Back to Guatemala.

My last post reported that we’d arrived in the cruisy seaside Garifuna village of Hopkins – on Belize’s Caribbean coast – only to discover a broken axle on my rear wheel just a few kilometres into our departure.

After a 12 day wait we finally got the parts we needed to get back underway. While the hold up was a definite inconvenience, we were lucky it happened where it did – Hopkins was a really pleasant place to be stuck. We hung out at a gringo-owned backpackers (run by the excellent hosts Anna and Roy, below). Our days started with a swim in the ever-choppy but blissfully warm Caribbean and with good internet I was able to get a bit of work done most days. The Tour de France had started, so we downloaded stages daily and my 46th birthday came and went, celebrated with the local rum.

Belize has relatively few roads, so highway it was – albeit a quiet one – headed south once we got on the road again. On the way we rescued a turtle from a possible flattening on the highway – a fate that had befallen a couple of his mates. The cute fellow retracted all his limbs when we picked him up and then seemed to relax when he realised we probably weren’t predators.

Our route through the rest of Belize back towards Guatemala took us through the town of Placencia – a resorty location on the tip of a long and very skinny peninsula (just a couple minutes walk across in places). We spent a night there and then caught a water taxi across to the mainland, where we resumed an easy haul down the gently rolling highway towards Punta Gorda.

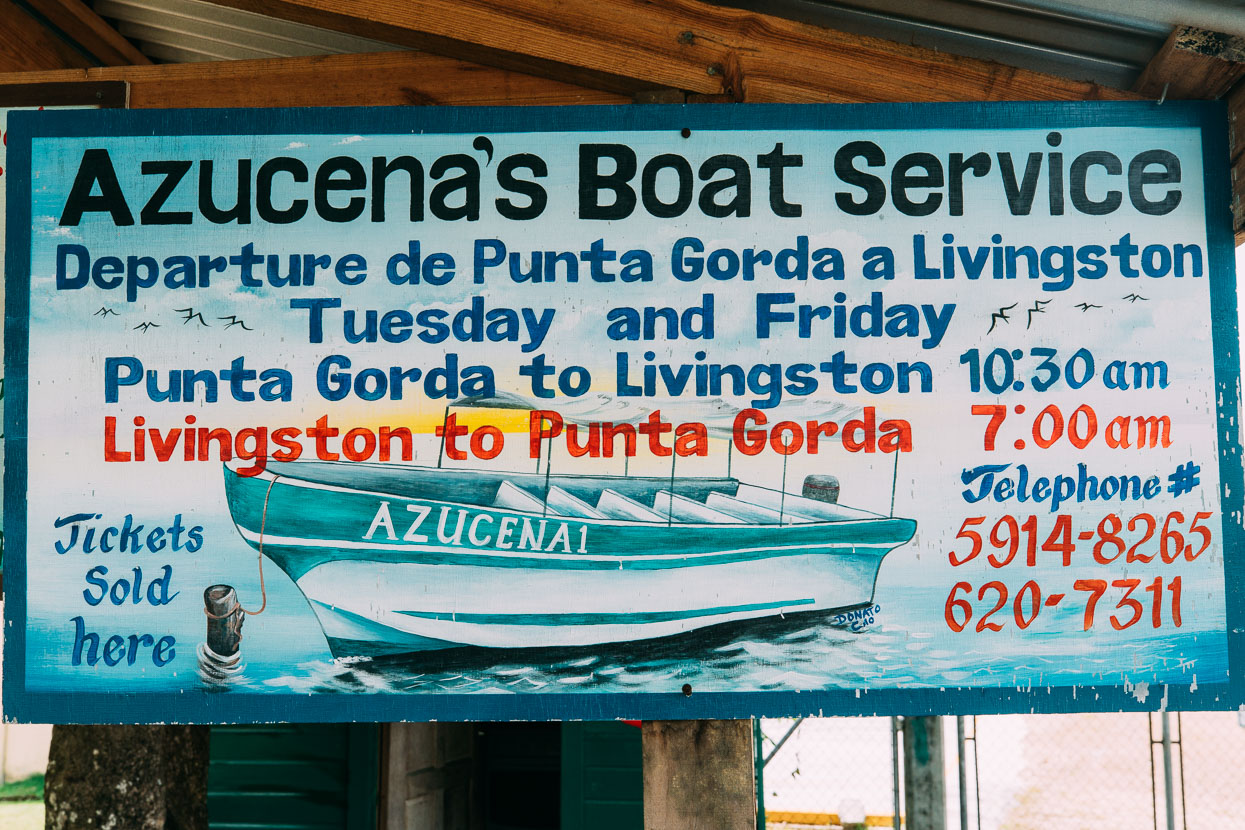

Punta Gorda was another Garifuna seaside town. A scruffy place of weather battered buildings and peeling paint that reminded me a little of some of New Zealand’s coastal suburbs. For us it was an essential stop as it’s the only immigration office in Southern Belize and is the point of exit/entry for people making the classic Belize–Guatemala circuit towards Livingston, GT, which is only accessible by boat. From there people bump again on a boat through the Rio Dulce Gorge to Rio Dulce township.

Alongside the unlikely mix of Maya, mennonite and Afro-amerindian, East Indians comprise one of the bigger ethnic groups in Belize. Charles, the elderly owner of the hotel we stayed in there chatted to us for quite a while in the morning. Born to a Guatemalan mother from Antigua and a East Indian father from Honduras, he’d run a telecommunications business and held various public offices in Belize. He proudly told us about meeting the Queen.

We signed out of Belize at the immigration office and hopped in a small fibreglass boat with a few other tourists and locals. Destination Livingston, Guatemala about 45 minutes away.

Our first glimpse of Livingston is the ramshackle port and a few buildings poking out of the trees. This isolated settlement occupies a small tip of land on Guatemala’s tiny section of Caribbean coast, just a very short boat trip from both Belize and Honduras. Despite the ebb and flow of the tourist boats, this place has an exotic ambience and a sense of slightly shambolic mystique surrounds it – a kind of Wild West on the Caribbean. Thick jungle spills down mountainsides right to the water’s edge and the developed world feels much further away than the hour long boat ride that it is.

We had no problems getting stamped back into Guatemala for another three months and then rode off to find a basic room at the Casa De La Iguana.

While the coastal settlements Gales Point and Hopkins back in Belize had been almost purely Garifuna, Livingston is notable for being a mix of both Garifuna and Maya and the two cultures seem to sit side by side quite happily in isolation here, the streets ababble with the sounds of Mayan, afro-amerindian languages, Spanish and English.

Smoke clears from a big string of fireworks thrown into the middle of the street early in the morning. Random explosions have formed part of the background score of much of our ride through southern Mexico and Guatemala. The noise of fireworks is believed to scare away evil spirits and forms a big part of fiestas, especially those surrounding religious ceremonies.

While the location is magical, the town of Livingston itself didn’t inspire us much. The main road is fringed with over priced restaurants and touristy knicknacks and I couldn’t help but feel we were 20 years too late to sense this place’s true Caribbean buzz. I preferred to wander along the grungier road adjacent to the shoreline, but even there points of real interest were few.

After a single night in Livingston we were on a boat again, this time headed briefly inland through the incredible natural feature of the Rio Dulce Gorge through which the rio flows to the sea from El Golfete, which in turn is fed by Lago de Izabal, Guatemala’s largest lake.

Here the river has cloven a passage through limestone walls hundreds of metres high, all ensconced in thick jungle, cascading vines and palm trees. It was an amazing sight, even from our fast moving water taxi, which had been promoted as a ‘tour’.

It was enough though to catch sight of a couple of the small Maya communities that live a semi aquatic life along the river’s edge, paddling their simple cayucos. Further upstream these humble existences are contrasted by the river-retreats of Guatemala’s wealthy.

The terminus of our river ride was Rio Dulce, a small township concentrated around both ends of the monolithic highway bridge that spans the river here. Such a construction could not be more incongruous in a landscape consisting of low lying mangroves and river channels. It reminded us a lot of the Mekong Delta.

A last sunbathe before we hit the hills again and make the long upland ride to the highlands.

We hit the pedals the next morning, following mostly good paved roads paralleling Lago de Izabal towards El Estor. It was so good to back back in familiar territory: the tourist restaurants were gone, replaced with thatch huts and kids running naked among chickens. Back is the ‘Hola amigo!’ and a wave. It feels right.

Just before El Estor we stopped off at El Boqueron – an impressive canyon formed where the Rio Sauce issues from the limestone massif of the Sierra de Santa Cruz – a perfect spot for a cool off.

Guatemalans are experts at repurposing potential waste – the picnic tables at El Boqueron consisted entirely of car tyres and the supports for the shelters were made from concrete filled drink cans. We’ve seen whole fences made from plastic bottles.

Getting away from the tourist towns means cheap eats again too. Here’s a $2 lunch. I love the pre cut fruit too.

Many of the villages along the shores of Lago de Izabal aren’t serviced by road, so El Estor is a hub for market supplies and other town essentials. There was a constant buzz at the wharf as lanchas filled with people returning from the shops and market to their distant villages.

The classic ‘single lane’ of pavement on a half finished road that inevitably gets used as a two way lane.

Finally we turned away from the Polochic Valley on a dirt road (highway 29) and began climbing into the sierra. After the mostly flat riding of Belize this came as a small shock – especially once the road steepened. We weren’t yet high enough to be away from the stifling humidity of the lowlands either. Interestingly this road does not even appear on Open Street Maps, except in small fragments.

Into the fresh air and amazing landscapes of Guatemala’s karst mountains.

After a solid couple of hours of granny gear climbing we started thinking about somewhere to stop for the night. Fresh water was plentiful, trickling from abundant springs and so were small villages and dwellings scattered along the steep hillsides. In Seococ Chulac a young man shouted after us as we rode past to ask where we were going, and why so late in the day. Our answer was Buscamos para lugar a campar o domir (we’re looking for a place to camp or sleep), which was quickly followed by an offer to sleep right there. We said yes.

Even as the conversation transpired a small crowd was gathering, but by the time we rolled our bikes to the wooden hut we’d been offered, half of the village’s kids were in attendance to witness the strange gringos, who they normally only glimpse going past in buses.

A local snack – deep fried breadfruit with condiments. For 1 quetzal they were very popular with the kids.

Things got even more interesting when we went to pitch our tent inner (to keep the bugs off) in the dirt-floored hut. With absolute fascination the villagers watched every action as we pitched it and inflated our mats. After the excitement died down we sat and ate some food in the room while one of the girls stood stroking Hana’s blonde hair.

The home of Rojelio Choc and his wife and extended family (as far as we could figure grandparents, parents, kids and grandchildren all under the same roof). We were included in the family breakfast before we hit the road, a couple of fresh, warm tortillas with a dollop of tasty homemade salsa.

Great to be back in the folded and forested landscape again.

A short stop for lunch in Cahabon before we dropped away from the ‘highway’ and followed an even smaller dirt road alongside the Rio Cahabon. After a steady morning of steep climbing we were finally experiencing the much feared percentages of Guatemalan roads. Throw a slippery limestone surface into the mix and it can make for some really hard riding. Our route along the river had lots of short sharp rollers but very little in the way of traffic.

We’d climbed a bit over 2000 metres vertical that day already when not far from Lanquin Hana suddenly hit the wall, which is unusual for her. It wasn’t just a lack of food of water unfortunately and within seconds of checking into a room in Lanquin she began throwing up.

Lanquin’s a pleasant small town perched on the edge of a lush valley: a crazy and convoluted landscape of limestone canyons, caves, resurgences and intricate topography. The town is the hopping off point for the famous aqua-coloured pools of Semuc Champey, just 10 kilometres away. Once a quiet backwater (it still is really), these days Lanquin is abuzz with tourists coming to see one of the most talked about attractions of the Gringo Trail. No longer an obscure and hard to reach location, Lanquin has equipped itself with several hotels and large ‘backpacker barns’, mostly in really nice spots alongside the river, while the town had managed to hang onto its Maya vibe.

This young boy was walking though the village in gum boots several sizes too big, carrying a heavy looking lump of wood on his back with a head strap. He returned my initial glance furtively, but when I smiled and said hello his face relaxed into a big smile and he kept looking across at me as we walked side by side. A couple of moments later I asked to take his photo, and gave him a quetzal for his trouble.

The next morning we tackled the brutally steep road over to Semuc Champey. Hana was fully in the grip of a stomach bug by this stage, and despite a plucky effort didn’t last long on the road’s unforgiving pitches and decided to catch a ride in a passing pickup, while I soldiered on.

At the top of one such power test, I stopped to practise my Spanish with these two guys who’d blown a head gasket on their truck and had the engine in parts. The ability of heavy vehicle owners here to self repair amazes me. A five hour job to get this one done they reckoned.

Over the saddle the road plunges down in equally steep pitches to the Rio Cahabon…

…and across a sketchy old bridge. An ambulance had passed over it moments before I did.

Looking down on the famous pools from the mirador.

The pools sit on a 300 metre long natural bridge that has somehow formed above the main river (possibly the remnant of a cave ceiling?), and are fed by small stream. There’s an incredible tranquility to them as the water slowly cascades from pool to pool, gradually descending the natural bridge. This calm is contrasted by the raw energy of the Cahabon River which cascades through bouldery cataracts and then vanishes into silence beneath the bridge.

The top of the limestone bridge where the Cahabon rushes beneath.

At the bottom end of the pools the water cascades over the edge to meet the Cahabon as it remerges.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Your pedalling into the hills of Guatemala looks fantastic! The real McCoy. Really enjoyed your pics up in the wee village over night. Takes us back a while.

Beautiful tropical locales so much contrasting with our present of frozen trips on skis. Look after those bikes and your stomachs…

Thanks Neil! Yes so great to get away from the more touristy Belize and back into the wild and random 🙂

Fantastic to see your pedalling up into the hills of Guatemala. Loved the pics of the overnight in the wee village. You are in some beautiful country. So tropical cf our frozen ski trips lately. Look after those bikes and your stomachs…

Enjoyed this – nice work!

Thanks Gaye!

Wow… beautiful pictures & interactions with people.

Thanks Stephen – yes we’re loving it. The people we meet make the journey.

I have really enjoyed following your blog and instagram feed. Your photos are spectacular!

I’ve been planning a bikepack tour though Belize and eastern Guatemala. I’ve heard from a couple people that Belize is a dangerous place to travel through.

Did you ever feel unsafe or have fears of being assaulted/robbed during your travels in rural Belize?

Thanks.

Thanks Paulo. We have had nothing close to trouble in Guatemala or Belize – everybody has been friendly. However, Belize City definitely felt like a place you wouldn’t want to wander around at night. The rest of Belize was fine. But the usual precautions apply … Take care at night (as you would anywhere).

Hi Mark & Hana – doing a bit of catch up, your blogs continue to inform & inspire – the pic of Hana on the ‘brutally steep road’ has that zig-zag look about it and reminds me of some of hills I encountered on north coast of Sulawesi back in May (and south of Padang getting to Ngari Sungai Pinang/Ricky’s Beach House in 2015) A test of character & bike handling at s l o w speeds …..