La Montaña, Guerrero.

We’d reached Malinalco tired, but super satisfied with the previous days of riding and our excursion over the top of Volcan de Toluca. Seeking the path less travelled through Mexico had been working for us well and we wanted to keep the theme going as we continued south east towards Oaxaca.

Over a long session at the laptop in Malinalco we plotted a route of 676 kilometres through the La Montaña region of Guerrero State and into Oaxaca state. The elevation stats that Google Earth threw back at us were sobering: 15,000 metres of climbing over what we estimated would be 11 riding days, or 1400 metres of climbing/day on average. La Montaña is part of the Sierra Madre del Sur and is one of Mexico’s most consistently mountainous regions. It’s also one of the poorest, described by Wikipedia as ‘one of the most marginalised areas of extreme poverty in Mexico’.

A review of some of the pueblos we’d pass through consistently revealed some interesting stats: 98% indigenous populations, 25% illiteracy, 0% private internet. 80% of people speak an indigenous language, and up to 50% speak an indigenous language but not Spanish.

It wasn’t without some uncertainty that we set off into this remote region of Mexico. The map showed plenty of villages, so we weren’t concerned with water and resupply, more that we might be unwelcome stepping on someone else’s turf.

From Malinalco the landscape continued to roll away in a downhill direction – slowly dropping us from 1800 metres down to 1000 within 100 kilometres. As we went down, the temperature went up – a lot! What had generally been hot days and cool nights the previous few weeks became very hot days (30-35°c) and muggy nights.

The mountains around this region are principally limestone karst. Our first stop – after a relatively short day mostly on pavement from Malinalco – was Grutas de Cacahuamilpa National Park. The area is famous for caves, rafting and hiking and the idea of going underground on such a hot afternoon sounded good.

A small fee gains you a guided tour of a very large and extensive cave near the park entrance. The walk into the cave is two kilometres one way, and you’re free to walk back out at your own pace.

We explored a little by ourselves too, hiking further into the same canyon to check out two other impressive cave entrances near where the rafting operation is run from. The park allows camping in the swimming pool area (all part of the same park operations area) and it’s a safe and comfortable spot for the night.

Our Google My Maps ‘walking route’ delivered us some interesting deviations to keep us away from the highway. Much of the time on day two we rode alongside and through small farmlets – following a mixture of pavement, dirt, and unlikely looking access trails along the edge of paddocks. Now and then popping out into pueblitos that weren’t even on our map.

This family was refilling their water tank from a streambed well and were amazed to see us there. Many questions followed, most of which we could manage an answer to.

After a climb over a pass made brutal by the heat we followed a long section of pavement out to Coaxitlan near highway 95D (the route to Acapulco). We asked around Coaxitlan for somewhere to sleep for the night but didn’t turn up any offers so we made a short detour to some basic rooms and a pollo al carbon dinner at the highway.

We rode the highway for about 10 kilometres in the morning and then turned off to the south, following deserted double track through sun baked hill country over a couple of passes. No vehicles and no people except for one isolated village. A very nice ride.

After San Miguel de las Palmas we hit a hilly paved road and were on this the rest of the day through to the very remote Papalutla Guerrero, way down at 600 metres on the Atoyac River. Notable for being the lowest we’d been since leaving Mazatlan and the only decent sized river we’d seen in Mexico!

Small ranchitas seem to survive on very little out here.

For a day where we dropped to only 600 metres elevation, there was still 1600 metres of climbing.

After a long, hot day the pools just outside of Papalutla were an oasis indeed. We arrived just before dark but managed to get an order of quesadillas con pollo in just before the cocina closed up for the night. They had rooms for 200 pesos too (around NZ$14) which saved us pitching the tent and gave us more time cooling off in the pool.

The burro is the utility truck of rural Mexico.

We rose early and headed into Papalutla itself not long after sunrise. We had a very big day of climbing ahead of us: from 600 metres to a highpoint of 1800 metres, totalling 2405 metres by the time we reached Olinala at the end of the day.

We left the cactus and the Atoyac River behind and began riding up, up, up on a very quiet paved road.

We asked at a small tienda (the only one we would see all day) in Xixila for some boiled eggs, and they obliged – bringing us some queso and tortillas to turn the humble eggs into a meal. The couple wanted only 8 pesos (60 cents) for their trouble and refused extra money when we tried to offer it.

We also asked if they’d ever seen other cyclists along this road ‘has visto a otros ciclistas aquí’ – a question that was met with a definite ‘no’. We’d receive the same answer the rest of the way to Oaxaca.

Hills like the face of a sun beaten old man.

In an area where timber is scarce, mud brick is the budget building material of choice.

Olinala’s ‘church on a hill’.

Jaded from both the climbing and the heat we took a day off in Olinala to rest, before the next haul through the mountains.

This rubbish bin made from repurposed soft drink bottles caught my attention once we were back in the hills the next day.

The climb out of Olinala took us into an even remoter area where most of the people were indigenous. The standard of the roads and quality of some of the housing fit with the descriptions we’d read. We turned off a poor quality paved road onto a dirt track on a long ridge which we followed down through several pueblos.

We turned heads in Coachimalco. One young man approached and asked us why we were there, before going on to say that we were the first gringos to ever visit.

‘Thank you for coming to my village’ he said before shaking our hands and leaving.

Another trio of boys gathered and asked questions, before a slightly older man, Franciso, approached to chat. He’d been to the USA to work and knew a bit of English. We followed him a short distance to his shop where he gave us both cold drinks and chips and wouldn’t let us pay for them.

Franciso and his tienda (shop).

We frequently see huge stacks of corn stalks (we think?) drying in the trees or on elevated wooden platforms.

We passed another small pueblo along the ridge and then dropped down a long and windy descent towards a big valley containing the city of Tlapa de Comonfort.

We weren’t sorry to be leaving the barren and hot valley of Tlapa behind the following morning, but we had failed to closely inspect our Google My Maps route. The GPX track led us smoothly into a quiet valley at first, but as we gained height it turned into a narrow arroyo and then just goat tracks out the sides of the canyon. We could see the road we needed above us, so on we pushed.

The most barren and hottest part of Mexico yet (outside of Baja). The forest cover no-doubt lost many many generations ago.

More hot and hilly riding followed as we headed deeper into the mountains. At first on baking hot pavement through one of the most arid valleys I’ve ever seen, and then on a narrow dirt road after we got high enough to reach the pine forest. The elevation gain was hard work, but we were thankful of it for the cooler temps.

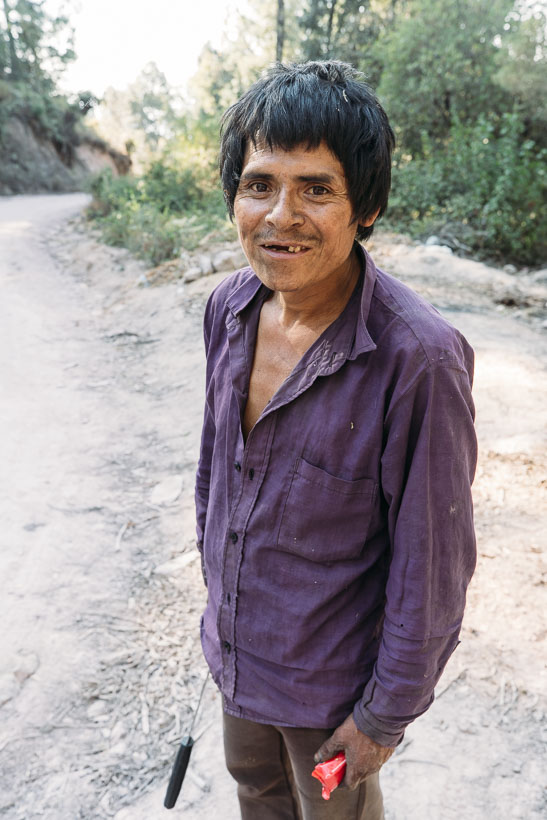

Evaristo (below) wandered out of the forest as we were fighting our way up the steep dusty road. A simple greeting broke the ice and this man was all smiles and quite interested in what we were up to. He spoke Spanish, thickly accented with an indigenous language. I asked to take his photo and gave him a granola bar in return.

Here’s a description of the day written for a Facebook post:

The air was filled with the smell of raw sewage, but we sat outside the small store drinking juice and eating snacks. You become accustomed to the smells of rural Mexico after a while.

A man stopped and asked us the usual flurry of questions: Where are you going? From where?

San Vincente Zoyatlan, we say. It’s still 40 kilometres and over 1500 metres of elevation gain away.

‘Oh, muy peligroso’ (dangerous)! He says.

The man makes a pistol with his hand and points it in the air – miming a trigger pull. He looks serious.

‘Many guns there’. He says, his face narrowing.

We ride on in doubt. Uncertain we are doing the right thing riding into remote, 98% indigenous Guerrero. Riding where no gringo has ridden before.

It’s a long, hot, dusty afternoon. Near dusk we stand on the edge of a dirt road overlooking Zoyatlan. At 2000 metres the air is cooler and the temperature much more pleasant. The last of the sun touches the town’s church as shadows fall across the valley.

We ride into town to stares, smiles and ‘buenas tardes’ from half a dozen people. Half clad kids run dirty on the road. Dogs fight. Pigs grunt and grovel in the gutters.

In the centre we stop. Tired. Thirsty. Covered in dust. Children and women gather in small groups and gaze at us.

We approach a group of men and ask if there is some place safe to sleep, that we don’t need a bed.

They’re immediately helpful. One leads us to a run down Municipal building to meet the commissario (head of the town council) and asks him for us. He too is helpful – immediately understanding of our situation.

‘Yes’, the answer comes – but the men return to a meeting. We have to wait.

Food is priority #2. A small stall nearby sells tacos. We sit and eat with a curious and friendly family running the stall. They smile and chatter in a language unknown to us, occasionally turning to Spanish.

The village head leads us to a small classroom – our home for the night. We sleep in peace. There are no gunshots – just bells, dogs and roosters.

Thank you San Vincente Zoyatlan.

Fidel was one of Zoyatlan’s seniors and was keen to chat to us and show us a view of town from the roof of the Municipal building. We asked him if he had seen any other ciclistas. An emphatic ‘no’ was the response.

‘Ustedes son los primeros’.

Los Primeros. We liked that.

The most colourful moth we have seen so far.

Pushing on the next day through more polvo – inches-think dust over the top of the road. It squeaks almost like snow when you walk on it and is sometimes nearly as slippery as powder snow over ice.

After Zoyatlan the villages got even poorer and the people more shy. Trucks would pass with folk on board who would just stare expressionlessly and ‘hellos’ were timidly returned, if at all. The road remained dirt until Coicoyan de las Flores where we stopped for lunch. We were just inside Oaxaca now.

Embarazada = pregnant.

Streets of Coicoyan de las Flores.

Church and municipal building in San Martin Duraznos. Despite the poor utilities and poverty in these small villages these buildings always hold pride of place in the community and are generally well maintained – especially the church.

Arriving in the small highway town of Santiago Juxtlahuaca was a treat after the thick dust of the back roads and the variable reactions we’d had from local people en-route. A bustling taco stand made dinner easy and the hotel shower felt so good.

The hotel staff were friendly too – photographing us before we left town and even recording a short video for their local tourism page. The remaining ride to Oaxaca will follow in the next post…

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Looks perfect! Thanks again for sharing.

Mike