From the Caribbean Coast to Olancho.

Although we’d only just hit the north coast of Honduras, our plan was to ride east through Trujillo and towards the Moskitia region for three days and then boomerang back south west towards Catacamas, Olancho via one of the remotest regions in Honduras: the Paulaya River.

Two sayings are common in Olancho – Honduras’ inland ‘wild east’ state: ‘Easy to enter but hard to leave’ and more ominously ‘Enter if you want, leave if you can’, the latter being a reference to Olancho’s reputation as a partially lawless state. From the first Spanish settlers through to the Honduran government law and order has been an ongoing struggle here and trouble continues today with drug trafficking (which has reportedly diminished) and the region’s oligarchy-led cattle and logging industries which each year take another bite out of the region’s extensive forest. The local people are reputed to be fiercely independent but conversely warm and welcoming, and it was that trait that we hoped would ensure we’d have a safe passage through this state.

Our funnel into Olancho would be via the Paulaya River. Take a look at any relief map of Honduras and a distinctive geographical feature – the Guayape Fault System, a long and complex series of valleys – stands out, slicing the north east of the country between two extensive mountain ranges that both contain national parks; to the west the Sierra Rio Tinto and El Carbon Parque Nacionales and to the east the Reserva Biologica Rio Platano adjacent to Moskitia and comprising part of the remotest region of Central America. This fault system runs (on land) for 290km from the Caribbean down to the southern town of El Paraiso. The Paulaya is the principal river of the region.

Information was scarce: our National Geographic map showed a dotted line representing a track down the length of the valley towards Catacamas, but when compared with Google Maps there were few place names common to both maps and confusingly the roads were in completely different locations. Google Maps indicated discontinuous roads entering the valley system from each end but not joining in the middle, so I turned to satellite maps and RideWithGPS to hand draw a best guess GPX track. It looked like the track was probably continuous but due to forest cover and its narrow footprint it was hard to tell. There was nothing on the Internet to indicate other cyclists had been this way – at least not in the era of the World Wide Web.

I imagined such a back road corridor to the interior of the country might be the perfect drug trafficking route, but locals in La Ceiba seemed to think that activity had dropped off significantly due to US and Honduran government operations. The US ran a covert DEA operation here for some years, only exposed after a DEA agent killed a suspect in the Olancho Region in 2012, but the area’s reputation – and of Honduras in general for violence – has stuck. Still, the locals view we’d be ok gave us the confidence to stick to the plan.

Armed with our GPX track we left La Ceiba with open minds and our fingers firmly crossed.

To head east from La Ceiba, there’s the main highway (inland) or you can connect dirt roads along the coast via a boat ride – we chose the latter, taking the highway as far as Jutiapa and then turning off onto a good dirt road headed for Rio Coco.

For a time along the highway we were shadowed by Doda, putting along on his heavily loaded motorcycle. Doda’s a keen local road cyclist and showed us a few photos on his phone. At the Jutiapa turnoff we parted ways, but not before he bought us a couple of cokes – nice dude!

We’d had a late start from La Ceiba and when heavy rain started just before sunset, camping seemed like a bad idea so we pulled into Rio Esteban, just a few km from Rio Coco, to look for a room. A family ended up renting us a recently finished one-room ‘house’ for the same price as a local hotel after we waited nearly an hour for the hotel owner to show up (they never did). The family even popped out in the rain to get us a plate of fried chicken, salad and beans too. Huge puddles all around the houses in the village suggested that the wet season definitely wasn’t over and we fell asleep (eventually) to the deafening croaks of thousands of frogs that now call the puddles home.

At Rio Coco the gravel petered out into a sandy track and a lonely ‘resort’ stood at the end of the road by the beach. We’ve seen quite a lot of abandoned resorts and restaurants and locals tell us that Honduras was once a a much more popular tourism destination. But sadly the tarnish of a violent reputation is hard to polish off.

We were looking for a local fisherman to take us along the coast to where the Betulia – Trujillo road starts. People in these small villages are always happy to be able to make some extra cash so there was plenty of enthusiasm to help us out.

First of all the canoa had to be coaxed through a shallow creek to the sea (it was low tide). We got in on the effort too.

We motored noisily along the coast, below jungle and palm covered ridges – ranges that looked very similar to the Karamea region of New Zealand. Occasionally we passed a solitary house or hut, usually with a cultivated area on the hill behind it. The canoa was narrow and unstable – at mercy of the swell of the ocean.

Even though we negotiated with a couple of men in the village (we paid $US20) it was a ‘muchacho’ who had to do the work. A muchacho(a) is more or less a teenager, but the term is used widely and can also be used for a slightly older person – such as servant or a cleaner.

After an hour and a half we came to shore on a deserted sandy beach just west of Betulia. The beach was steep and waves broke over the back of the boat as we unloaded our bikes. We paid in Lempiras plus a small propina (tip) for the muchacho. He fired up the engine, turned and headed back leaving us alone on the beach with only the meditative slap of the waves breaking on the sand. We stripped off and jumped straight into the warm velvety sea.

We picked up the small track and headed past a couple of houses. The first people we met were a bunch of very curious school kids.

Then an equally curious white faced monkey, sadly chained up but very hyperactive.

And then a beautiful loro. We’ve come to realise these chattery birds are basically the sparrows of Central America – daily we see big flocks squawking and squeaking as they flap overhead.

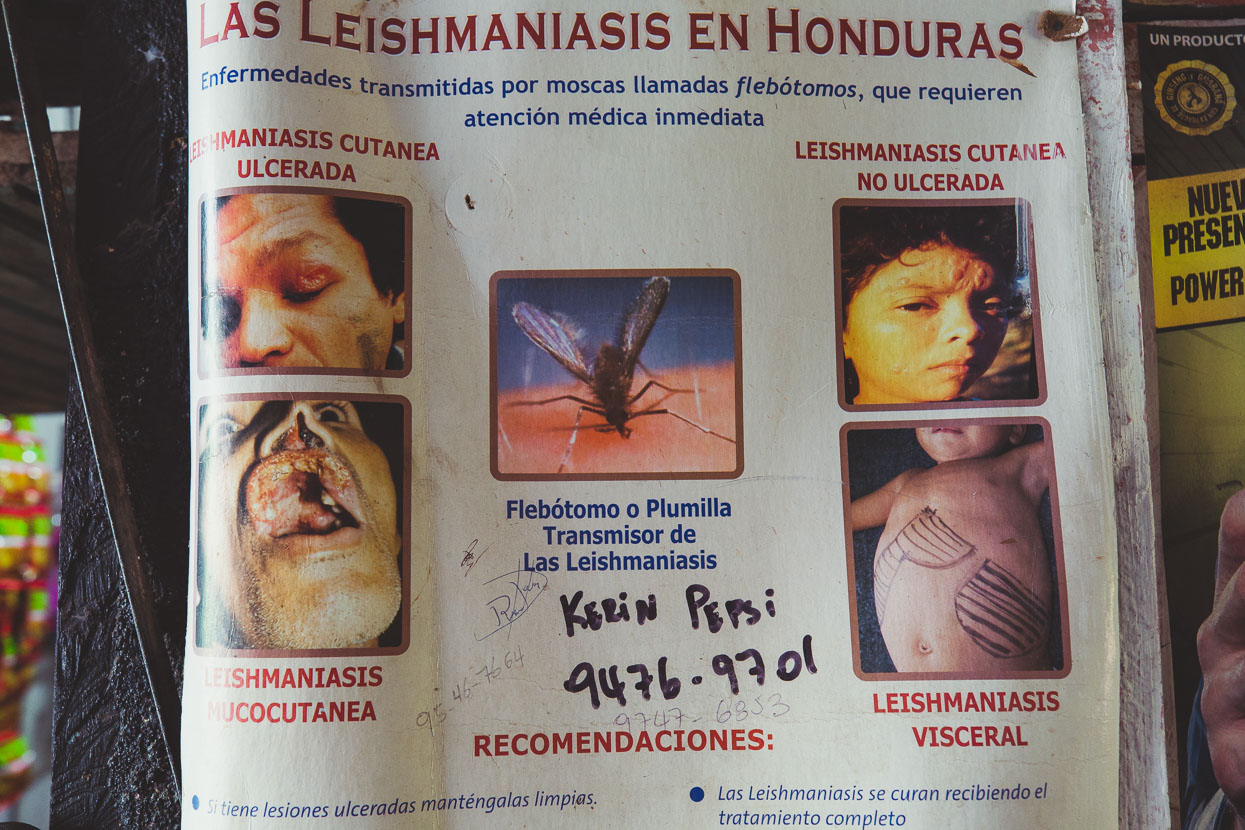

Next came a gruesome warning about the dangers of leishmaniasis – a sandfly borne disease that’s relatively common in this area. As if malaria wasn’t enough!

A bridge took us across to the main coast track and we headed towards Trujillo.

A good quality dirt road led the way past small Garifuna settlements, but we didn’t linger, as historic Trujillo was calling. In Trujillo we stayed at a beachside resort/hotel complex and paid an exorbitant amount for a patch of ant infested grass to pitch our tent on (US$20), but at least it was a safe spot. The German owner – represented by an awesomely narcissistic statue at the entrance that’s actually a remarkable likeness – came to say hello and ask about our plans. Our intentions were met with an arrogant retort:’You’ll never make it – it’s just a giant swamp out there. The whole road will be under water.’ When we said we planned to ride to Punta de Piedra the next day (100-odd km) the reply was a nonsensical ‘No, it’s impossible – it takes three hours in a car’. On the upside, he reckoned the cartel activity was nothing to worry about.

Despite being a bit off the travel radar for most people, Trujillo is one of the most important historic sites in Central America. It’s where, on his fourth voyage, Christopher Columbus – for better or worse – made his first landing on the Central American mainland in August 1502. The conquistadors followed but because of the town’s isolation and small population the area was frequently attacked by pirates. An old fort, the Fortaleza de Santa Bárbara, is the centre point of the town and dates back to the heady 1550s, in the following couple of decades the town was destroyed several times and in the 18th century the Spanish all but abandoned Trujillo, deeming it to be indefensible.

Trujillo has a unique character, lent by its fringe-of-the-jungle location, the Caribbean blue, the mostly Afro-amerindian locals and its scattering of historic buildings. With very little to the east of here it certainly feels like the frontier town it’s described as.

A fine tropical sunrise after a night of rain.

We rode the highway out of Trujillo, down to Bonito Oriental, before turning off onto dirt roads. Sadly the once jungled coastal plain here is now home to forests of African oil palm – where palm oil comes from. This insidious industry has seen the destruction of huge amounts of tropical jungle.

This big limestone cliff was the first cool thing we saw once we turned onto the very quiet dirt road after Bonito Oriental. The road starts off as smooth gravel but gradually deteriorates as you head east, become rutted and rockier.

After 103 kilometres we stopped in Punta Piedra, one of the Garifuna fishing communities along this coast. These communities are unique cultural pockets: established by a people with a complex history. Roughly, the Garifuna are mixed-race descendants of West African, Central African, Island Carib, European, and Arawak people, initiating from African survivors of a slave ship wrecked off a Caribbean island, now living along the Caribbean coast through Honduras, Guatemala and Belize (with a large population in the USA). We’d visited a couple of communities in Belize, but Punta Piedra was different – its remoteness meaning it was well off the Gringo Trail. It was like stepping into another world, immediately we were surrounded by the cultural uniqueness of the Garifuna – a people who are roughly 75% African. Their language, music, culture, style of dress – and immediate warmth – took us out of the Honduras we’d been in and into their world for one night.

The town is without electricity but some households have running water via a small reservoir on the hill above town. No internet, no telephone coverage; the couple of small shops in town selling only the most basic of goods. Almost no-one owns a motor vehicle. Like the town that time forgot.

While everyone smiled and said hello while were guests in their village, the kids were fascinated; following us around on the beach, play fighting, drumming with items combed from the beach and kicking plastic bottles, that sadly litter the beach.

Fishing is the life blood of the Garifuna and that includes eating sea turtles. We saw a few of these huge shells in the sand dunes, sometimes surrounded by hungry vultures.

Jossy and Holson, our hosts for the night. We rented a room in their very basic ‘posada’ and they cooked us a meal of fresh fish, rice and beans for a few dollars. They sat across from us in their small kitchen/store room/lounge and we chatted while we ate, about our trip and their lives. Asking if there were many snakes around the reply was ‘Yes – and when it rains and floods the ground they come inside the homes’!

Somewhere to lay the head.

Many of the houses are simple mud, stick and thatch affairs.

Looking east along the Caribbean coast towards the north east tip of Honduras, from Punta Piedra. We were headed in that direction for a few hours before turning south towards the Sico River.

Cusuna, another Garifuna village just a bit further along the coast.

Turn left for Moskitia, right for the Sico and Paulaya Rivers. In only a couple of hours riding the climate had changed out on the broad expanse of the coastal plain – it was hot, dry and the road was in really good condition.

Typical houses in this area: clearance for flooding, good airflow and plenty of shade to hang your hammock in.

Sambito wasn’t named on the map, but this village had some accommodation and a large (but spartan) general store. Maria Flores (left) owned the store. She was very interested in what we were up to and comprehended the idea of the journey much more clearly than most other people we meet – one question would lead to another and we chatted for quite a while. We asked her about the road condition further ahead to the next big town – Dulce Nombre de Culmi – which was 2-3 days ride away (it was good smooth gravel at that point) and she gave the same answer we’d had from a couple of hombres earlier in the day: ‘Es lo mismo’ (It’s the same).

The Sico River’s unbridged but served by a large ‘balsa’ to cross the river. Basically a floating jetty with a couple of outboard motors. The town on the other side of the river has a small comedor where we got a comida tipica lunch for about NZ$3 – chicken, yucca, rice and salad. There were a few houses, a small military camp and a hotelito (which is actually marked on Google Maps!).

The road onwards alongside the Paulaya River was good quality, if not a bit flooded in places. The valley seemed to have a climate of its own after we left the parched coastal plain – a lushness and verdancy you only see in a place that’s nearing the end of the wet season. Either side of the road cattle (the main industry here) grazed among remnants of forest and the mountains flanking the broad valley were lost in the cloud and mist.

If the standard of the bridges are a measure of road quality, things were starting to get a bit more basic…

Some of you might be familiar with the book ‘Lost City of the Monkey God’, by journalist Douglas Preston. This story delves deep into the very recent confirmation, by advanced radar techniques, of a ‘lost city’ sometimes referred to as La Ciudad Blanca deep in the extensive rainforest just east of our route. Earlier explorers had reported the evidence of ruins in this area, but recently a joint Honduran/USA expedition ventured into the jungle clad mountains and discovered more about the true extensiveness of this unique pre Columbian civilisation that paralleled the Maya, however there is more still unknown than known about the history of this discovery.

What is known is that we were riding on the edge of a giant rainforest reserve area that’s falling under increased pressure from cattle farmers and loggers who continue to impinge on the forest and the traditional ways of life of the indigenous people.

We spent the night in Copen, the second of the two farming villages after Sico. We weren’t confident about camping in this area and with rain all afternoon and continuing into the night we were keen for some shelter. A half finished hotel provided for that – with a basic room with a single bed (and a mattress on the floor) but the water wasn’t connected yet so it was back to the bucket showers we’re more familiar with anyhow. A single comedor in the village served only baleadas, which are basically a breakfast burrito without the bacon and probably our best food discovery in Honduras.

Crossing a stream with a couple of cowboys the next morning. Like most of the men we saw in this valley, these two guys wore pistols on their waists, confirming the vigilante law that seems to prevail in this area – we hadn’t seen a policeman for a while, and the only military were in Sico.

Looking west across the valley towards the Parque Nacional Sierra Rio Tinto. Rio Tinto is another name for the Sico River.

About 4 kilometres past Copen the formerly reasonable gravel road turned into a muddy track – so much for Es lo mismo! At first we weren’t even sure if it was the road and turned back after a few hundred metres to ask a couple of hungover looking farmhands at a wooden shack just off the road – but it indeed was the route to Olancho. No longer were we headed to any particular town – everyone just referred to whatever was ahead as simply Olancho, like it was this distant ‘other’ place that they’d never go to because it was too hard – and that’s a bit how it was…

The bridges were definitely getting worse…

Not a bad place to be pushing your bike though!

The road was more or less a rough 4WD track, but probably only navigable by vehicles in the dry season. We only saw motorcycle tracks.

Lots of water crossings, some quite a lot deeper than this, and plenty of water-filled muddy ruts. But in the dry season travel would be much easier.

We occasionally saw ranch workers on horseback – the horses definitely looking more at home on the greasy track than we were.

Taking a break at the confluence between a side stream and the Paulaya River. I remember splashing handfuls of water on my face and head here in an effort to cool off and wash off the sweat. I think it was at this point that I compared the ride to the Baja Divide: ‘Not always super great riding and feels slightly masochistic, but it takes you through some interesting and unique places’.

I don’t recall the name of this hamlet but it was a tiny place with a single small shop (the first since Copen). Several horses were tied up outside the church, where the hamlet’s inhabitants were being subjected to a loud and energetic sermon that never seemed to end. We bought some cokes and little bags of chips and sat in silence outside the shop while some surly teenagers and a girl who looked way too young to have her own baby stared at us.

We passed a ramshackle homestead on the other side of the Paulaya and had started pushing our bikes up another hill to the sound of Whitney Houston coming from the house when we heard voices shouting to us. Over at the homestead some people waved and then a person on horseback began to cross the river. A girl dressed completely in pink rode up to us and introduced herself as Briana. Just 11 years old she lived here with her family, who’d moved back to this incredibly isolated place to run their ranch after living in the USA for some years. Eventually dad rode over the river too with two of the sons. They were off to watch a football game in a small village a couple of kilometres away.

We pressed on, wading and carrying the bikes across the Paulaya River four times past a couple of tiny villages (at least one had a small shop) before climbing steeply onto a ridge. The riding got really good here – a rough but fast road that was a bit drier away from the river and had some nice views of the surrounding hills.

Night falls quickly this close to the Equator and darkness was almost upon us when we came over the top of the hill just above Rio Frio, a small village scattered about steep hills. We pulled up outside a tiny hut (left of centre in photo) that turned out to be the only tienda/comedor and said we were looking for somewhere to sleep. Within a minute we had an offer from the woman who ran the shop and the farmhouse over the road, not only that but when we asked about food, she presented up some pork, beans and rice and wanted nothing in return.

We sat and ate in the dark outside the shop while inquisitive locals came to check us out, sometimes just standing in the shadows staring, but pretending they weren’t when we looked their way. One more confident young guy asked us a lot of questions and on the whole our first Olancho village was very friendly.

When I say farmhouse, it was really that: a small compound where the human inhabitants had some rooms, and a multitude of animals including pigs, chickens, ducks and dogs slept under the walled eaves. The pigs were on one side and we were on the other in our tent, but come dawn it was a free for all as feeding time neared. While we pitched our tent Marta, the owner who’d cooked us the meal and her young son, watched fascinated as we unpacked and made our simple beds for the night.

We left early, with about 45km remaining to get to the town of Dulce Nombre de Culmi. We were feeling exhausted from the previous day and struggled up the hills.

But finally, at the village of Las Marias, the road improved and then we reached a bridge – the wading was over, and an improved road led us onwards. With the change of road came a change of ecology and climate too and now the smoothly rolling hills were covered with pine forest.

Dulce Nombre de Culmi is a centre for the local indigenous population; the Pech, but their culture wasn’t evident in the same way as indigenous peoples we’d seen in Guatemala or Mexico. More, the town felt like a farming centre that hadn’t quite rolled over into modern times. Internet and mobile phones seemed to be a ‘new’ thing.

But it turned out that Marta – our host from the night before – had come into town too that day, on the back of a pickup for one of her occasional resupplies. It was funny to see her dressed up in townie clothes, with her mobile phone, after the peasant-like conditions we’d spent the night in. We were happy to return the favour by buying her lunch and she even dropped by our room again in the evening to chat more – good Spanish practise for us.

In the morning I slipped on some steel stairs that were wet from overnight rain and fell heavily on my back, cutting open my elbow on the corner of one of the steps. It was a deep cut that bled like crazy and I was worried there might be dirt from the step inside so it was off to the medical clinic for some stitches.

With my elbow patched up we hit the road, finally saying (temporarily) goodbye to the dirt roads about 30 kilometres from Catacamas. By now the valley had really opened up into farming country again and the riding was a mostly downhill spin to the city.

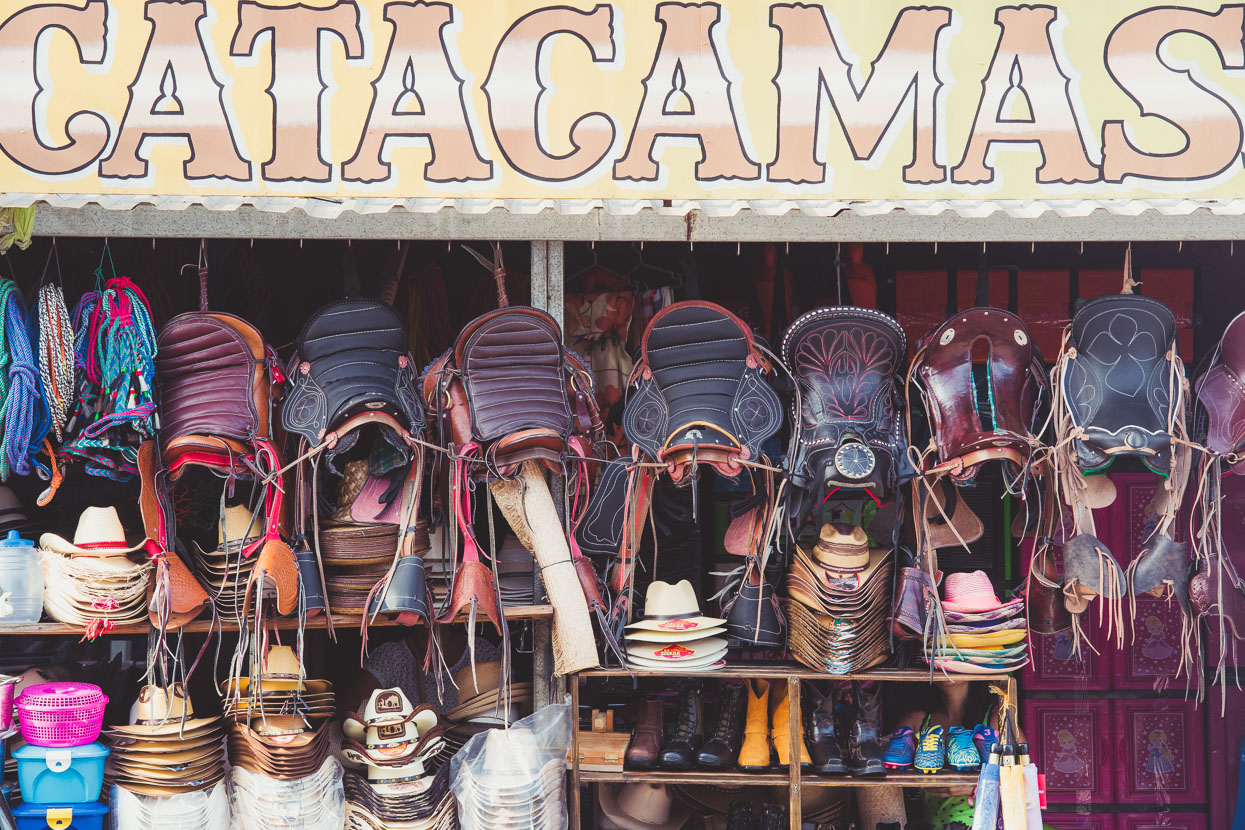

Catacamas too was a farming town through and through. There’s a very small tourism industry with the nearby Talgua Caves, which we didn’t visit, but we did take a much needed rest day after over 400 kilometres of mostly dirt from La Ceiba – a route that challenged us and that we are very happy we persevered with. We’d seen a remote corner of Honduras – a country that fascinates us more and more – experienced the kindness of strangers and made it into Olancho. Now we just had to get out again.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Fantastic adventures! Great post, we’re still reading :-). All the best.

Thanks Anna!

Where are

You heading next? Good

Stuff! Thanks

Thanks Bill! Since that post we’ve completed the rest of CA down to Panama City. Flying to Cuba tomorrow for three weeks riding and then onto Columbia! Looking forward to seeing more 🙂

Mark & Hana.

Love it Mark! Anja says you guys are absolute legends! Kristen

Thanks Krispy and Anja! hope you guys have a great Christmas 🙂 We miss NZ a bit 😉 ??

Hi Mark & Hana,

what a fantastic adventure! I lived in Honduras in 2000/ 2001 for a year and travelled around the country every weekend – that was all pre-Digital Cameras. It’s so fantastic to follow your adventure and read about Honduras, and also an area I haven’t been yet. Makes me want to go there again – also by bike like you two!

Enjoy Cuba, Panama and Columbia, and I’m sure to follow along!

Thanks Hendrik and thanks so much for the donation 🙂 Enjoying a beer right now at the end of the Cuba Ruta Mala bikepacking ride! Columbia next…