sugar and poured from a vacuum flask. It’s hard to find after about 9am in the morning.

Home-fabricated machinery like this is a very common sight – recycled and repurposed parts are used in horse carriages, bike taxis. We even saw homemade lawn mowers. Out of necessity Cubans are incredibly resourceful. I was walking towards a trash can one day with two empty plastic water bottles (the local water was usually untreated, so we sometimes buy it) and a man took them from my hands before I reached the bin. They will probably be filled with fruit juice or rum for sale in a kiosko.

This afternoon we reached Sancti Spiritus, after a long day of mostly following a canal-side track. We ran into more of the acacia and some mudpits on a couple of overgrown sections but on the whole the riding was fast. We sidetracked to one small and very poor village to find food. There were few people around but no-one we asked had anything to sell. Older, unemployed men sat wordlessly under the shade of the few trees. Finally we found a small tienda where an old man had a couple of bottles of rum and a couple of cans on a shelf. He sold us some bread rolls with ham, and then as we headed for an overgrown track back to the canal we found a woman deep frying balls of dough, so we bought a few of those. Hardly an optimal diet for long days on the bike but it seems to keep us going.

Like all of the cities, Sancti Spiritus was abustle with horse and carts and a few cars and trucks. It’s a richly textured place with some cobbled streets, colourful buildings and interesting metal work. So far for us on the cities have become the highlights. Much of the riding is remote, so sometimes we see few people a day and little in the way of much that’s cultural. The cities are alive with the unique pulse of Cuban life, in much the same way as in Havana, and we find the streets fascinating to walk.

We stayed in a casa particular run by an older woman who loved to mumble away to herself while her husband sat just a few inches from the TV watching the boxing. We had a comfortable room and even met a couple of other tourists – the first we’ve talked to in several days.

Some spare bottom bracket axles and crudely cast seatposts in a shop in Sancti Spiritus.

We detoured from the Ruta Mala route to visit Trinidad, Cuba’s most famous and most-visited city outside of Havana. Its cobbled streets and well preserved, colourful, colonial architecture have earned it World Heritage status and it’s a fascinating place. Indeed it’s touristy and the food is overpriced but its a unique place.

The front room of the casa particular we stayed in in Trinidad. Like so many homes in Cuba, it was like stepping into a museum.

This 96 year old man would have it all: from Cuba’s pre-revolution affluence through to economic disaster and everything in between.

We rode through pouring rain between Sancti Spiritus and Trinidad thanks to a big storm that has moved down from the cold of the northern USA. A frigid wind was still blowing as we rode up into the Guamauhaya Range to rejoin the route but this section has turned out to be the most beautiful of the ride so far. Karst outcrops, cliffs, tangled forest cover and the distinctive royal palms make this area special.

We were just nearing El Nicho where we planned to camp for the evening when we met two other cyclists; Rosie and Fiona. Over a coffee from a small restaurant we caught up on each other’s stories. Shorter on time, Rosie and Fiona had started in Camagüey and had run into some of the same trouble we’d had with mud and acacia thorns, except they weren’t both tubeless so they’d had a nightmare with punctures. Then they had a tyre bead separate from a tyre (but with the help of locals got to a town to find a 26 inch replacement). After our own experiences on some muddy, overgrown tracks Hana and I had detoured around a suspicious looking section between San Antonia and La Alina, while the other two said they’d taken all day to battle through 5 km of ‘swamp’.

We’re back on the coast and it’s super beautiful – another highlight of the ride. A long day took us through Cienfuegos, where we stopped for lunch. I ate a burger that left me with a rising nausea for the rest of the afternoon and finally this evening it all came up. But even feeling sick didn’t detract from the specialness of this place. Just before dark Rosie and Fiona arrived at the same spot we have to camp for the night. We’re on a limestone bench – an ancient uplifted reef – that seems to run along much of this section of coast, but at this spot, grass runs over the top of it nearly right to edge and it’s incised with a beautiful small cove of the bluest Caribbean water.

It’s calm and warm, and the cold wind that’s made us wish we had more clothes has finally subsided. We’ve lit the first fire of this trip to keep the mosquitos away.

Today has been a languid cruise along the smooth sandy coastal track. 26 kilometres, not much, but the first distraction was an amazing cenote that just begged to be swum in, although being mostly fresh water it was colder than the sea (which is perfect by the way). The second distraction was a beachside day-resort with a one off entry fee that included all-you-can-eat bufffet and infinite cocktails or beer. A pretty good way to spend the afternoon we thought. It wasn’t busy, the place was beautiful and the snorkelling was amazing: the hugest school of fish I’ve ever seen, and quite a few large fish coming into the cove from deeper waters. After dark we ate left over buffet for dinner with the security guards and then pitched our tents over the road from the entry.

Nearing the Bahia de los Cochinos, site of the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion, we started to see these old gun emplacements along the coastline. Playa Giron has an interesting museum all about the CIA-supported attempted invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles in 1961.

This afternoon we passed through Surgidero de Batabanó, a small coastal town that seemed gripped in a downward spin. Whole rows of houses looked on the brink of falling down, litter sat about the streets and the people were desperate for money. Many of the shops and restaurants we rode past shouted after us – eager to make us a meal and earn a few pesos. We’d already eaten, but we needed water for the remote section coming up, so I asked a couple sitting outside their spartan restaurant. They looked down and out and I felt sorry for them. First they offered a meal, and when I declined that and said I just wanted to buy water, they downgraded to bread and omelette, desperate to sell something, anything, to raise cash.

I followed the man into the kitchen and he took a jug of water from the fridge and filled our bottles. Looking around, it didn’t look as if anything had been cooked in there for months. I couldn’t see any food, just a couple of battered pots and gas burner. I paid them a generous tip and we headed further down the road until we saw a shop that had flan on the menu. Flan’s a common item in Cuba, the most common desert we ever saw and you can buy it very cheaply in some small towns. These flans came in cut off beer cans.

We ended the day, near sunset, in Playa Majana. While we pondered who to ask about camping there a woman approached us to see what we were up to, and after a few moments of chat, invited us back to her house to spend the night. She and her husband had another home in a nearby town, but liked to come and hang out in this tiny fishing village. They cooked us a meal and gave us a bed in return for a few pesos, and we chatted about New Zealand, the long journey we’re on, and the incredibly big mosquitos that seemed to plague the village.

The Ruta Mala ended for us today in the spectacular region of Pinar del Rio at the township of Vinales, a small colonial town turned tourist hotspot. The region is famous for its ‘mogotes’ — great karst towers and massifs that are draped with foliage and beautifully coloured with streaky grey and orange limestone. We pedalled into town in the dark, caught out by a tougher than expected finish of partially overgrown tracks and steeply rolling terrain.

But that’s La Ruta Mala — it’s not called ‘the bad way’ for nothing. The route has thrown surprise after surprise at us, not just in the riding, but in the confusion and challenge of bikepacking the length of a country that plays by a different set of rules. One of the pioneers of the ride, Logan Watts, describes the ride on bikepacking.com as ‘… mentally perplexing and physically demanding …’ and that description could not be more apt.

For us, already seasoned from 17 months of cycling south from Alaska to Panama City (we flew from there to Havana), and well adapted to the biking life it’s been refreshing to be thrown something completely different and we’re leaving Cuba with some indelible memories.

All up we rode about 80% of La Ruta Mala. We were forced off route early by muddy early season conditions (we started late Nov) and then detoured around a collapsed bridge/overgrown section and later a swamp. From Sancti Spiritus we detoured on pavement to go and visit Trinidad but climbed from there back into the mountains to rejoin the route just before El Nicho. Between Jaguey Grande and Nueva Paz we took the highway to make up some time. See the map below. La Ruta Mala in red and our route in blue. The waypoints added are our own notes. For full details refer to the route write up here: bikepacking.com and the feature article by Logan Watts.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Hi there, Yip, you really deserve a beer or two after that! I’ve loved following you guys but this post is especially incredible! I am in awe!

Thanks Jo – you’re awesome. We’re sipping a ‘Club Colombia’ now thanks to you. Cuba was a really amazing experience – a tough ride at times and fascinating to finally see a country I’ve heard so much about over the years. Hopefully some more posts for you soon.

I loved this post! I agree with Jo, this post has been specially intense from the pics to the stories of struggle. I loved the improvised storm shower moment.

At one point I think you mean “Bahía de Cochinos”. And here’s a musical recommendation for you, one of Cuba’s most famous songwriter whom covered the revolution topics. Hope you like it! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkvuru_jPgM

Thanks Mateo – glad you enjoyed! I’ll make the change (oops!)

Fantastic photos and narrative. It’s special to see this route again through different eyes, challenges, and heights.

Joe

Hi Joe – thanks. Yes I’m sure you can appreciate it more than most! Thanks for the trail blazing – it’s a great gift to the community and to Cuba. Ride on.

Outstanding report! Thanks a lot for sharing your epic adventure.

Your struggles of the past are our inspiration for the future!

Hopefully we get to meet you down the road to exchange some stories.

De nada Dennis! Glad you enjoyed it.

Hello Mark,

Fantastic report! I’m very close to taking our tickets for next January to make the same trip.

Question for bike choice: what do you recommend? We have gravel: Kona “Sutra LTD” and Genesis “Croix de Fer”, or 29 ” MTB with a suspension only at the front.

Thank you for your answer,

Hi Jeanne – thank you. Good question re bikes. Basically it comes down to tire size. I think the Bikepacking.com info recommends 2.2? But we were riding 3 inch front and 2.4 rear and would not have wanted less than say 2.4 overall… Some of the riding is quite rough, and it’s consistently bumpy – especially the long distances through flat sugar cane fields (there’s a lot of that). Bigger tires soften the bumps and leave you less tired at the end of the day. A suspension fork is not essential – but again would increase comfort. What size tires will your gravel bikes fit? if they’ll take a big tyre, go for it. Otherwise I’d go the 29er MTBs. Have fun! P.s. tubeless essential.

Thanks for your fast answer! The max for my gravel bike is 2 inch… and less for my boyfriend.

After read your comment, think it’s better to take our MTB. A monstercross will be the best we can’t buy another bike 🙂 and the suspension fork will bring additional comfort indeed!

Hi,

It’s me again!

The departure is coming for this trip (on the same route) in January and I have some questions if you want to answer it.

– Will GPS (Garmin) work in Cuba?

– The tubeless is a problem in the plane?

– Did you take the bus with your bikes between Havana and Santiago de Cuba?

– Need to book Casa Particular?

– Is the food easy to find on the course?

We chose semi-rigid mountain bikes 29 (I think it’s a good choice 🙂 )

Thank you very much,

Good luck on your way,

Your trip is like a dream for us

Xavier & Jeanne