Within a few hours of leaving the shady alpine valley of Platoro we had crossed into New Mexico – the last state traversed in our journey along the Continental Divide of the USA.

As we pedalled into this new state we said goodbye to the Rocky Mountains which had defined so much of the ride and entered a region of smaller but ever changing ranges. Through southern Colorado place names had been becoming increasingly Spanish, and as we pedalled further into the state Hispanic cultural influence became almost omnipresent. This, combined with an amazing geology made New Mexico the most diverse state we’d ridden through.

Heading down valley following the Conejos River from Platoro; gentle autumn sun and a fresh tail wind made it a nice ride.

The valley’s population is small and concentrated in just three small, seasonal communities. A large herd of horses shadowed us down valley for a while, before crossing the river and heading into the trees.

Morning tea time at the highway before the grind over La Manga Pass.

Conejos River Valley and the South San Juan Wilderness from La Manga Pass. We’re still in Colorado, just.

The pavement undulated away from La Manga Pass and an unabating wind threatened at times to blow us off our bikes. But soon we were on dirt again and in the relative shelter of a gentle valley as we climbed gradually into Carson National Forest, and New Mexico.

Steep and winding two track led us through pockets of forest and out onto the windy tops of the Osier Mesa where a lone teepee made from branches stood. It’s a great swathe of exposed high country and the wind chill was definitely into the negatives. We sped down the loamy tracks and into an open basin on the edge of Brazos Ridge, seeking a wind sheltered camping site among the trees.

High winds tugged at the grass and rushed through the trees.

A copse of trees and some nearly flat ground made a comfortable site for the night. We’d planned to camp on the crown of Brazo’s Ridge for sunrise views but the freezing wind put an end to that plan.

Bela’s breakfast of instant potato.

A very steep and rough stretch of riding leads to the crest of the ridge in the morning.

Looking out from Brazos Ridge into the Cruces Basin Wilderness and Sangre de Christo mountains. These lands were the northern limit for the first Spanish explorers to forge north and until 1848 this region was all part of Mexico, along with much of the rest of the southwest.

Fun flowing riding on double and 4WD track through forest corridors made this memorable …

… and then golden grassy sections dotted with trees.

While the day’s topography led generally down, we still climbed over 1400 metres on the 97 km ride which ended well after dark. We caught sunset overlooking El Rito before coming off dirt onto pavement and rolling on to Vallecitos, where we camped in a wash (dry streambed) on the edge of the village.

Vallecitos was a thoroughly Hispanic village and for a moment in the morning I though we’d ridden right into Mexico by accident. It’s a town on the brink sadly, with a small population living among the crumbling adobe of once proud homes.

A community centre helps hold the fabric of this settlement together and we hung out there briefly in the morning, making use of the wifi and filling water bottles from the well.

Bela was done with cold nights and decided to take a detour that day to some hot pools to get some proper warmth in his bones. Anna, Hana and I would continue along the route proper over to the next village and through to Abiquiu.

We spent some time chatting with Arnold about the village’s struggles. I hope they can resolve their problems in this tiny pocket of Mexico in southwest USA.

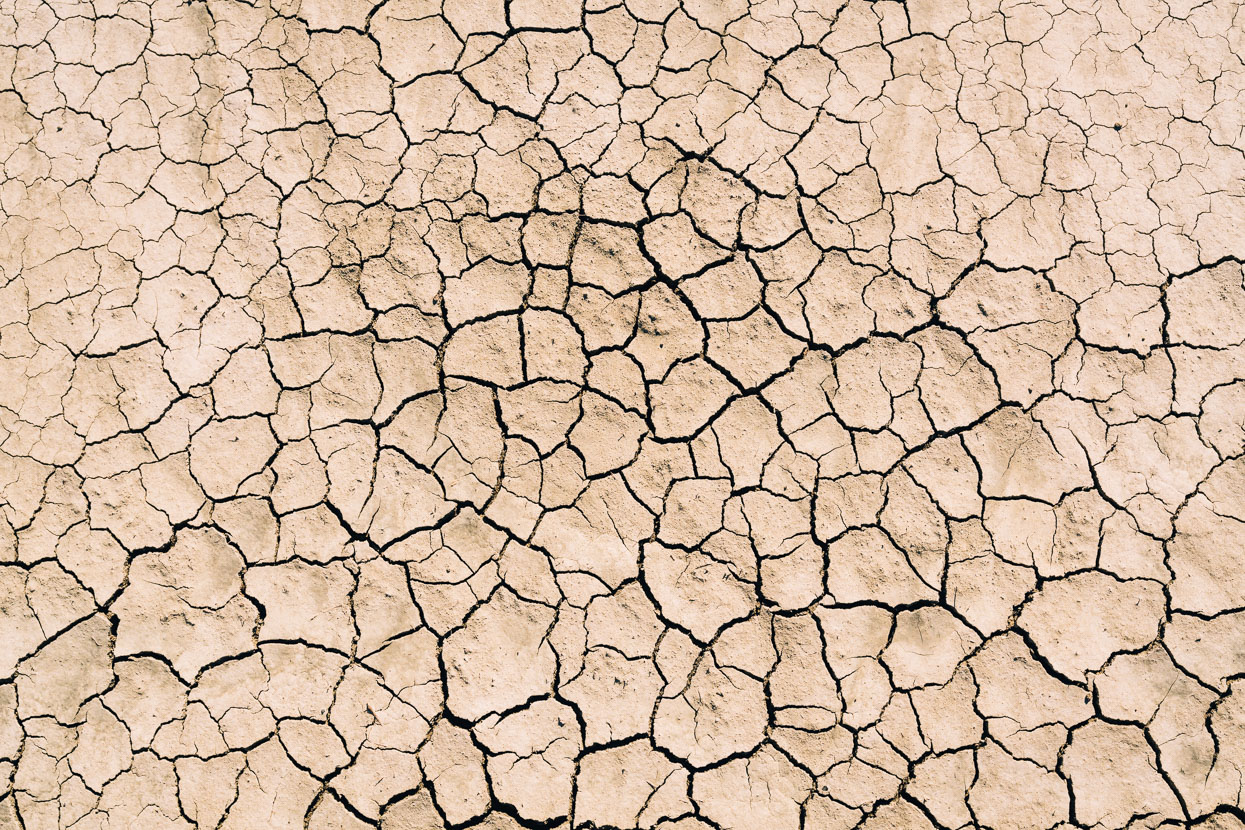

We left the village on a gradual ascent through pine forest and empty dirt roads, emerging after a long downhill into a totally different world: the forest on the edge of a much more open landscape covered with cactus, juniper and piñon. The air was warm and the soil dry as moon dust.

The ruins of the Santa Rosa de Lima church near Abiquiu, built 1734.

The cottonwoods were out in force, their colour in harmony with the reds of the surrounding hills. We caught a nice bit of light over Sierra Negra as evening came.

Abiquiu is well known as the chosen home for painter Georgia O’Keefe and as a small centre for peace, solitude and creativity. It was also the starting point for the Spanish Trail expeditions, which sought to open a trade route between the interior and coastal California. A small plaza, just above the general store and highway was the village’s former centre – arranged around the beautiful adobe St Thomas church.

The legendary Polvadera Mesa, a climb traversing a massive ancient caldera was next on the course, but heavy rain was due for the next day and a half. Roads here can be notoriously sticky and literally impassible during and after rain, so with this in mind we decided to detour around to Los Alamos, situated on the east side of the caldera and take a paved road which would still give us the views and experience of the mountain, without making a boring detour on the flat.

We left Abiquiu in dry conditions but ended up riding through a prolonged downpour heading up to Los Alamos. Sterile, orderly and so very ‘normal’ looking, Los Alamos was a change of scene for us. This town was the site of the top secret WWII Manhattan Project to create an atomic bomb. Formerly it had been a mesa-top recreation and camping area, but the urgency to create an atomic weapon soon turned this remote site into a small township and research base, covered with buildings. The actual test site, Trinity, was not too far away at White Sands. In fact it was remarkably only three weeks after the first successful test that the bombs (duplicates above) were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. These days Los Alamos is a thriving town serving hundreds of scientists working on atomic applications for both military and civilian purposes. We took a day off there to wait out the worst of the rain, which also brought snow to the hills above us.

The plaque reads: ‘This monument honours all those people gathered here at Los Alamos and drawn from its neighbouring communities whose work on the Manhattan Project produced the weapons that ended World War II and who later helped develop the nuclear forces that deterred global conflict for the past fifty years’.

The sense of local pride in the dubious ‘achievements’ of the Manhattan scientists was palpable and I was surprised (I probably shouldn’t be) at the view of history both locals and visitors are served. I’m of the school that dropping the bombs on an already shattered – and close to surrender – Japanese empire was totally unnecessary to end the war, and was nothing more than a last chance for the US to test its secret weapons and show the world the formidable power it now held.

Formidable power of another kind was unleashed when the greater Valles Caldera was formed in a series of eruptions 1.1 – 1.4 million years ago. A supervolcano, this 35km wide caldera contains a number of active vents, fumaroles and hot springs. Ongoing volcanic activity has shaped the caldera we see today, with the most recent eruptions being 50 – 60 thousand years ago, resulting in Rhyolitic features dotted all over the mountain such as cliffs, domes and canyons.

Our route over this caldera might have been a suitable option to avoid impassably muddy roads, but it certainly wasn’t an easy one: we climbed over 2000 metres over the 109km ride to Cuba.

About as good as road touring can be: awesome surrounds and a quiet, good quality road.

We even got a nice dirt section through a canyon and then open valleys late in the day before a massive (paved) descent off the mesa down to Cuba.

Cuba was another scrappy small town with a small grocery store and a couple of cafes and restaurants, along with a McDonalds. El Bruno’s Mexican restaurant is highly recommended!

The next section, a 2–3 day ride from Cuba to Grants, has roads that are also susceptible to becoming unrideable mud. We’d read that people had even been forced to abandon bikes on this section in the past, but with the storm passed we were looking at a great stretch of weather ahead so headed into it with confidence. As with previous days in southern Colorado and New Mexico, planning is required around water sources as surface water is increasingly scarce this far south. We left the highway about an hour out of Cuba and immediately rode into a whole new world.

To be lucky enough to experience this place by bike in fine weather felt like a privilege. Within a few minutes we saw our first tarantula, and our surroundings became increasingly mysterious and remote.

Mesas, canyons, arroyos and sagebrush. Like a mini Canyonlands.

Our map located well-water (the only we’d seen all day) just a short detour off the route, so we filled up and stopped a short time later, finding a perfect campsite on a high ridge, the valley and arroyos below sweeping away towards sandstone cliffs and ancient mesas.

Beautiful morning light along the edge of the San Luis Mesa. The previous day’s ride had passed the right hand peaks to the right and crossed the basin below.

Nopales and cholla are our new companions – no walking in bare feet around here. Especially as creatures unknown emerge from these mysterious holes at night.

Onwards through the desert, crossing arroyos riven by the last big rain storm. We can’t imagine being here in a downpour – it looks as if it would be hard to even walk, and water seems to pour everywhere. Even now, mud traps lay in the bottom of the deepest arroyos, sometimes swallowing our tyres a few inches.

Our next water stop was a rudimentary but functional well and solar powered pump supplying a nearby ranch. Fortunately the system wasn’t closed and we could access an outlet. When I turned the tap the contraption made some chugging noises, rattled violently and a burst of rusty looking water poured out at our feet. It finally cleared and we filled our bottles with it. Despite a strong sulphury smell it didn’t taste too bad.

Spotted a short distance from the road was this old structure. For animals or humans? We weren’t sure.

We didn’t rush this day. The weather was warm, the wind gently to our backs. Our tyres rolled easy over the dry dusty ground – the road’s contours providing a smooth and tactile ride. A perfect blue sky and soft wispy clouds set off the tone of our surroundings beautifully, everything in hard contrast and crisp with colour. As we circled the mesa features that seemed so distant would gradually draw close, their detail revealed or their true scale exposed. Landscape features changed constantly; always something waiting around the corner to capture our interest.

Feature of the day was the ‘Magic Mountain’ (Cerro Alensa 2458m), a prominent volcanic ‘neck’ left where hardened lava once filled the conduit of a volcano. Softer rock long since eroded away to reveal a much more slowly eroding core.

We pass a few ruins, this site an old ranch.

Cerro Alensa and Mesa Chivato behind.

A 700 metre (8km) climb right at the end of the day takes us high onto Mount Taylor, yet another ancient volcano within the San Mateo mountains. We arrive to find the spring dry and are thankful for the litres of water we carried up the climb just in case. Even as we stop the temperature is dropping fast and we’re soon wearing all the clothes we have and persevering to light a fire with scraps of damp wood. A small flask of cinnamon whiskey and some marshmallows also help soften the cold.

We’re long used to the frosts now, but cold mornings still bite sometimes – especially packing the bikes and taking down the tent.

Looking out from Mount Taylor to East Grants Ridge, Cibola National Forest.

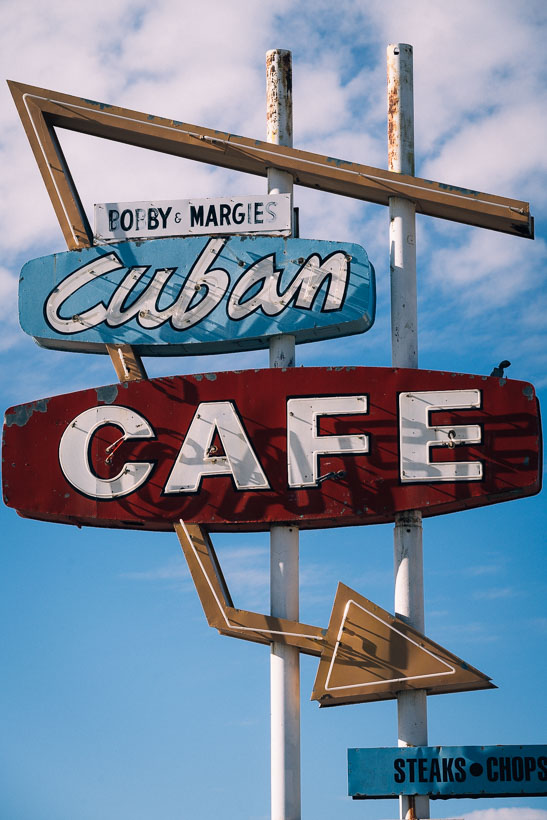

Route 66 passes through Grants. In its heyday the ‘Mother Road’ was a conduit to the west for tourists and travellers from the east, connecting towns, settlements and US culture inextricably. Locations along the route provided accommodation, food and their own brand of hospitality. Sadly, with the nearby interstate much of this culture is now gone, and like so many small towns we have visited on the Divide, Grants was looking more than a little jaded.

Replacing the character of old was a ‘new’ end of town, with the usual cookie cutter chain hotels and restaurants.

It was in Grants that we parted ways with Anna, having really enjoyed her energy and company for the past 17 days. For me and Hana about 10 days on the Great Divide route remained.

A lunch only a cycle tourist could eat.

Teddy bear cholla! Glad you guys appreciating NM, funky beautiful state and very culturally rich. Stunning photos as always. All the recent updates really making me miss the American West. Cheers for sharing! Bien viaje amigos!

Thanks Justin – loved it there!

Loving the Blog Mark n Hana. New Mexico landscapes put the ‘awe’ back into awesome. For an alternative view on the decision to drop ‘the Bomb’

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1946/12/if-the-atomic-bomb-had-not-been-used/376238/

You know, of all the Divide stories, blogs, photos, etc. that I have read/seen about the New Mexico section, this is the most documented and detailed. Some riders say it’s their favorite part, yet they neither say or show why; others only complain of being chased by dogs. You actually stopped and listened to the locals’ struggles and photographed their world. This is how it should be done. Thanks for sharing the story and the beautiful photos. I want to experience it for myself someday.

No chance you’ve been served a line about the history, I suppose? Just checking. I don’t know why you would be so sure of your version. Love the photos though.

Hi Diane, assuming you’re referring to Los Alamos? I’ve read quite a lot on the subject over the years – enough to form an opinion, which is all that is. I’m sure there are plenty of people who don’t agree with it. Glad you like the photos – are you riding the divide? We loved it.

cheers

Mark.